Insights on Management and Leadership

Introduction

This portfolio delves deep into management and leadership, addressing six crucial topics that leaders and managers encounter daily.

Firstly, it explores the classical and empiricist theories in management, contrasting traditional ideas with evidence-based practices.

Next, it examines motivational theories by Maslow and Vroom, shedding light on the factors that drive individuals to perform at their best in the workplace.

Moving on, the portfolio dissects various leadership styles, helping individuals identify whether they lean towards transformational or transactional leadership approaches.

Additionally, it discusses situational leadership theories proposed by Fiedler and Hersey-Blanchard, emphasizing the importance of leaders adapting their strategies to different contexts.

The leader-member exchange theory is also explored, highlighting the significance of the unique relationships between leaders and their team members and how they influence overall performance.

Lastly, the portfolio delves into business ethics, addressing the moral dilemmas leaders face and how they navigate corporate social responsibility in today’s customer-centric and competitive business landscape.

Classicist and Empiricist School of Management

Management theory has significantly evolved over time, thanks to the contributions of various researchers and experts (DuBrin, 2009). Peter Drucker, a renowned management guru, succinctly defined management as the act of providing direction, leadership, and making judicious decisions regarding resources (Drucker, 1994). Essentially, it involves achieving objectives while nurturing the development of individuals (DuBrin, 2009).

Two primary schools of thought dominate management theory: classicism and empiricism. Classicists emphasize what managers ought to do, whereas empiricists analyze what managers actually do (Holmes, 2012). According to DuBrin (2009), authentic management revolves around fostering the growth of individuals through their work rather than simply dictating orders.

Henry Fayol, often regarded as the father of management, played a pivotal role in classicism. He delineated five fundamental functions of management: planning, organizing, commanding, coordinating, and controlling (Morgen, 2003). However, some argue that Fayol’s approach is more suitable for small enterprises and may not adequately address the needs of larger, dynamic organizations (Morgen, 2003). Peter Drucker even suggested that Fayol’s principles should be considered alongside others rather than being relied upon exclusively (Drucker, 1994).

On the empiricist side, Henry Mintzberg emerged as a prominent figure. He advocated for breaking down management into distinct roles and responsibilities, asserting that experience serves as the best teacher (Mintzberg, 1994). Mintzberg classified organizational structures into five types and highlighted the multifaceted dimensions of managerial roles (Mintzberg, 1994).

Mintzberg’s research, which involved observing CEOs in action, revealed the myriad of complex challenges modern managers encounter (Mintzberg, 1994). Effectiveness, he argued, hinges on confronting issues directly while maintaining a holistic perspective (Holmes, 2012).

In conclusion, both Fayol and Mintzberg have significantly influenced management theory and practice, offering invaluable insights into how organizations can flourish in contemporary environments.

Content and Process Theories in Motivation

Employee motivation is now universally acknowledged as critical for organizational success. Gone are the days when constant supervision was thought necessary for employees to perform diligently. Today, managers concur that motivation is pivotal in extracting optimal performance from their teams (Gary & Christopher, 2006). Motivated employees demonstrate heightened commitment and productivity, directing their efforts towards achieving organizational objectives (King & Lawley, 2019).

Numerous psychological and behavioural experts, such as Maslow, McGregor, Herzberg, and Vroom, have contributed to motivation theory. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Vroom’s expectancy theory stand out as notable examples. Maslow posits that individuals are propelled to work by specific needs, progressing from basic necessities to higher-level growth aspirations (Maslow, 1954). Managers leverage rewards to incentivize employees to fulfil these needs progressively (Velnampy, 2007).

While Maslow’s hierarchy offers simplicity and insight into human behaviour, it faces criticism for overlooking cultural disparities and lacking empirical validation (McKee, 2014). Some argue that individuals can ascend the hierarchy without addressing lower-level needs first (King & Lawley, 2019; Velnampy, 2007).

In contrast, Vroom’s expectancy theory suggests that behaviour is steered by conscious choices to maximize pleasure and minimize pain (Vroom, 1964). Employees are motivated when they believe their efforts yield performance, leading to rewards that satisfy their needs (Gary & Christopher, 2006). Expectancy, valence, and instrumentality—belief in one’s capabilities, valuing outcomes, and trust in reward delivery—are central to this theory (King & Lawley, 2019).

For leaders and HR managers, comprehending employee motivations, providing requisite resources and training, and ensuring reward promises are fulfilled are imperative responsibilities (Josse & Robert, 2007). Nonetheless, critics contend that rewards may not always align with performance and can be influenced more by job skills and education (Velnampy, 2007). Moreover, quantifying effort, performance, and reward value poses challenges.

Despite ongoing debates, motivation remains indispensable for organizational productivity. Modern organizations employ diverse motivational theories, tailoring them to suit their specific requirements to enhance employee performance and satisfaction.

Transformational and Transactional Leadership

High-quality leadership stands as a cornerstone in modern businesses, encompassing goal-setting, vision provision, ethical stewardship, and employee motivation (Daniel, 2018). The fate of organizations often pivots on leadership prowess (Gardner et al., 2010).

Leadership research has birthed various theories, including the Great Man and Traits theories, contingency and situational leadership theories, and transformational and transactional leadership (Goleman, 2002). Here, our focus narrows to the latter two.

Transactional leadership, outlined by Max Weber in 1947, is prevalent in short-term planning and control (Carter, 2008). It entails directing and motivating employees through the mechanism of rewards and punishments (Goleman, 2002). Subordinates receive rewards for compliance and face punishment for non-compliance (Gardner et al., 2010). While effective in straightforward settings, it faces criticism for objectifying employees and lacking adaptability in complex scenarios (Prentice, 2004).

Transformational leadership centres on inspiring and motivating employees toward innovation and change (Northouse, 2015). Leaders utilize idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individual consideration to forge connections with employees (Pendleton & Furnham, 2012). Extensive communication, ethical emphasis, and encouragement of selflessness characterize this approach (Northouse, 2015).

Effective transformational leadership fosters enthusiasm, loyalty, and commitment, thereby driving organizational success (Gold et al., 2010). However, leaders must steer clear of negative outcomes and ensure alignment with employees’ perspectives (Carter, 2008; Pendleton & Furnham, 2012). Exemplars of successful transformational leadership include figures like Steve Jobs and Richard Branson.

Situational Leadership Theories

Situational leadership, a rising trend in recent times, revolves around tailoring leadership styles to suit the current needs (Thompson & Vecchio, 2009). Northouse (2015) outlines four styles within this approach: directing, coaching, facilitating/participating, and delegating/empowering.

Directing prioritizes immediate goals, while coaching entails a high focus on both tasks and relationships, encouraging discussions on task importance and execution (Prentice, 2004). Participative leadership allows followers to take the lead, emphasizing relationships over tasks (Hackman & Craig, 2009). Delegating and empowering also involves empowering followers, thereby enhancing motivation and commitment (Thompson & Vecchio, 2009).

Fiedler (1971) and Hershey and Blanchard (1977) have significantly influenced situational leadership theory. Fiedler’s model considers both leadership style and situational favourableness, assessed through the LPC scale and task structure, among other factors (Prentice, 2004). While appreciated for its structured approach, it’s criticized for its lack of flexibility (Carter, 2008).

Hershey and Blanchard (1977) emphasize adapting leadership styles based on follower readiness and commitment (Prentice, 2004). Although their model is straightforward, it’s deemed subjective and rigid.

Despite a scarcity of robust empirical evidence, situational leadership advocates for leaders to adjust their style based on the situation and follower competence and commitment.

Leader-Member Exchange Theory

This segment of the portfolio delves into the Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory, which underscores how leaders cultivate relationships with their team members, emphasizing soft skills, empowerment, and motivation over mere rewards and punishments. Originating in the 1970s by Graen and Cashman (1975), the theory has evolved to underscore the significance of manager-team relationships.

As per LMX theory, there are three stages in the manager-team member relationship: role-taking, role-making, and routinization (Hiller & Day, 2003). Initially, in role-taking, new team members join, and managers evaluate their capabilities. Subsequently, in role-making, members engage in tasks, and managers determine the “in-group” based on loyalty and trust, relegating others to the “out-group.” Finally, in routinization, routines are established, with greater emphasis on the in-group, resulting in disparate treatment between in-group and out-group members (Ilies et al., 2007).

While lauded for its simplicity and adaptability, LMX theory has encountered criticism for fostering inequality and offering vague guidelines for in-group inclusion (Harris et al., 2011). Moreover, its application can be challenging if leaders adhere rigidly to their viewpoints and resist adaptability.

Despite its limitations, LMX theory finds support in research regarding its positive impact on organizational outcomes (Harris et al., 2011). Nonetheless, it’s imperative for leaders to foster strong relationships with all team members, not solely those in the in-group, and to tailor their behaviour accordingly based on the unique dynamics of each relationship.

Deontological and Corporate Ethics and Association with Corporate Social Responsibility

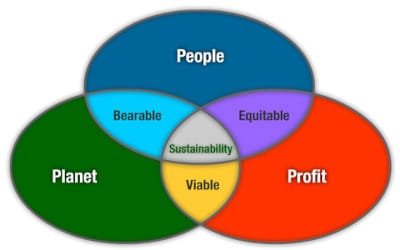

In recent years, the surge in various scams, particularly financial ones, has brought corporate governance and ethics into sharp focus. Carroll’s (1991) model of corporate social responsibility underscores that companies should not merely comply with the law but should also strive to exceed ethical standards.

With organizations navigating multiple stakeholders, leaders and managers must grasp ethical theories and codes of conduct (Carroll & Buchholtz, 2015). However, ethics proves to be a challenging subject, often presenting significant dilemmas for managers (Crane & Matten, 2016).

Let’s dissect two ethical theories: deontology and consequentialism. Deontology posits that actions are evaluated based on predefined sets of rules. It emphasizes adherence to these rules; ethical actions align with them, whereas deviations are deemed unethical (De George, 1999). Think of it as Kant’s notion of duty-bound ethics, where certain acts are considered morally obligatory, regardless of their consequences (Crane & Matten, 2016).

Deontology stresses fairness, consistency, and equal treatment for all. While straightforward, it suffers from drawbacks. When moral duties conflict, there’s no clear resolution, and it lacks flexibility, offering no room for ambiguity (De George, 1999; Salvador & Folger, 2009).

Moving on to consequentialism, which asserts that the consequences of actions determine their morality. It encompasses ethical egoism, group consequentialism, and utilitarianism (De George, 1999).

Consequentialism offers benefits; it demystifies ethics, provides a practical approach to resolving moral dilemmas, and encourages altruism. Moreover, it prioritizes what’s best for humanity over blind adherence to rules (Hinman, 2012; Stables, 2016).

However, critics argue that consequentialism lacks a moral foundation, making it challenging to discern between good and evil. It can even justify heinous acts and struggles to explain why certain actions are wrong when they seem obviously so (Seidel, 2018; Stables, 2016).

For managers, grappling with ethical decisions is a genuine struggle. Choosing between deontology and consequentialism isn’t straightforward, but comprehending these theories can aid them in navigating ethical quandaries (Hinman, 2012). It’s about striking the right balance and making decisions that align with ethical principles.

Conclusions

This portfolio delves into crucial organizational, management, and leadership topics, spanning classicist and empiricist management schools, motivation theories like Maslow’s and Vroom’s, and leadership styles such as transformational and transactional leadership. Additionally, it explores situational leadership theory, the leader-member exchange theory, and ethical theories like deontology and consequentialism.

These topics hold particular significance for marketing managers. Why? Because they must apply ethical principles in the market to ensure customers aren’t adversely affected. Moreover, as many marketing managers oversee large teams, comprehending various leadership theories is essential for effectively guiding their squads. Motivating team members is another pivotal aspect of their role, making knowledge of motivational theories invaluable in boosting morale and productivity.

References

Ashkanasy, N. M., & O’Conner, C. (1997). Value congruence in leader-member exchange. Journal of Social Psychology, 137(5), 647–662.

Bauer, T. N., & Green, S. G. (1994). Effect of newcomer involvement in work-related activities: A longitudinal study of socialization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(2), 211-23.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48.

Carroll, A. B., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2015). Business and society: Ethics, sustainability and stakeholder management (9th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Carter, M. N. (2008). Overview of Leadership in Organizations. London: Routledge.

Craft, J. L. (2013). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 221–259.

Crane, A., & Matten, D. (2016). Business Ethics (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Daniel, G. (2018). What Makes a Leader? In Contemporary issues in leadership (pp. 21-35). London: Routledge.

De George, R. T. (1999). Business ethics (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Drucker, P. (1994). “The theory of business”. Harvard Business Review, 72(5), 95-104.

DuBrin, A. J. (2009). Essentials of management (8th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson Business & Economics.

Fiedler, F. E. (1971). Leadership. New York: General Learning Press.

Gardner, W. L., Lowe, K. B., Moss, T. W., Mahoney, K. T., & Cogliser, C. C. (2010). Scholarly leadership of the study of leadership: A review of the leadership quarterly’s second decade, 2000–2009. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 922–958.

Gary, P. L., & Christopher, T. E. (2006). Keys to motivating tomorrow’s workforce. Human Resource Management Review, 16(1), 181–198.

Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1997). Meta-Analytic Review of Leader-Member Exchange Theory: Correlates and Construct Issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 827-844.

Gold, J., Thorpe, R., & Mumford, A. (2010). Leadership and Management Development. London: Kogan Page.

Goleman, D. (2002). Leadership That Gets Results. Harvard: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation.

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Balkin, D. B., & Cardy, R. L. (2008). Management: People, Performance, Change (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Graen, G. B., & Cashman, J. (1975). A role making model of leadership in formal organizations: A developmental approach. In J. G. Hunt, & L. L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership frontiers (pp. 1201-1245). Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press.

Graen, G. (1976). Role-making processes within complex organizations. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1201-1245). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Hackman, J., & Craig, M. (2009). Leadership: A Communication Perspective. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Harris, K. J., Wheeler, A. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (2011). The mediating role of organizational job embeddedness in the LMX–outcomes relationships. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(2), 271–281.

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1977). Management of Organizational Behavior – Utilizing Human Resources. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Herzberg, F. (1959). The Motivation To Work. New York: Wiley.

Hiller, J. N., & Day, D. V. (2003). LMX and Teamwork: The Challenges and Opportunities of Diversity. In LMX Leadership: The Series (pp. 29-57). Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Hinman, L. M. (2012). Contemporary Moral Issues: Diversity and Consensus (4th ed.). London: Routledge.

Holmes, L. (2012). The Dominance of Management: A Participatory Critique: Voices in Development Management. London: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Ilies, R., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Leader–Member Exchange and Citizenship Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 269-277.

Josse, D., & Robert, D. (2007). Signaling and screening of workers’ motivation. Journal of Economic Behaviour & Organization, 62(1), 605–624.

King, D., & Lawley, S. (2019). Organizational Behaviour. Oxford: OUP.

Kotler, P., & Armstrong, G. (2018). Principles of Marketing (17th ed.). New Jersey: Hoboken.

Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper.

McGregor, D. (1960). The Human Side of Enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.

McKee, A. (2014). Management: A Focus on Leaders. Boston: Pearson.

Mintzberg, H. (1994). Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Morgen, W. (2003). Fifty key figures in management. London: Routledge.

Northouse, P. G. (2015). Leadership: Theory and Practice (7th ed.). London: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Pendleton, P., & Furnham, A. (2012). Leadership: All you need to know. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Prentice, W. C. H. (2004). Understanding Leadership. Harvard: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation.

Salvador, R., & Folger, R. G. (2009). Business ethics and the brain. Business Ethics Quarterly, 19(1), 1–31.

Seidel, C. (2018). Consequentialism: New Directions, New Problems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stables, A. (2016). Responsibility beyond rationality: The case for rhizomatic consequentialism. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, 9(2), 219–225.

Thompson, G., & Vecchio, R. P. (2009). Situational leadership theory: A test of three versions. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(5), 837–848.

Velnampy, T. (2007). Factors Influencing Motivation: An Empirical Study of Few Selected Sri-Lankan Organizations. London: Researchgate.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and Motivation. New York: John Wiley and Son.

Wood, J. C., & Wood, M. C. (2002). Henri Fayol: Critical Evaluations in Business and Management. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Wren, D. A. (2001). Henri Fayol as a strategist: a nineteenth century corporate turnaround. Management Decision, 39(6), 475–487.

More From This Category

Inclusion of Networking for Women and Minority Group Members in the Workplace

Modern businesses continue to be dominated by men of the majority community, despite increasing entry of women and members of minority groups. Research has revealed that members of this group tend to, both intentionally and unintentionally interact with people of their own groups on account of homophilous reasons, thereby excluding access to women and members of ethnic minorities.

This results in considerable disadvantages for the excluded groups because network occurrences and dynamics often result in formal decisions for promotions, inclusion in new projects and giving of new responsibilities.

Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is truly one of the most puzzling aspects of today’s business world (Visser, 2008). It’s evolving rapidly, appearing to be both complex and yet somewhat unclear (Visser, 2008). Despite efforts from academic experts and management practitioners to define CSR, there’s still no universally accepted definition (Visser, 2008). The World Business Council for Sustainable Development takes a stab at it, defining CSR as: “the ethical behaviour of a company toward society; management acting responsibly in its relationship with other stakeholders who have a legitimate interest in the business. It’s the commitment by business to act ethically, contribute to economic development, and improve the quality of life of the workforce, their families, and the local community and society at large.” (Petcu et al., 2009, p. 4)

Globalisation Challenges

Globalisation is the tendency of the public and economies to move towards greater economic, cultural, political, and technological interdependence. It is a phenomenon that is characterised by denationalisation, (the lessening of relevance of national boundaries) and is different from internationalisation, (entities cooperating across national boundaries). The greater interdependence caused by globalisation is resulting in an increasingly freer flow of goods, services, money, people, and ideas across national borders.

0 Comments