Regulation Analysis: Examination and Analysis of Regulation in Business

Published in 2021

Introduction

Statutory regulation is becoming more necessary because self-regulation is associated with the creation of environments that are favourable for the suppression of competition and for the construction of cartels. Self-regulation often proves to be inadequate because of the lack of jurisdiction of exchanges over individuals and organisations, who are not their members, as also by their lack of criminal authority

Statutory Regulation V Self-Regulation

Governments, along with international institutions like the IMF and the World Bank and regulatory agencies like the SEC in the US, the FSA in the UK and the JFSC in Jersey are working towards improvement of the quality of financial systems and the construction of regulatory systems that are grounded in equity and transparency and which further the principles of upholding the integrity of markets and protection of investors.

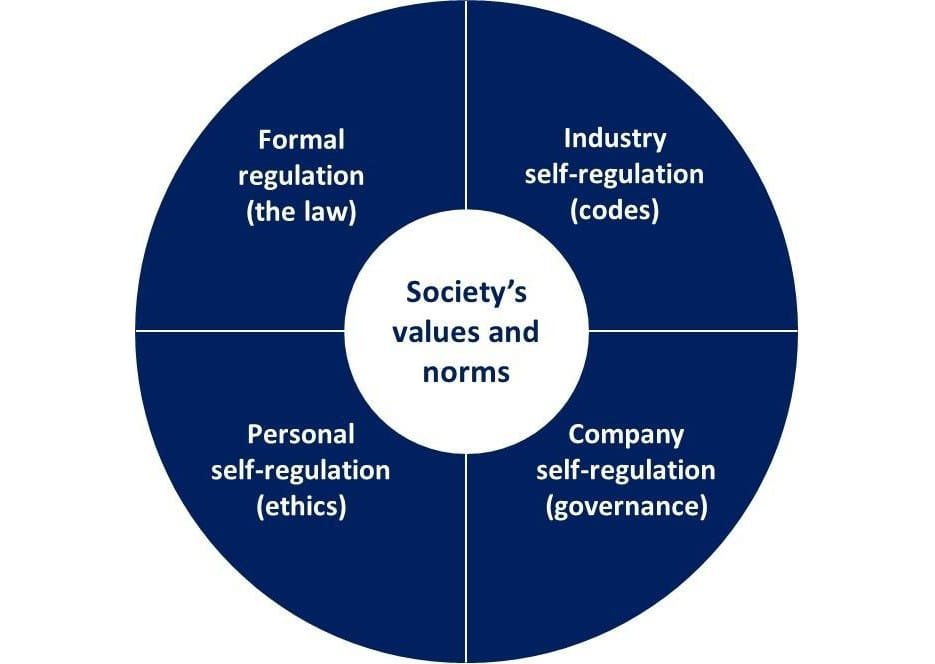

Regulation of financial markets is usually either statutory, or self, or as is most common, a deliberate mix of statutory and self-regulation. Statutory regulation refers to regulation that is determined and implemented by statutory bodies that are controlled by national governments, whereas self-regulation represents regulatory practice that is formulated, developed and implemented by market participants or exchanges.

Neo-liberal economics has always stood for minimal statutory interference and a dominant role for self-regulatory systems; the constant occurrence of financial scandals and engagement in misdemeanours by market participants have however led to an ever increasing incidence of statutory regulation.

Whilst statutory regulators are limited by asymmetry of information, high costs and less than adequate requirements for disclosure, their apparent need for protection of depositors, the achievement of monetary stability and the prevention of collapse of payment system are leading to continual increases in their role in regulation of financial services

Statutory regulation is becoming more necessary because self-regulation is associated with the creation of environments that are favourable for the suppression of competition and for the construction of cartels. Self-regulation often proves to be inadequate because of the lack of jurisdiction of exchanges over individuals and organisations, who are not their members, as also by their lack of criminal authority. There can be instances of such individuals participating in or encouraging misconduct in the form of fraud or insider trading, but who cannot be tackled effectively by exchanges. Apart from such issues, exchanges can also be hampered by conflict of interest, even as some participants can apply inappropriate pressure on their working.

Rules and Principles Based Regulation

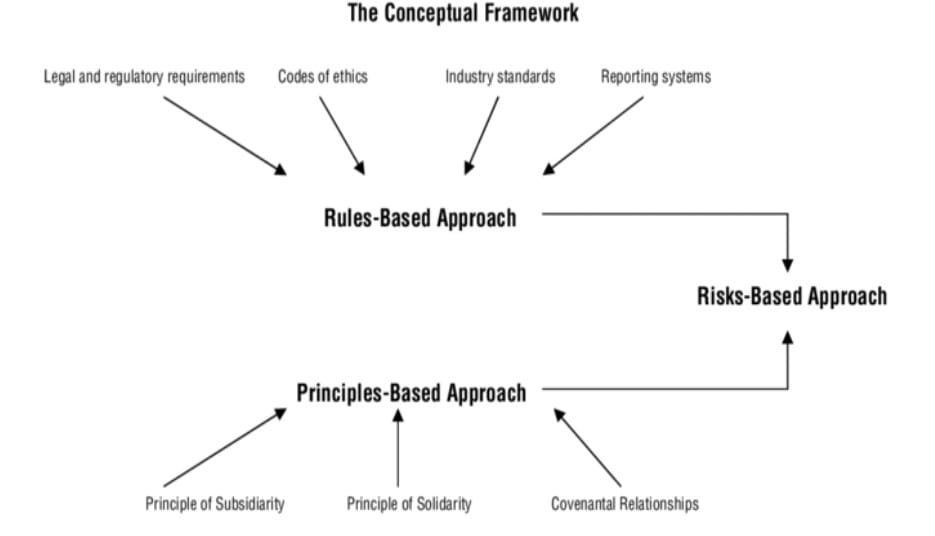

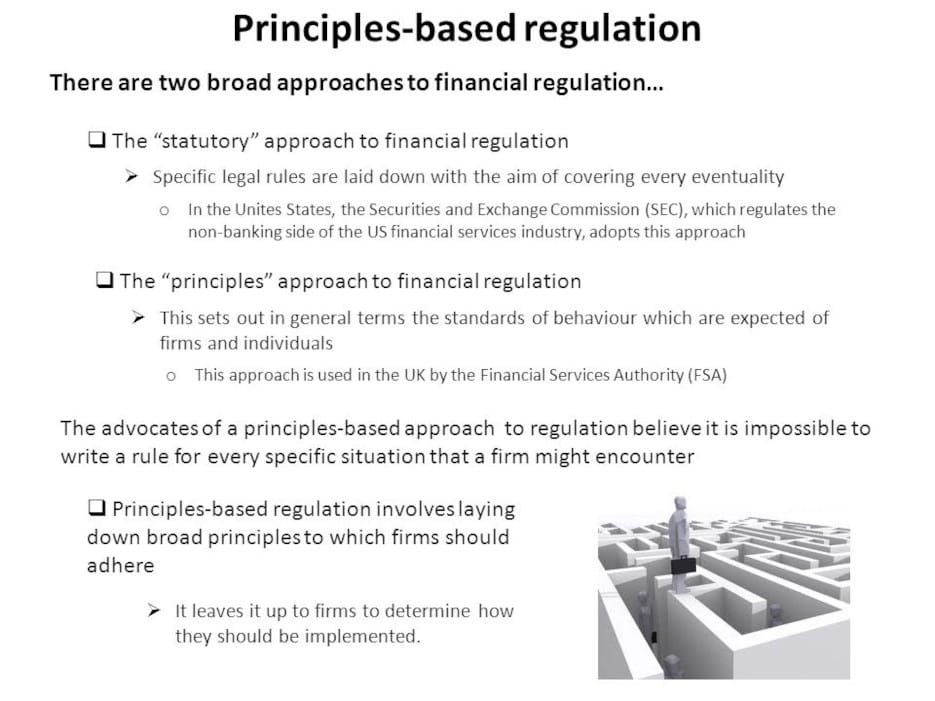

Regulatory actions are by and large segregated into two clear areas, namely rule based regulation and principles based regulation.

Rules based regulation represents, as the name implies, a regulatory system that is constructed on the basis of articulated rules that are extremely specific and do not by and large allow for interpretation. Such rules based regulations have been followed with great enthusiasm in the past, especially in the United States, because of the conviction of regulators that markets function best in an environment of rigid rules for the governing of actions of market participants.

Principles based regulations are however coming into sharp focus as the answer to the cumbersome, bureaucratic, and unwieldy environment that is often created by over enthusiastic and blind implementation of rules without assessment of the actual objectives of regulation. Principles based regulation represents a regulatory system that eschews the liberal use of rules and focuses on specific principles like the protection of market integrity, the safeguarding of the right of clients and transparency in dealings.4 Such a regulatory approach allows managements to focus on the principles that need to be maintained and the outcomes that such principles aim to achieve, rather than on meeting numerous rules, many of which may be impractical, outdated and obstructive of business efficiency.

Enforcement Action by Regulators against Organisations

Financial regulators by and large attempt to follow two key principles, namely (a) the promotion of efficient, orderly and equitable markets and (b) the provisioning of assistance to retail customers in order to allow them to obtain a fair deal. Regulatory bodies have wide ranging powers to create and enforce rules, as also to execute investigations, to achieve the objectives of regulation of financial services.

Regulators in the normal course of their work take steps to assess the activities of firms and ascertain whether their activities, those that have already occurred and those that can occur in future, can lead to cause undermining of public confidence in markets, reduction of public awareness, harm to consumers and financial crime. Regulators are charged with preventing activities that can pose risks to existing financial systems. They are also responsible for the promotion of transparency and efficiency in the working of financial markets and for the prevention of market abuses like fraud, insider trading and market manipulation.

Regulators can take action when they feel that the actions of firms in the financial services sector can lead to or have caused the disturbance of such objectives.

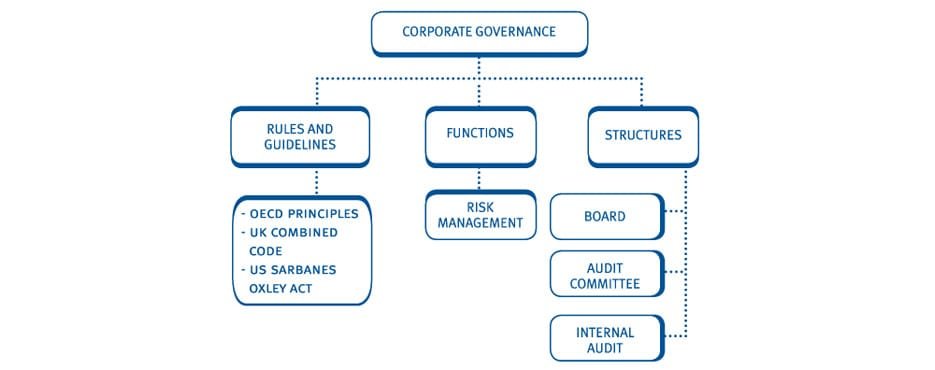

Role of Corporate Governance in Regulation of Financial Services

Corporate governance in the financial services sector differs significantly from that in other sectors of the economy, because of the significantly greater risks that banks and other entities in the sector can pose to the overall economy. Organisations in this sector, if badly managed, can well fail in meeting counter party obligations to other institutions and consequently affect the provisioning of liquidity to other economic sectors. Whilst regulators impose stricter standards and rules on managements and banks and other financial institutions than on organisations in non-financial sectors, the role of corporate governance becomes critical for the maintenance of such rules, as well as in the balancing of the interests of shareholders, creditors and depositors.

Regulation of institutions in the financial services sector is a complex task because of the international nature of the business and the use of various sophisticated and increasingly complex financial instruments that are being increasingly adopted in the industry. The development of complex strategies for risk management, whilst allowing for improvement of profits, can generate greater risks and increase the probability of liquidity problems.5 The premium placed by managements on earning profits for share holders, along with the limited liability structure of such organisations, often encourages managements of organisations in the sector to undertake risky ventures.

Appropriate corporate governance for organisations in the sector require the institutionalisation of internal control systems to control agency problems, which can arise out of managements having different risk preferences from other stake holders, as well as for addressing the asymmetries of information that can arise from such situations. Whilst the corporate governance function is basically the responsibility of the board of directors, it needs to be recognised that senior managers also play an integral role in the process and that they should specifically assume the role of overseeing the actions of line managers in specific business areas.

The audit process is an integral portion of the corporate governance process and auditors should have the necessary authority to bring all their apprehensions and discomfort with regard to operations to the notice of the board of directors.

The board should ensure clarity in the organisational structure of such financial services organisations; such structures should have clearly identified communication lines and decision making responsibilities.

Transactions with related parties and affluence should be itemised and their extent be clearly visible.5 Corporate governance also calls for all organisations in the sector to constantly work on internal controls, operational systems and risk management practices, such that information on risks exposure is continuously made available and can be acted upon.

Three Examples of Corporate Governance

Corporate governance is essentially a vast area and dependent both upon rules and regulations imposed by statutory regulators, as well as upon measures taken by the board of directors to ensure the protection of the interests of shareholders and other stake holders like clients, depositors and creditors.

Three different examples of corporate governance that are different in nature but important for the functioning of organisations are (a) the elaboration of responsibilities of the senior management, (b) the adoption of risk management measures and (c) the ensuring of statutory requirements.

The senior managements of financial services organisations play critical roles that are influenced by the principle-agent relationship and by opposing pressures between actions that aim at profitability and measures that are required for risk control. The elaboration of senior management responsibilities (and their reporting lines), both vertical and horizontal, are important for the construction of good corporate governance systems.

Whilst non-compliance with the meeting of statutory requirements could well lead to the imposition of severe penalties upon such organisations, the formulation and development of strong risk control procedures can help organisations from failure and collapse.

Outcomes for Principle based Regulations

Principle based regulation is now moving to the core of the regulatory agenda.1

Whilst principles have been important for the regulation of financial services for quite some time, the increasing stress on principles based regulation by regulatory authorities is causing a radical shift in the nature of the regulatory process.

The main outcome of shifting to a regulatory structure that is based more on principles and less on rules is to improve the behaviour of both firms and customers, even whilst providing managements of firms with greater flexibility to manage their operations and control their risks. Such regulatory systems aim to (a) provide firms with greater flexibility in operations, (b) improve competence and quality of service, (c) ensure integrity in functioning, and (d) ensure that customers are treated with care and fairness.

Detailed rules have a number of limitations and have not always been successful in delivering the outcomes they were expected to achieve. Rules cannot be expected to cover all sorts of circumstances. They focus on processes rather than outcomes, become detailed and obsolete, are not followed by some firms, and are known to restrict innovation and inherit competition.

The adoption of principles should lead to imaginative approaches to the meeting of minimum requirements. The adoption of principles will essentially provide senior managements with far greater flexibility in carrying out their responsibilities and encourage them to think about different parts of their business, and whether their processes meet the needs of customers.

The relationship between firms and regulatory authorities will change both in content and in level of interaction. Whilst compliance in the past was mostly handled by specialists, the change to principles will lead to discussion of broader and more relevant issues. The reasons for enforcement action will also alter significantly, with there being view lesser action for non- compliance of rules and more for breach of principles.

A key outcome of the principles based approach is the requirement for firms to treat customers fairly. It has been found time and again that some firms often do not take adequate care to ensure fair treatment for their customers. Focussing on principles will enable highlighting of areas where customers can be rendered vulnerable to treatment that is not fair, encourage firms to take efforts to ensure fair treatment of customers, and to the underlining of responsibilities of senior managements in the delivery of fair treatment to customers. The need to deliver fair treatment to customers should lead to changes in corporate cultures of firms, improvement of training and competence infrastructures, and identification of good and poor practice.

References

Adams, R, & Mehran, H, (2003), Is Corporate Governance Different for Bank Holding Companies, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review 123-141

Baldwin, R, Hutter, B &Rothstein, H, (2009), Risk regulation, Management and compliance, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk/Documents/Risk%20regulation%20report.pdf

Barth, J, R, Caprio, G, & Levine, R, (2008), Bank Regulations Are Changing: For Better or Worse?, Comparative Economic Studies, 50(4), 537

Bhattacharya, U, Neal, G, & Bruce H, (2006), The Home Court Advantage in International, Corporate Litigation, Working Paper, Indiana University

Birks, P, (1995), Laundering and Tracing, Oxford: Oxford University

Brad, B & Odean, T, (2000), Trading is Hazardous to Your Wealth, The Common Stock

Investment Performance of Individual Investors, Journal of Finance 55, pp 773-806

Briault, C, (2007), Principles-based regulation in the retail market, FSA, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from,www.fsa.gov.uk/pages/Library/Communication/…/0423_cb.shtml

Britton, R, (2009), The role of self-regulation in the global market place, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, www.anbid.com.br/auto_regulacao…/Richard_Britton_1011.pdf

Bortolotti, B, & Fiorentini, G, (1999), Organized Interests and Self-Regulation, An Economic Approach). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Cioffi, J, W, (2003), Expansive Retrenchment: The Regulatory Politics of Corporate Governance Reform and the Foundations of Finance Capitalism, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, ies.berkeley.edu/research/files/SAS04/SAS04-Mechanisms_Regulation.pdf

Christopher, H, Rothstein, H, & Baldwin, R, (2004), The Government of Risk, Understanding Risk Regulation Regimes, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Chorafas, D, N, (2000), New Regulation of the Financial Industry, Basingstoke, England, Macmillan

Emerging, Anti-Money Laundering, Risks to Financial, Institutions, (2007), Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, www.risk.lexisnexis.com/whitepapers

Fleishman, H, & Claire S, (2009), Financial Services Industry Hit Hardest by Fraud According to Global Report, 202-828-9767, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from,

http://news.moneycentral.msn.com/ticker/article.aspx?Feed=BW&Date=20091019&ID=10525512&Symbol=MMC

Financial Services Authority, (1999), A cost-benefit analysis, of statutory regulation

of mortgage advice, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/policy/P26.pdf

Fighting Fraud within Financial Services: A New Era of Financial Crime and Compliance Management, (2009), Retrieved January 11, 2010 from www.oracle.com/industries/financial_services/pdfs/fighting-fraud-wp.pdf

Finnegan, L, (1999), Sustainable Development. Occupational Hazards, 61, pp,54

Goetzmann, W, N, & Kumar, A, (2005), Why Do Individual Investors Hold Under-Diversi_ed, Portfolios, Yale University

Goodhart, C, (2001), Regulating the regulators, Accountability and Control, Paper Financial Markets Group, London School of Economics 7-9

Grinblatt, M, & Matti, K, (2001), How Distance, Language, and Culture Influence Stockholdings, and Trades, Journal of Finance 56, pp 1053-1073

Howard, S, (2005), Investment funds in the Channel Islands, competition rekindled, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, www.howard.je/pdf/investment_fund_categories_in_jersey.pdf

Howells, P, & Bain, K, (2007), Financial Markets and Institutions, 5th ed. New York: FT Prentice Hall

Hong, H, Kubik, J, D, & Jeremy C, S, (2004), Social Interaction and Stock Market Participation, Journal of Finance 59, pp 137-163

Hutter, B, M, (1997), Compliance, Regulation and Environment,. Oxford, Oxford University

Jersey Financial Services Commission, (2009), Retrieved January 11, 2010 from http://www.jerseyfsc.org/

Jonathan, W, (2002), The Supervisory Approach, ‘Basel II and Developing Countries’ CERF Working Paper no, 4

Jones, I, & Pollitt, M, (2003), Understanding How Issues in Corporate Governance Develop, Cadbury Report to Higgs Review, ESRC Centre for Business Research, (Judge Institute, University of Cambridge, pp. 14-15.

Kenneth, A, & Hayong, Y, (2005), Matching Bankruptcy Laws to Legal Environments, Working, Paper, Columbia University

Kondo, J, E, (2006), Self-Regulation and Enforcement in Financial Markets, Evidence

From Investor-Broker Disputes at the NASD, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, web.mit.edu/jekondo/www/jobmkt_paper.pdf

Kloos, B, Alter, J, & Stone, M, (2006) Securities Fraud, American Criminal Law Review, 43(2), 921

Kuhnen, Camelia, M, (2006), Social Networks, Corporate Governance and Contracting in the Mutual Fund, Industry, Northwestern University

Lightle, S, S, Baker, B, & Castellano, J, F, (2009), The Role of Boards of Directors in Shaping Organizational Culture. The CPA Journal, 79, 68

Mall, M, (2007), Derailing the Gravy Train, A Three-Pronged Approach to End Fraud in Mass Tort Medical Diagnosing, William and Mary Law Review, 48(5), 2043

McCrudden, C, (1999), Regulation and Deregulation: Policy and Practice in the Utilities and Financial Services Industries, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Mayer, B, (2008), Financial Services Regulatory & Enforcement, Global Financial Markets Initiative, Tax Transactions update, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, www.mayerbrown.com/publications/index.asp?page=40…Y

Mills, A, (2008), Essential Strategies for Financial Services Compliance, Chichester, UK

Morgan, G, & Engwall, L, (1999), Regulation and Organizations, International Perspectives, London: Routledge

Moore Stephens, (2009), A MOORE STEPHENS GUIDE TO FINANCIAL SERVICES (JERSEY) LAW 1998, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from www.moorestephens-jersey.com/…/AMooreStephensGuidetoFinancialServices(Jersey)Law1998.pdf

Nick, M, (2009), Jersey beats UK on financial regulation, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, www.guardian.co.uk/…/jersey-beats-uk-financial-regulation

Ostrosky, J, A, Leinicke, L, M, Digenan, J, & Rexroad, W, M, (2009), Assessing Elements of Corporate Governance, a Suggested Approach. The CPA Journal, 79, 70

Peter A, H, & Soskice,D, (2001), An Introduction to Varieties of Capitalism, in Hall, Peter A. and David Soskice, eds., Varieties of Capitalism, The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Pires, R, (2008), Promoting Sustainable Compliance, Styles of Labour Inspection and Compliance Outcomes in Brazil, International Labour Review, 147(2-3), 199

Power, M, (2003), The Invention of Operational Risk, ESRC Centre for Analysis of Risk and Regulation, London School of Economics

Roseman, E, & Henning, B, (2009), Regulatory and Litigation Support Services, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, www.icfi.com/Services/Regulatory_Support/doc…/litigation-reg-support.pdf

Stiglitz, J, E, (1989), Principal and agent in J. Eatwell, M, Milgate & P, Newman, Allocation, Information and Markets The New Palgrave

Simon H. S, (2003), The financial services commission- A case for reform, The Jersey Law Review – Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, www.jerseylaw.je/…/jerseylawreview/feb03/JLR0302_Howard.aspx

Stessens, G, (2000), Money Laundering, Pinochet, the Junta, and A New International Law Enforcement Model, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

Strongin, D, (2002), Promoting fair and transparent regulation, 212/618-0513, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from www.dstrongin@sia.com

Terry, B, (2003), High-level debate on corporate governance and financial market reform, European Financial Services Regulation Issue 8, pp. 1-2

Teuten, P, (2007), Regulation, It’s the Principle of the Thing, Risk Management, 54, 34

Vincelette, R, (2002), Risk Managers Tap the Reinsurance Market, Risk Management, 49, 10

Wiley, J & Briault, C, (2007), Principles-based regulation in the retail market, Retrieved January 11, 2010 from, www.fsa.gov.uk/pages/Library/Communication/…/0423_cb.shtml

More From This Category

Does Capital Structure Matter

The capital structure of a modern corporation is, at its rudimentary level, determined by the organisational need for long-term funds and its satisfaction through two specific long-term capital sources, i.e. shareholder-provided equity and long-term debt from diverse external agencies (Damodaran, 2004). These sources, with specific regard to joint stock companies, retain their identity but assume different shapes.

An Introduction to Keynesian Economics

John Keynes (1883-1946) and his followers developed a school of economic tho0ught that led to a paradigm shift in economics, replacing the study of the economic behaviour of companies and individuals, i.e. microeconomics, with the investigation of the behaviour of the economy in totality, namely macroeconomics.

Standard Costing and Variance Analysis

The widespread acceptance of standard costing for a sustained period of time provides a categorical endorsement of its suitability for the standardised mass production based manufacturing activity that was characteristic of western businesses for much of the 20th century.

Causes and Effects of the 2008 Recession

Increasing defaults led to the bankruptcy of many mortgage lenders. The banks and financial institutions that had purchased the mortgage debt from such mortgage companies were also affected badly and had to write-off large scale losses. Such losses were not restricted to the banks in the United States but occurred across banks and financial institutions in the UK and other countries in Europe. A number of banks faced severe credit problems and needed to borrow money from other banks. During this period it became very difficult for banks to gauge the financial health of other companies in the sector. Bank and institutional failures kept occurring sporadically, sometimes occurring after intervals of a few months; each such gap belying people into believing that the worst was over.

What is the difference between Orthodox and Heterodox Economics?

This paper delves into the similarities and differences on the role of money in the heterodox and orthodox economic frameworks. Traditionally literature on economics, both at the introductory and advanced levels relate the orthodox monetary theory with the quantitative theory of money. The heterodox monetary theory, an alternative to the neo-classical monetary approach, has a wholly different perspective on the nature of money. It posits that money supply is essentially endogenous in nature and is determined within the economic system by the requirement for credit across the economy.

0 Comments