Causes and Effects of the 2008 Recession

Published in 2021

Introduction

The inter-bank lending rate, at the height of the economic crisis of 2008-2010, spiked to double digits to reach its highest level since the great depression of the 1930s.1 Such high inter-bank interest rates were outcomes of the severe credit crunch that occurred out of the loss of trust of banks in the ability of other banks to repay monies borrowed in the inter-bank lending market; a development that was instrumental in greatly accelerating the economic downturn. This essay attempts to understand this occurrence in the light of the newly growing discipline of information economics.

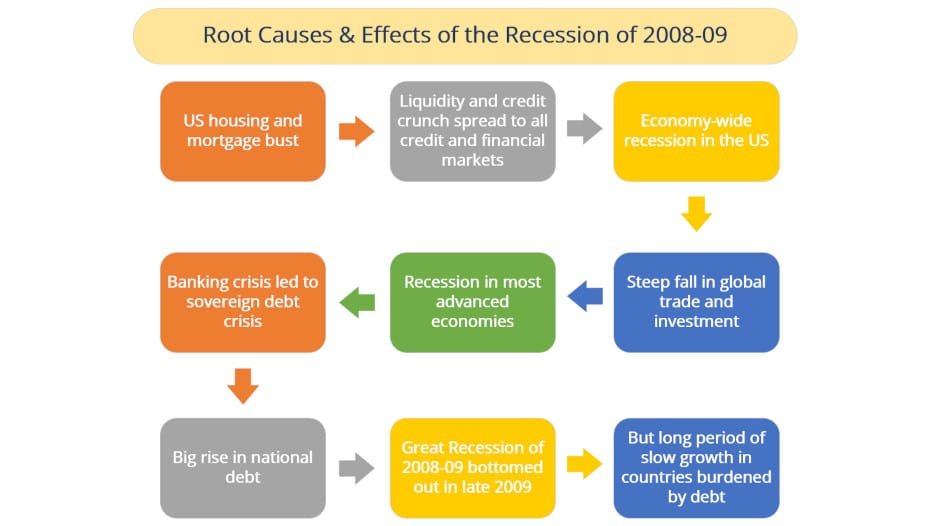

The genesis of the current economic downturn can be traced back to the decision of the US Federal Reserve in 2001 to reduce interest rates dramatically in order to spur a sluggish US economy. Whilst the reduction in interest rates was thereafter slowly adjusted by periodic upward revisions, the sustenance of such low interest levels led to significantly greater bank activity and the development of a housing boom, first in the US and then in other western countries.

Most banks and financial institutions used the opportunity to make huge dubious profits, constructing and selling inappropriate housing mortgages to customers with low incomes and poor credit ratings. With mortgage lending companies pushing sales of housing loans aggressively to such subprime markets, (representing market segments with lower income and repayment capacities), mortgage sellers went all out to sell mortgages, often convincing clients to take mortgages that were beyond their means and where chances of default were high.

Many mortgage companies running out of deposit monies to fund their loans, resorted to risky practices to sustain lending by bundling their poor quality debt and selling consolidated debt packages to other finance companies. Such mortgage debts were purchased by intermediary finance companies in order to spread risks. At this stage, when mortgage bundles were being transferred from mortgage companies to other lenders, credit rating agencies got into the act and gave such mortgage bundles, which essentially consisted of loans to subprime borrowers, good credit ratings. 9Special Purpose Entities (SPE) were created to hold these subprime loan bundles and enable further loans to be organised for fuelling the housing boom.

Figure 1: Causes of Financial Crisis

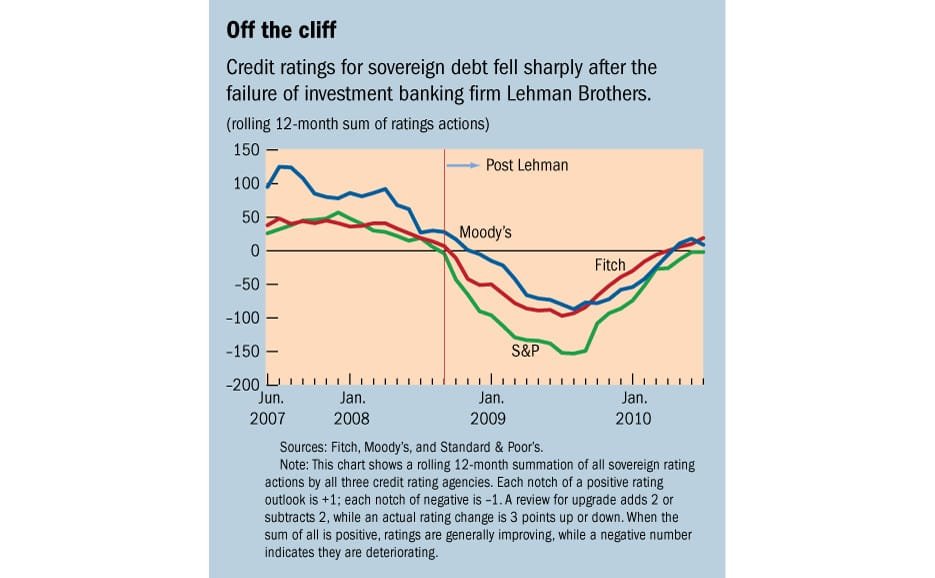

The information available in the banking and financial services space became progressively unclear because of the combination of off-balance sheet financing through SPEs and the interconnectedness of banks, financial institutions and mortgage companies in a structure that was not just highly leveraged, but where a significant proportion of the loans were risky in nature. Whilst many of the institutions involved in these activities were known for their financial and business acumen, the positive ratings provided by reputable credit rating agencies like Standard and Poor created an impression that the money loaned was essentially secure and that housing loans were moreover protected by high property costs.

The enormous financial bubble was thus brought about by the greed of bankers and senior officials of financial institutions, who, helped by credit agencies created a complex web of incorrect and misleading information that was in turn swallowed by a gullible global society greedy for exuberant and often irrational profits and growth.

The end of the housing boom occurred in 2007 when inflation forced the US government to increase interest rates. Whilst such increases in interest rates would have in the normal course not caused more than a temporary blip in the finances of mortgage borrowers, the situation this time around was very different. Mortgages had in the first instance been sold to people with low incomes and low repayment capacities. Mortgage companies had moreover devised schemes where introductory payments were low in order to tempt prospective house owners into buying more expensive properties than they could afford. Such mortgages had repayment instalments, which, whilst being low in the initial years, ballooned significantly thereafter. Such ballooning in mortgage instalments along with higher interest liabilities, led to defaults across the subprime borrower sector in 2007, leading in turn to mortgage foreclosures, the putting up of thousands of such properties on the market and a crash in the US property prices.

The artificial boom occurred in the first place because of the actions of the banking and financial sector to treat essentially finite resources and create wealth by using them as if their availability was infinite. Joseph Stiglitz states that much of the current problems stemmed from a combination of poor regulatory system and an inadequate information environment.

“Stiglitz commented more on the effects of bad information which led to the growth of the economic bubble and what Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan termed the “irrational exuberance” of the 1990s. He noted that the Federal Reserve was attempting to use one instrument (raising interest rates) to achieve two objectives: contain inflation and slowly deflate the economic bubble.”

The failure of accepted information sources like credit rating agencies played a major role in demolishing the credibility of normal information channels, and led many banks to adopt ultra conservative positions and refuse to lend money in the inter-bank lending market.

12 Months Summation of Sovereign Rating

Much of the study of microeconomics is based on the occurrence of phenomena under ideal conditions, namely the perfect information, complete markets and the absence of transaction costs. Micro-economic literature began emphasising the importance of information, leading to the lessening of the ArrowDebreu-Hahn premises and a more rational explanation of the broad scope of connections among social and economic agents in the actual world. The use of information economics, springing from such changes in thinking becomes particularly useful in explaining the various relationships that existed during the subprime crisis and their role in generation of distrust among bankers.

Increasing defaults led to the bankruptcy of many mortgage lenders. The banks and financial institutions that had purchased the mortgage debt from such mortgage companies were also affected badly and had to write-off large scale losses. Such losses were not restricted to the banks in the United States but occurred across banks and financial institutions in the UK and other countries in Europe. A number of banks faced severe credit problems and needed to borrow money from other banks. During this period it became very difficult for banks to gauge the financial health of other companies in the sector. Bank and institutional failures kept occurring sporadically, sometimes occurring after intervals of a few months; each such gap belying people into believing that the worst was over. There was enormous confusion in the financial market over the actual liabilities of different banks and on their credit worthiness and ability to repay borrowed monies.

The liquidity crunch that occurred at this time did not occur just because banks refused to lend to commercial business in the non-banking sector. Much of it was due to the refusal of banks to lend to other banks that needed money to carry out routine banking transactions. When banks lend to commercial organisations in the non-banking sector, their decisions are based on the information that is made available to them by the borrowing organisations and the information on the borrower that is otherwise available. Lending in such cases runs into road blocks either when the information available is unsatisfactory or when it is unavailable. When banks lend to other banks in the inter-bank lending market, such considerations are largely irrelevant and lending takes place on the assumption that repayment within known members of the banking fraternity is a routine matter.

The behaviour of most banks during the onset of the credit crunch was sharply different. Many banks refused to accept the liquidity position or the repayment ability of other banks. Inter-bank lending rates for loans, which were to be repaid within hours, rocketed to double figures, a phenomenon that had not occurred after the depression of the 1930s. The London Inter-Bank Offered Rate, (LIBOR), the rate used by banks globally for short term loans to each other shot up to its highest level ever during the credit crunch. Such high lending rates reflected the lack of confidence of banks that other banks would be able to pay back the borrowed money even if it was borrowed only for a day and came about because of information inadequacy.

The UK government spent more than 110 billion GBP supporting banks during the crisis and provided guarantees and loans in excess of 600 billion pounds. Javier Suarez informed that extension of guarantees on a wide range of bank liabilities could work positively in renewing the confidence of banks in each other; lost because of information asymmetry. The availability of information in the market about the presence of guarantees was expected to bolster confidence throughout the system and neutralise the negative impact of information asymmetry that might make banks hesitant about lending in the inter-bank market.

Suarez however cautioned that guarantees from the government would not substitute banking supervision, (which had been extremely inadequate in the years preceding the crisis) but would complement such measures. 10Such guarantees would enable banks to free themselves from pressures of short term liquidity and concentrate on improving long term prospects or in engaging in required restructuring.

Cost of Capital

Financial managers profess great interest and keenness on the capital structure of their organisations and on associated issues like dividend policies, repurchases of issued shares and other similar topics. Extensive research work is addressing issues related to structuring of capital, the composition of debt and equity in capital structure, and the utilisation of retained earnings.

Capital structuring and budgeting involves the structuring of the capital of the firm in terms of debt and equity; it is considered to be important for decisions that need to be taken by organisations that are starting operations, as well as long running businesses. To elaborate, the capital of a business firm primarily comprises of two components, equity and debt. Equity is provided by the owners of the business and is raised through issue and placement of shares, either through public stock markets or through private channels. Debt on the other hand represents money that is borrowed by organisations from banks, financial institutions and other lenders. Determination of the structuring of these two components is necessary because of their different characteristics and the sharply divergent behaviours of shareholders and lenders.

Miller and Modigliani pioneered research on capital structure and published their capital structuring model in the early 1960s; subsequent years have seen not only the emergence of strong critiques of the MM model but also the surfacing of a number of different capital structuring theories and techniques. These include the pecking order hypothesis, the trade-off hypothesis and the influence of other factors like availability of free cash flows, personal taxes, transaction costs and asymmetric information on capital structuring decisions.

Very obviously the capital available with the firm and its structuring plays a key role in the activity, expenses and profitability of business organisations. The availability of capital enables businesses, not just in small and medium sector but also those that are large, to plan and grow their operations.

The complexities of capital structuring and the efforts of researchers and experts to constantly optimise the function have led to substantial academic and research work on the issue, the emergence of numerous models and the availability of various options to finance managers and corporate managements to optimise and fine tune the capital structure of their firms. Decisions to pay dividends and repurchase shares are also important and affect shareholders; with especial regard to wealth maximisation.

Recent surveys of managers revealed two sets of attitudes, (a) that managers, whilst interested in broad theories about capital structuring, like the pecking order and trade-off theories, show little interest in issues like asset substitution, asymmetric information, transaction costs, free cash flows, or personal taxes, and (b) that managers take little account of factors like agency, signalling, pay-out policy hypotheses, and tax considerations of shareholders in dividend and share repurchase decisions.

Such attitudes, whilst surprising in the context of managers being associated with rational decision making and organisational benefit, are actually quite common and stem from agency relationships.

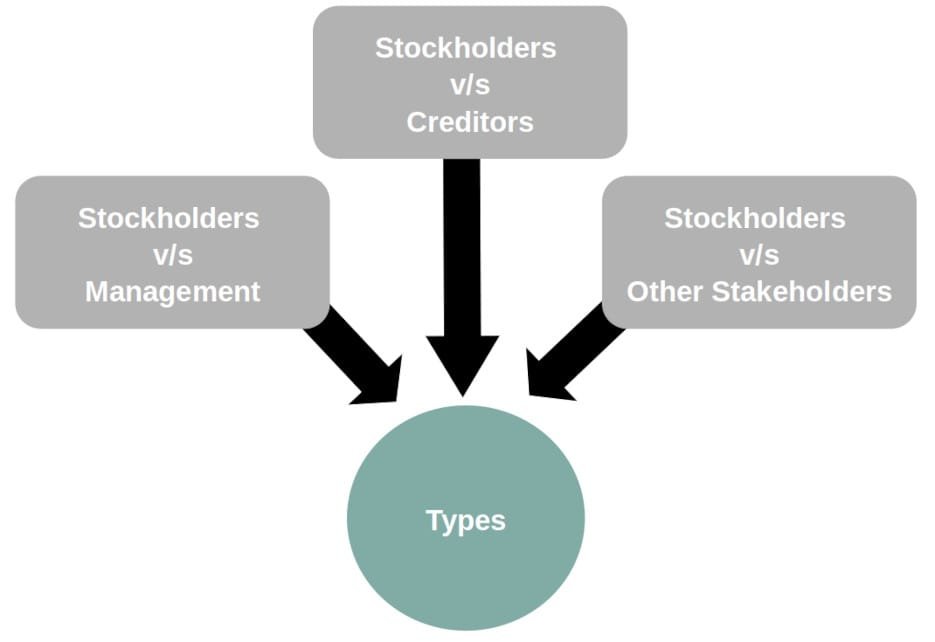

Figure 3: Agency Issues

They are increasingly evident in contemporary business corporations and arise from various aspects of modern-day corporations, namely the ever-increasing distinctions between ownership and management control, increasing business diversification, greater business and industrial segmentation, and enhanced emphasis by investors on immediate performance and return. Agency costs and issues emerge in different forms in such situations; these often include expedient behaviour by managers that are outcomes of self-interest, personal growth objectives, high perquisite consumption, mismanagement, and fraud. Non-optimal or sub-optimal decision-making in areas of investments, corporate structures, investments, and dividend pay-outs are often related to such agency issues.

There is some support for the principle of bounded rationality, (namely that managers can act rationally only up to a limit) in explaining agency costs.

“’A fact is that our attention as scarce resource can only deal with limited information related to complex problems. Given this fact, a critical question is how people make choice in light of limited information and limited computational capacity, and that was what Simon emphasized the issue of “human bounded rationality” in the choice process.”

Managers, even whilst working within the constraints of bounded rationality can however try to make optimal and rational choices by attempting to search for various alternative routes for solving problems or taking decisions, and desist from choosing easier actions before all possible alternate routes have been found, because of restrictions related to time and cognitive processes. Whilst resorting to team work, wherein decisions can be made with the involvement of various people could offer a solution, the problem of lack of cognitive ability and time remains the same. Contemporary managers are also empowered with various technologies to improve their search for alternatives and come to rational and optimal decisions.

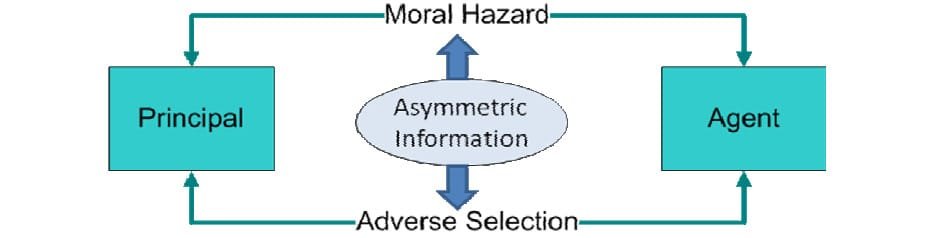

Most experts believe agency issues to be closely associated with asymmetric information. Asymmetric information, in other words, information about the same issue that is available to different extents to different sets of people, is a key reason behind the emergence of agency issues and costs.

Figure 4: Moral Hazard

With members of the management being in possession of much more information about the internal working of corporations than shareholders, the asymmetry in information availability often leads managers to take decisions that would otherwise not be considered. The negative implications of such actions become manifest through reduction of shareholder wealth and broader effect on other stakeholders, like lenders, employees, and members of the society at large. Agency costs are positively related to the presence of external managers and the number of shareholders, whilst they are negatively related to the involvement of owners in business decisions and monitoring by banks.

The survey revealed that whilst CFOs and financial executives were ready to consider widely followed theories in capital structuring they appeared to be far less interested in analysing various alternatives and adopting rational choices. Issues relating to agency theory and asymmetric information were clearly extremely relevant for modern day corporations. Many of the recent scams owe their origin to managers making use of asymmetric information in order to deliberately flout widely accepted covenants of capital structuring, dividend pay-outs and financial management in order to enrich themselves and further their own interests. The economic crisis of 2008 in fact occurred out of the decision by senior bankers and mortgage company managers to disregard capital structuring norms, build up highly leveraged capital structures and expose their organisations to high risks in their search of greater profits and associated bonuses for their own selves.

A greater realisation of the results that flow from asymmetric information and agency factors are leading to increased emphasis on the significance of competitive market environments for managerial labour and the implementation of corporate control via mechanisms for monitoring that aim to restrict the extent of agency divergence through the appointment of institutional shareholders to substitute managerial agency, and the formulation and enforcement of corporate governance codes and practice to reduce oversights by managers and construct required incentive structures.

“The P-A problem could be reduced by giving the outside directors more power/control, because they may be more likely to consider shareholders’ interests. Specific reforms might include increasing the number of outside directors, giving outside directors more control over choosing new directors, allowing outside directors to set compensation for top managers, term limits and mandatory retirement for directors (to increase board turnover).”

Apart from such routes, agency costs and asymmetric information can be controlled by greater formal empowerment of shareholders to question managers, and finally through shareholder decisions to sell and encourage takeovers.

Part 3

Education is possibly the most sought after achievement in advanced as well as developing societies across the world. Long associated with power and the ability to earn wealth, education in today’s global knowledge dominated economy is widely considered to be essential for achieving growth and improvement in personal and working life.

Education as a working and economic sector has by itself expanded greatly in the post Second War Era. Whilst high quality college education in the years directly succeeding the war was associated mainly with a few universities and colleges in the United States, the UK and some countries in Western Europe, it has in succeeding decades expanded exponentially across countries and continents. Thousands of colleges have sprung up not only in the advanced nations but also in Asia, especially in India, China and the countries of South East Asia, East Asia and the Pacific Rim. Whilst countries like the United States and the UK have become entrenched as global leaders in education services, countries like Australia and Canada and cities like Singapore and Hong Kong are trying to position themselves as providers of good quality education. Japan, a global economic leader that has grown from the ruins of the Second World War to become the second richest country in the world is well known for the rigorous quality of its education system and for its excellent colleges and universities.

In the UK the education system has grown significantly in the last four decades, a period that has seen the establishment of numerous new colleges and universities and much wider participation in education. Policy makers in the UK are implementing a number of measures to increase and broad base education through the provisioning of support to people from lower income groups, requiring colleges and universities to provide a range of new courses, making the managements of educational institutions more accountable, and increasing the quality of education. The UK government has frequently espoused the need for better and more widespread education in improving the competitive edge of the country and maintaining its economic and intellectual leadership in a fast globalising world.

Most people in economically advanced nations are able to find numerous avenues of employment after they complete high school, which in turn provide them with adequate income to achieve and maintain reasonable standards of living and quality of life. Despite such conditions there is a growing trend in advanced societies for the young to continue their education after school and obtain university degrees. Such youngsters as also their parents feel that university education can help them in increasing their knowledge, improving their skills, enhancing their awareness and adding to their earning ability. Focussed and good education, people believe can add to their competitive edge during selection processes, interviews, and later in the fulfilment of their job responsibilities.

A number of students as well as parents closely examine the costs of obtaining education with associated financial benefits, whilst assessing the benefits that can accrue from University education. This is truer of working class societies, where the involved children represent the first generation of college goers in families. A university education for such segments of society commonly entails considerable expenses by way of meeting the university fees and the living expenses for the period of the course, as well as the financial burden of loss of earnings during the period of education.

Considering the constantly increasing price of education and the much freer availability of education in the modern day world, many people also believe that the monetary benefits of education, especially in advanced economies, is much lesser than what it is made out to be. Contemporary research reveals that college graduates earn significantly more than those who start work after high school. Specialised education such as that required for law, medicine or accountancy, whilst being more expensive and time consumed, provides greater incomes later on in life. With the higher income earned by better educated people however arising in later years, the additional earning of people who join work after school leads to small differences in earnings in the first 10 years of working life between the two sets of people, those who join work after college and those who opt for college education.

The costs of university education primarily consist of tuition fees and living expenses. Apart from such expenses, which are readily ascertainable, the costs of education include the earning opportunities that can be availed of by people during the years that are required to acquire university degrees. Such costs are difficult to quantify and can vary widely from person to person. The income earned by people in the three or more years required for college education can be used for savings, house deposits, assisting parents, funding education at a later date and other areas that could be important for individuals. The value of university education can be computed by using the statistical information available for average incomes of people with and without university degrees over different time frames, which start from the age at which people complete high school and are ready to go into college, say from ages of 20 to 30, 20 to 35 or 20 to 40.

The income earned by the two groups of people, suitably discounted using a logical discounting rate like the rate of inflation or the average bank lending rate, can be compared to find out the additional income likely to accrue to people with university education. Such differences in income earning potential would however have to be adjusted by deduction of the complete costs of earning university education, both in terms of tuition costs and living expenses.

Whilst such calculations are apt to be significantly affected by the costs and quality of education, which are instrumental in determining the level of post-education earnings of college graduates, the differences between the incomes of the two sets of people are by and large low in the initial years, up to the age of 30 or 35 but increase with time.

The computation of the benefits from a college education can be obtained by the application of simple financial management tools like Payback Period and Net Present Value. The table provided below details a simple method to calculate the financial benefits of higher education over a ten year frame, i.e. from age 20 to age 30, using LIBOR for the discounting rate.

The total value of F over E represents the value of a university education during the first ten years after completion of school.

Researchers however find that university degree holders get many other rewards; the quality of employment they get is better and their unemployment rates are much lesser than those with high school qualifications. College graduates are healthier than those who do not go to college. They contribute more by way of taxes and raise children who are academically better than the children of those who do not go in for higher education.

Increases in the numbers of students wishing to complete their masters can be safely associated with increase in educational loan applications. With educational loans being largely associated with being safe and having good rates of repayment, the increase in demand for such loans should logically result in greater competition between banks for a share of the education loan market, reduction in administrative expenses for disbursing such loans and softening of interest levels. Greater demand for Masters Degrees should thus be negatively correlated with charged interest rates on educational loans. Considering that interest rates should gradually reduce with increasing number of loan seekers, the coefficient of correlation between number of college graduates and rates of interest should be negative.

Randomness in return on human capital is an accepted phenomenon and whilst the acquiring of a MBA degree facilitates the entry of people in corporate life, ultimate corporate success, as represented by achievement of positions on the board or that of CEO or CFO are dependent upon a number of issues like employer attitudes and circumstances, networking ability, HR skills, major illnesses, general health, and numerous career decisions. Benefits and costs in future, such as in this case are often of little present value, even if conventional discount rates are used to measure them.

“We demonstrate that when the future path of this conventional rate is uncertain and persistent (i.e., highly correlated over time), the distant future should be discounted at lower rates than suggested by the current rate.”

The uncertainty that arises out of such circumstances can be loaded as a risk factor in the computation of the discounting rate for computing the present value of an MBA education. Whilst such loading of the discounting rate will lead to a reduction in the income gap, the range of involved uncertainties makes the computation of an appropriate risk factor either arbitrary or extremely complex, requiring the utilisation of advanced statistical models and a plethora of real life data.

References

A. Jennifer, & W.M. Deborah, A Political Theory of Corporate Taxation. Yale Law Journa, (1995)105, no. 2: 325-391.

R. Barrell, &P.E. Davis, The Evolution of the Financial Crisis of 2007-8. National Institute Economic Review (2008), no. 206

J.L Beaulieu, & M. David, Investing in People: The Human Capital Needs of Rural America. Boulder, (1995) CO: Westview Press.

M. Beccerra, & G.K Anil, Trust within the Organization: Integrating the Trust Literature with Agency Theory and Transaction Costs Economics. (1999), no. 2: 177.

C. Brown, & D. Kevin, the Sub-prime Crisis Down under. Journal of Applied Finance (2008), 18, no. 1: 16

M.K. Brunnermeier, Asset Pricing under Asymmetric Information: Bubbles, Crashes, Technical Analysis, and Herding. Oxford: Oxford University Press, (2001)

H. C. Young, On the Information Economics Approach to the Generalized Game Show Problem The American Statistician (1999), 53, no.1: 43.

T. O. Davenport, Human Capital: What It Is and Why People Invest It. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. (1999)

M.A. Dickerson, Over-Indebtedness, the Subprime Mortgage Crisis and the Effect on U.S. Cities Fordham Urban Law Journal, (2009) 36, no. 3: 395

J. Gimeno, B.F. Timothy, C.C. Arnold & Y.W. Carolyn, 1997. Survival of the Fittest, Entrepreneurial Human Capital and the Persistence of Underperforming Firms, (1997) 42, no. 4: 750

J. R. Golden, Economics and National Strategy in the Information Age: Global Networks, Technology Policy, and Cooperative Competition. (1994)Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers

R.H. Haveman, B. Andrew & S.A. Jonathan 2003, Human Capital in the United States from 1975 to 2000: Patterns of Growth and Utilization. Kalamazoo, (2003) MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

T. Healy, Counting Human Capital. OECD Observer a, (1998) no. 212: 31-33

S.M. Horner, & S. Frank, The Valuation of Earning Capacity Definition, Measurement and Evidence. (1999) Journal of Forensic Economics 12, no. 1: 13

J. A. Houlihan, & S.M. Emily, The Subprime Lending Crisis: the Legal Fallout, (2007)

P. Jiraporn, & N. Yixi, Dividend Policy, Shareholder Rights and Corporate Governance.(2006), Journal of Applied Finance 16, no. 2: 24

Z. Karake-Shalhoub, Trust and Loyalty in Electronic Commerce: An Agency Theory Perspective (2002), Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

C.B. Leinberger, The Next Slum, the Subprime Crisis Is Just the Tip of the Iceberg. Fundamental Changes in American Life May Turn Today’s McMansions into Tomorrow’s Tenements, (2008), The Atlantic Monthly, March, 70

I. Macho-Stadler, & J. David Pérez-Castrillo, An Introduction to the Economics of Information: Incentives and Contracts,(1997) Oxford: Oxford University Press

B.H. Malmgren, The Credit Crisis Is Not Over: The Anatomy of a Financial Unravelling, (2007) The International Economy, Fall, 58

R. Miller, & W. Gregory, Investing in Human Capital, (1995), OECD Observer a, no193: 16-19.

F. Milne, Finance Theory and Asset Pricing, (1995)

N.R. Netusil & H. Michael, The Economics of Information: A Classroom Experiment, Journal of Economic Education (1995), 26, no. 4: 357-363

R. Newell, G. Richard & W. Pizer, Discounting the Distant Future: How Much Do Uncertain Rates Increase Valuations, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, (2001)

H. Osano, & T. Tachibanaki., eds. Banking, Capital Markets, and Corporate Governance, (2001),

F. C. Pierson, The Education of American Businessmen: A Study of University-College Programs in Business Administration, (1959), New York: McGraw-Hill.

B. A. Riahi-Belkaoui, Capital Structure: Determination, Evaluation, and Accounting, (1999), Westport CT: Quorum Books.

M. Sargent, The Blame Game: Moralizing Won’t Fix the Economy, (2008), Commonweal, November 7, 8

L.C. Silva, Luis, G., Marc, R. Luc, Dividend Policy and Corporate Governance Oxford, (2004) Oxford University Press

G.P. Stapledon, G. P. Institutional Shareholders and Corporate Governance, (1996) Oxford: Clarendon Press.

J. Stiglitz, The roaring nineties by Joseph Stiglitz, (2003).

J.Suarez, Bringing money markets back to life, (2008).

P. Swagel, The Financial Crisis: An Inside View. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, (2009), 1

Swanson, Zane, Bin Srinidhi, & S. Ananth, The Capital Structure Paradigm: Evolution of Debt/Equity Choices, (2003), Westport, CT: Praeger

C, Torr, Equilibrium, Expectations, and Information: A Study of the General Theory and Modern Classical Economics, (1988) Boulder, CO: Westview Press

B. Weinbaum, The Practice of Performance in Teaching Multicultural Literature. Multicultural Education, (1999), Fall, 16

J.R. Graham, & R.H. Campbell, The Theory and Practice of Corporate Finance, Evidence from the Field, Journal of Financial Economics, (2001), 60, no, 187- 243

B. A. Graham. J. R, Harvey, C. R, & R. Michaely, Payout Policy in the 21st Century, Journal of Financial Economics, (2005), 77, no, 483 – 527

M, Jensen, & W. Meckling, Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behaviour,

Agency Costs and Ownership Structure’, Journal of Financial Economics, (1976), Vol. 3, 4, no, 305 – 60

M.C.Jensen, Agency Costs of Free Cash flow, Corporate Finance and

Takeovers, American Economic Review, (1986), Vol. 76, no, 323- 329

S.C.Myers, Capital Structure, Journal of Economic Perspectives, (2001), Vol.15, No. 2, no, 81 102

More From This Category

Does Capital Structure Matter

The capital structure of a modern corporation is, at its rudimentary level, determined by the organisational need for long-term funds and its satisfaction through two specific long-term capital sources, i.e. shareholder-provided equity and long-term debt from diverse external agencies (Damodaran, 2004). These sources, with specific regard to joint stock companies, retain their identity but assume different shapes.

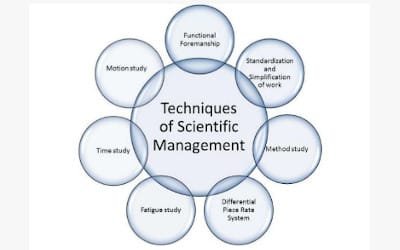

Principles and Applications of Taylorism

The work of Fredrick Taylor, (1856 – 1915), widely known as the founder of scientific management, has been instrumental in shaping management thought and action in diverse areas of business and industry for the major part of the 20th century.

Strategic Analysis: The Case of Sainsbury’s Plc

The application of strategic analytical models to an organisation and the evaluation of their results helps in the generation of a comprehensive corporate strategy.

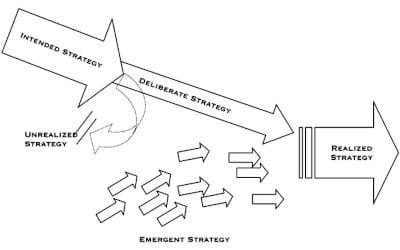

Deliberate and Emergent Schools for Strategy

Deliberate and Emergent strategies are situated at two ends of the strategic continuum, but have been used with success by modern organisations.

Strategy Formulation and Management of Change Application to a Healthcare Organisation

The application of strategy to a particular business sector makes it easier to understand its practical implications than a generalised discussion.

Accounting is a Strategic Business Tool

Several experts, from the 1980s onward, have focused on the importance of strategic management accounting and presented strong cases for its adoption.

0 Comments