What is the difference between Orthodox and Heterodox Economics?

Published in 2021

Introduction

There are two different outlooks on the role of money in the economy, namely the frameworks of the Orthodox school and the Heterodox schools of thought; their understanding is necessary to develop a great comprehension of money and to decide upon the ways in which it eases the functioning of the economy. Whilst the perception of money often appears to be unambiguous, it can, according to these two schools of thought serve completely different purposes!

Orthodox economists recognise money as a way for conducting transactions, suggesting that money’s solitary purpose is the enabling of exchange of goods and services. The heterodox school of thought conversely sees money to be the final product that is generated from engaging in an exchange of goods and services. To go a step further, money works as the medium of exchange in the orthodox framework, whilst businesses and individuals offer goods and services in exchange for profit in the heterodox approach.

The Orthodox Approach

The orthodox approach is possibly the most recognised and widely debated theory of money on account of its simplicity! The orthodox theory posits that markets evolved first, much, much before money came into existence. These markets developed on account of the natural disposition of people for exchange. Whilst humans originally tried to be self-sufficient for all their needs, they soon stumbled upon the conveniences of barter. The transactions that took place made use of barter, with people aiming to obtain goods that they did not possess in exchange for the products owned by them. Successful barter required a double coincidence of wants, i.e. two people, each of whom had goods that were desired by the other; this led to the need for a common medium of exchange, which radically lowered transaction costs.

The barter system was effective only when the dealings between individuals were basic and simple. It however failed swiftly with enhancement of social complicity. The most important inadequacy with the barter system and perhaps the most important cause for societies to graduate to the monetary system related to the challenges associated with the double coincidence of wants and its logistics. Adam Smith stated that “the butcher seldom carries his beef to the baker or the brewer in order to exchange it for bread or beer”. This example illustrated the consequent logistical dilemma. The double coincidence of wants, firstly leads to the dilemma that the baker and the brewer may not possibly have any need for beef, which makes it difficult for the butcher to obtain bread and beer in order to arrange for a complete dinner; this implies that the butcher was essentially dependent on the desire of other tradesmen for beef! It was secondly difficult for the butcher to carry his commodity with him in order to satisfy the double coincidence of wants. Individuals thus took their commodities to markets where they exchanged their goods for money and used that money to purchase the goods and services required by them. The members of society thus converted their grains, livestock and tobacco into gold coins through market transactions and then proceeded to purchase the commodities required by them with these coins. The coins increasingly became desirable for market participants because they could be used to purchase goods and services on account of their universal acceptance! It is obviously easy to understand that coins were far more efficient to handle than flocks of horse, cows or sheep.

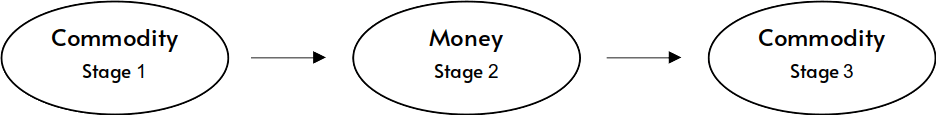

The diagram detailed below illustrates this movement from commodity to money and again to commodity.

Figure 1: MOVEMENT FROM COMMODITY TO MONEY AND AGAIN TO COMMODITY (Source: Slawson, 2014, p 1)

The diagram illustrates that a person enters the market place with a specific commodity. He thereafter sells this commonality for money, which can be in diverse forms like jewels, animal skins or gold. The consumer can thereafter purchase the commodity he wants with the money in stage three. This illustrates how the introduction of money affected the evolution of barter of goods and services and the maturing of barter transactions to those involving buying and selling.

The orthodox framework declares that money is essentially exogenous or created through the barter system in order to resolve the dilemma associated with double coincidence of wants. The progression, in such circumstances commences with the exchange of commodities amongst various individuals in the marketplace until the bartering transactions become too difficult in terms of satisfying needs or on account of difficulties with regard to quantity and divisibility. It is easy to see the difficulty in dividing livestock for a litre of kerosene of fuel! With mismatches like this between different types of goods and services, barter became practically impossible and resulted in the adoption of a single commodity as a convertor, which was furthermore divisible into small quantities in order to make transactions convenient and fair.

The concept of fairness and equitability led to the emergence of the idea of just price. It was obvious that the owners of different commodities had to price their products at universally acceptable levels; the failure to do so would result in the development of various imbalances and doom it to failure. The concept of just or a fair price enabled market participants to change their diverse goods and services into commodities, which were mostly silver, gold or other divisible metallic items, which could be denominated in appropriate currency.

Money is considered to be neutral in the orthodox approach because it does not serve any purpose other than the facilitation of exchange. The orthodox theory declares that economic agents spontaneously decided upon gold in the first instance. Governments subsequently made use of paper money to frame convertibility into gold. Governments were however always motivated to spend more than was allowed by their good reserves and were thus consequently forced to abandon convertibility. Fiat money thus came to dominate markets.

Money, in this analysis, is thus a commodity that follows the dictum of supply and demand. Its main purpose is to be a medium of exchange that greases the procedure of exchange of goods. The meta-theory supporting this view is the neoclassical supposition that individuals are able, through constant and rational efforts for maximising of utility, able to change the numerous bilateral exchange ratios between various commodities into a solitary price for any uniform profit. Money thus is a technical device for facilitating this process. Whilst the primary function of money seems to be clear and logical in the orthodox theory, i.e. a medium of exchange that lubricates markets and reduces transaction costs, the origin of money continues to be ambiguous. It can possibly be explained as a “helicopter drop” theory of money. Mishkin (2007) stated that the helicopter drop idea stood at the core of the orthodox analysis of changes in money supply and their impact.

The government, as per the orthodox theory is quite clearly the source of money (Laidler, 1997). Graeber (2001) stated that governments control the reserve requirement ratio and can thus manage the supply of money. With the central bank or the national government determining the reserve requirement ratio, it can control reserves and control money supply well through the acceleration or deceleration of the monetary base (Graeber, 2001). Reserves are dominated in fiat money, a fact that results in the problem of the system (Wray, 2012b). Fiat money in orthodox theory stands for money that has nominal, rather than real value because it is not backed by gold (Bernstein, 2008). The government, because it can issue substantial volumes of money, lures the private banking sector to follow suit, which makes the system potentially inflationary (Wray, 2012b). Monetarists state that reverting back to a gold standard or enforcing monetary rules that will prevent governments from spending too much or with too much speed is the only remedy to this sort of problem (Laidler, 1997).

Heterodox Approach

This orthodox justification of the genesis of money has been opposed by the heterodox school (Greco, 2001). The heterodox school states that the essence of money lies in its capacity for computing abstract value and not in its medium-of-exchange role; this enables it to become the money of account (Greco, 2001). It argues that the orthodox theory on money has been unable to explain the generation of unit-of-account function of money or demonstrate the natural emergence of a steady measure for gauging value (Greco, 2001). Ingham (2004) stated that it was difficult to visualise how a money of account could appear from numerous bilateral barter exchange ratios that are based upon subjective preferences.

The story of money in the heterodox approach commences with the state or specific centralised institutions, rather than with the wide acceptance of some commodity as a medium of exchange in order to facilitate commercial activity (Smithin, 2003). Money in such circumstances is utilised as a money of account that has been conceived and established by a authoritarian governmental figure and implemented in terms of a unit of measure, like for example inches, litres or pounds (Smithin, 2003). This concept bears fruit on account of the obligation of individual to pay debts, as defined by the state government (Hyman, 1992). The demand for money is created through the placement of an obligation on a national population in the form of interest, taxes or penalties (Hyman, 1992). The government, in such circumstances creates a demand for a commodity considered to be satisfactory for payments through the development of debt obligations (Naqvi & Southgate, 2013).

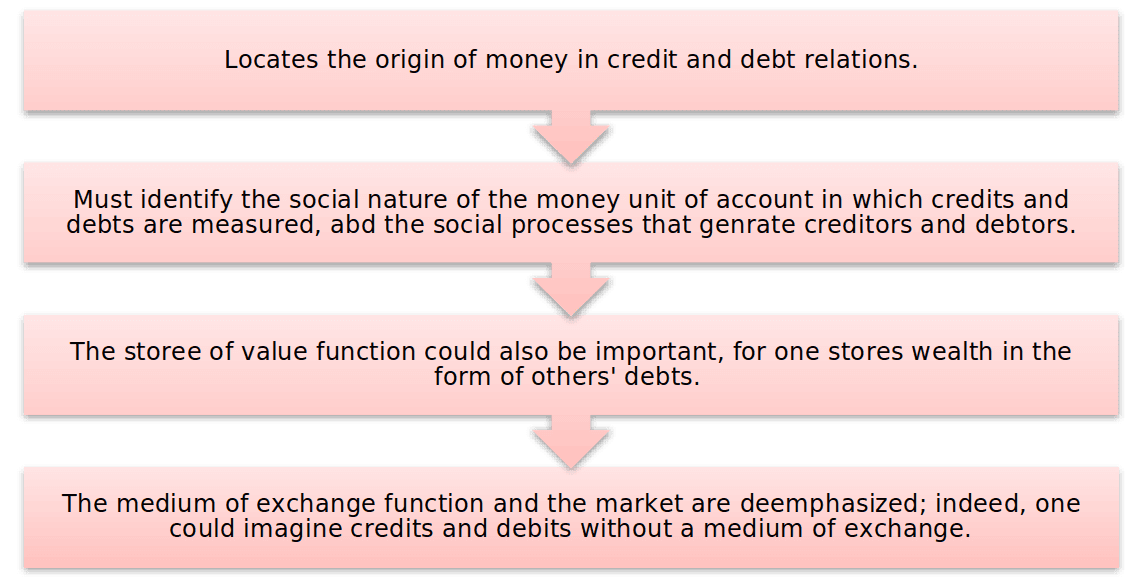

FIGURE 2: THE HETERODOX ALTERNATIVE (Source: Wray, 2012a)

Discussion and Analysis

Traditionally literature on economics, both at the introductory and advanced levels relate the orthodox monetary theory with the quantitative theory of money. Money supply, in such literature, is felt to be controlled by the Central Banks of countries and thus constitutes an exogenous parameter that is determined by monetary policy objectives. The Central Banks manage the monetary base of their countries, i.e. the sum of money in circulation and the necessary required reserves of their banking systems in line with their judgment with the help of specific instruments, i.e. open market operations and specifically required reserve ratios.

The process of money creation occurs through the operation of money multipliers. This is thought to be constant, or, at any rate, steady over time, allowing the Central Banks to successfully manage the total money supply. Whilst the tendency to deposit and the demand for credit are influenced by the condition of the market and internal features of economic agents, the Central Banks can substantially shape and determine the amount of issued credits with their policy tools. This outlook considers that the stable money demand function essentially relates monetary aggregates with the measure of entire income in the national economy, thereby allowing monetary policy to be effectual in managing and controlling aggregate demand.

This view implies that the transmission mechanism is based upon money supply as the policy instrument. Alterations or increases in the money supply can result in non-equilibrium conditions on the money market, namely excess supply of money, which, in turn can result in alterations in consumptions and investments and reductions in nominal interest rates. The demand for money consequently adjusts accordingly and equilibrates the condition in the money market; this results in changes in the aggregate demand, which increases accordingly. This suggests that the demand for money should be comparatively inelastic and consumption and investment should be interest-elastic for monetary policy to be efficient. Inflation is thus considered to be the consequence of excessive money supply in conformity with this reasoning; the increase in the aggregate demand that is driven by the enlargement in money supply leads to the development of an upward pressure on prices when production facilities are constrained.

Friedman stated, in his presentation of his monetarist view that alterations in the amount of money in the long run have a trifling impact on real income; money is not of much consequence and non-monetary forces are the ones that matter for changes in real income over long periods; he stated that money is of consequence only for movements in nominal income and for short-run alterations in real income.” (Friedman, 1974, p. 27). Monetarists thus state that increase in exogenous money supply increase can produce an output effect, but only in the short term.

The heterodox monetary theory, an alternative to the neo-classical monetary approach, has a wholly different perspective on the nature of money. It posits that money supply is essentially endogenous in nature and is determined within the economic system by the requirement for credit across the economy. This theory postulates that Central Banks can effectively control the interest rate through the adoption of specific policies. Several central banks across the world in fact work on managing the interest rate rather than trying to influence any of the monetary aggregates. The short-term interest rate policies of central banks determine the costs of liquidity and losses on this account for the commercial banks when they issue credit; this serves as a bench-mark for movement of short-term credit rates in the economy. The various further processes of interaction between the credit policies and behaviours of the commercial banks and the consequent monetary aggregates and income alterations are described in different ways in three relevant approaches within this thread of thought, namely (a) accommodationist, (b) structuralist and (c) liquidity preference.

Accommodationalism is specifically concerned with the attitudes and approaches of both the commercial banks and the central bank towards the economic agents, more specifically the business forms, which are the protagonists of the economy. It constitutes the unadulterated reaction of these institutions chiefly towards their production needs. These requirements are actually proxied or measured through demand for credit borrowing or aggregate demand

Structuralism can trace its genesis to the theories advanced by Minsky. The Central Bank and the auxiliary commercial banks form the most significant player in the economic system and have the right to accommodate reserve needs in this post Keynesian approach, even though economic agents and firms also play important role in it. This thread of thought entails the leaving behind of inert accommodation and the proactive embracing of resistance on credit expansion. This can result in a money supply curve that slopes. Structuralism furthermore does not challenge or contradict the classical perception view regarding the left-to-right direction of the money–income relationship.

The Liquidity Preference approach posits that the challenges and difficulties associated with expansion of bank credit and the meeting of the aggregate loan demand requirements of economic agents and business firms are chiefly shaped by the role and the behaviours of various households and their agents, whose deposits are treated as liabilities in the financial statements of banks and are related with the responses of commercial banks via their asset management policies.

When considering the details of the origination of money and its use under both the Orthodox and Heterodox approaches, it should be remembered that the Orthodox approach is based in the barter system, with lineage to primitive societies who exchanged one good for another. Due to the acknowledgement of problems with the barter system, commodities were more or less converted into a widely accepted divisible form of money to facilitate exchange. However, this system only proves affective in moving commodities from one individual to another, without any other inherent benefits such as the creation of wealth due to the neutrality of money in this framework. This is a completely different model from the Heterodox approach, which looks to create wealth within the economy and is accomplished through a system where money matters. For money to be an important component of the system, the state must initiate a debt obligation that is payable with only the sovereign currency of the state. The debt obligation causes citizens to demand the money because they must acquire it to pay off the debt obligation and to acquire this money in the first place, the state must be willing to employ citizens to help move resources to the state and compensate their labour with the state currency. With the state paying and accepting debt payments in the form of its own sovereign currency, the question of affordability is irrelevant, that is to say the government can afford all things denominated in its own currency. The policy implications for this fact allows the government to increase its spending to afford all unemployed resources during periods of poor economic growth and conversely increase the debt obligation to slow down the economy. Conclusively, the Heterodox approach allows for the economy to be much more efficiently managed so full employment or prosperity can be achieved.

References

Allen, H., & Dent, A., (2010), “Managing the circulation of banknotes”, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Vol. 50, Iss (4): pp. 302–10.

Bell, S., (2001), “The Role of the State and the Hierarchy of Money”, Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 25: pp 149-163.

Bernstein, P., (2008), A Primer on Money and Banking, and Gold, NY: Wiley.

Cecchetti, S., (2008), Money, Banking, and Financial Markets, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Evans, T., (2009), “Money and finance today”, In. Grahl, J. (ed), Global Finance and Social Europe, Chelteham. Edward Elgar.

Farag, M., Harland, D., & Nixon, D., (2013), “Bank capital and liquidity”, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Vol. 53, Iss (3): pp. 201–15.

Friedman, M., (1974), “A theoretical framework for monetary analysis”, in R.J. Gordon (ed.), Milton Friedman’s Monetary Framework: A Debate with his Critics, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Fuster, D. R., (2002), “Economics and the Market Economy”, In D. R. Fuster, The Age of the Economist, (pp. 7-12). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Graeber, D., (2001), Toward an anthropological theory of value: the false coin of our own dreams, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Greco, T.H., (2001), Money: Understanding and Creating Alternatives to Legal Tender, White River Junction, Vt: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Hahnel, R., (2002), The ABCs of Political Economy, London: Pluto Press.

Heilbronner, R., & Thurow, L., (1998), Economics Explained, New York: Touchstone.

Hyman, P. M., (1992), “The Financial Instability Hypothesis”, Working Paper no 74, The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection, Available at: http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp74.pdf (accessed November 16, 2015).

Ingham, G., (2000), “Babylonian madness’: on historical and sociological origins of money”, in: Smithin, J. (ed). What is money?, London: Routledge.

Ingham, G. K., (2004), The Nature of Money, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Innes, A. M., (2004), “What is Money?”, In L. R. Wray, Credit and State Theory of Money, Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Kelton, S., (2012), “Orthodox Money vs. Heterodox Money Lecture”, Advanced Macroeconomics, Kansas City, MO, USA.

Laidler, D., (1997), Money and Macroeconomics: The Selected Essays of David Laidler, NY: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Mallard, G., (2012), The Economics Companion, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Manning, M., Nier, E., & Schanz, J., (2009), The economics of large-value payment and settlement systems: theory and policy issues for central banks, Oxford University Press.

Mishkin, F.S., (2007), The Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets, Boston: Addison Wesley.

Naqvi, M., & Southgate, J., (2013), “Banknotes, local currencies and central bank objectives”, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Vol. 53, Iss (4): pp. 317–25.

Poor, V.H., (2009), Money and Its Laws: Embracing a History of Monetary Theories, and a History of the Currencies of the United States, NY: The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd.

Ryan-Collins, J, Greenham, T., Werner, R., & Jackson, A., (2011), Where does money come

from?: A guide to the UK monetary and banking system, London: New Economics

Foundation.

Slawson, C., (2014), “Essays in Monetary Theory and Policy: On the Nature of Money “, Available at: http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2014/02/essays-monetary-theory-policy-nature-money-10-2.html (accessed November16, 2015).

Smithin, J., (2003), Controversies in Monetary Economics, NY: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Tcherneva, P.R., (2001), Money: A Comparison of the Post Keynesian and Orthodox Approaches, In: Oeconomicus, Volume IV, Winter, pp. 109-114.

Toporowski, J., (2010), Why the world needs a financial crash and other critical essays on finance and financial economics, London: Anthem Press.

Wray, R., (1999), “The development and reform of the modern international monetary system”; in: Deprez, J. and J.T. Harvey (eds), Foundations of International Economics: Post Keynesian Perspectives, London: Routledge.

Wray, L. R., (2001), “The Endogenous Money Approach”, Working Paper No. 17. Available at: http://www.cfeps.org/pubs/wp/wp17.html (accessed November16, 2015).

Wray, R.L., (2012a), “Introduction to an Alternative History of Money”, Working Paper No. 717, Levy Economics Institute of Brad College, Available at: http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_717.pdf (accessed November 16, 2015).

Wray, L. R., (2012b), Modern Money Theory, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

Wray, L. R., (2013), Monetary Theory and Policy Lecture, Kansas City, MO: USA.

More From This Category

Does Capital Structure Matter

The capital structure of a modern corporation is, at its rudimentary level, determined by the organisational need for long-term funds and its satisfaction through two specific long-term capital sources, i.e. shareholder-provided equity and long-term debt from diverse external agencies (Damodaran, 2004). These sources, with specific regard to joint stock companies, retain their identity but assume different shapes.

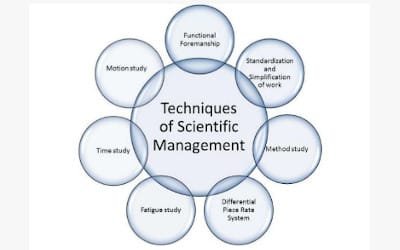

Principles and Applications of Taylorism

The work of Fredrick Taylor, (1856 – 1915), widely known as the founder of scientific management, has been instrumental in shaping management thought and action in diverse areas of business and industry for the major part of the 20th century.

Strategic Analysis: The Case of Sainsbury’s Plc

The application of strategic analytical models to an organisation and the evaluation of their results helps in the generation of a comprehensive corporate strategy.

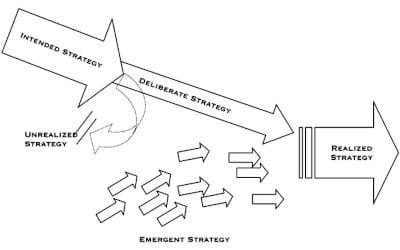

Deliberate and Emergent Schools for Strategy

Deliberate and Emergent strategies are situated at two ends of the strategic continuum, but have been used with success by modern organisations.

Strategy Formulation and Management of Change Application to a Healthcare Organisation

The application of strategy to a particular business sector makes it easier to understand its practical implications than a generalised discussion.

Accounting is a Strategic Business Tool

Several experts, from the 1980s onward, have focused on the importance of strategic management accounting and presented strong cases for its adoption.

0 Comments