Corporate Governance in the light of Agency and Other Theories

Published in 2016

Introduction & Overview

The importance of corporate governance is being felt sharply in the contemporary era, not just because of the numerous scams and the various episodes of poor corporate governance that started surfacing in the 1990s and culminated in the subprime and banking scandals of 2007 and 2008, but also because of greater general awareness about the need for ensuring appropriate corporate governance for the protection of stakeholders (Daily, et al, 2003, p 372). Theories on corporate governance have in the past been dominated by the agency theory and the principal-agent concept, which examine and elaborate the various sources of friction that can arise between principals and agents in various areas of enterprise and life (Daily, et al, 2003, p 372). In the case of joint stock corporations, the principals, i.e. the shareholders, think of wealth maximisation as the primary objective of corporate functioning, even as their agents, namely the managers of these corporations, have and work towards achieving a range of personal and joint objectives that are often contrary to those of their principals (Daily, et al, 2003, p 372).

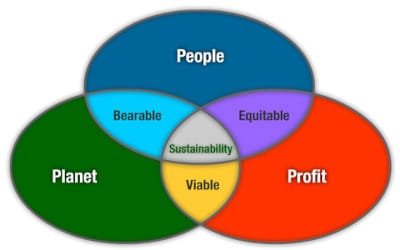

Heightened awareness about corporate governance has in recent years led to the emergence of a number of theories on corporate governance. Corporate governance theory commenced with the agency theory, grew into the stewardship and stakeholder theories, and evolved further into the resource dependency, transaction cost and political theories (Clark, 2004, p 78). Other ethics related theories like the business ethics, virtue ethics, feminist ethics, post modernism ethics and discourse theories have also been developed in recent decades (Clark, 2004, p 78).

The corporation is a dominant and powerful contemporary institution. Reaching across the globe, modern corporations influence economies and societies (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 89). The emergence of globalisation and reduction of governmental control has reduced the accountability of these organisations to national regulatory systems (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 89). With shareholders seen to be losing their trust in the running of these institutions, corporate governance plays an important role in the management of these organisations today (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 89).

Whilst a widely accepted definition of corporate governance is yet to emerge, it can be described as the processes and structures that control and direct organisations. It is made up of rules that govern relationships between shareholders, managements of firms and stakeholders (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 89). The agency theory fundamentally underlines corporate governance (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 89). Apart from the agency theory, a number of other theories are now used to explain, understand, and improve corporate governance processes.

Agency Theory

The agency theory, which has its roots in economic theory, has been elaborated and developed by Alchian and Demsetz, (1972, p 773 to 774), and Jensen and Meckling (1976, p 307), who defined it as “the relationship between the principals, such as shareholders and agents such as company executives and managers”. It states that shareholders, the principals of companies, hire individuals to work for them. They delegate the running of business to such agents, the directors and managers of their companies. The agency theory fundamentally reduces corporations to two participants, namely shareholders and managers (Eisenhardt, 1989, p 57). It further elaborates that whilst agents are expected to work for shareholders and maximise their wealth, such agents actually have a number of interests and objectives of their own that lead them to take operational decisions that are sometimes not in the best interests of the shareholders (Eisenhardt, 1989, p 57). Agency issues were first brought up by Adam Smith in the 1700s and have since been explored and developed in detail (Eisenhardt, 1989, p 57). The agent may be influenced by self-interest and behave in an opportunistic manner that can lead to sharp divergence between the interests of the principal and the pursuits of the agent (Eisenhardt, p 57).

Public corporations are distinguished by separation of ownership and control of assets. Whilst ownership of assets is vested in shareholders, control over such assets rests with professional managers, namely the agents (Jensen & Meckling, 1992, p 64). Managers engage in actions, whose consequences are borne by shareholders (Jensen & Meckling, 1992, p 64).

Two types of managerial failures lead to their being unable to act as perfect agents of shareholders. Such failures can in the first place arise from genuine and unintentional mistakes in discharge of managerial responsibilities (Moldoveanu & Martin, 2001, p 4). They can secondly arise from failure of managerial integrity, the pursuit of self-interest and wilful managerial behaviour, and can negatively influence organisational asset valuations (Jensen & Meckling, 1992, p 64). Shareholders engage in numerous types of reward and punishment mechanisms, along with ratification and monitoring processes that direct, control, monitor and motivate agents to work in directions that are aligned with shareholder interests (Moldoveanu & Martin, 2001, p 4). Such agency issues are further affected by various elements like decision rights, knowledge, and incentives.

A number of veils insulate decision makers from the results of their actions and add to inefficient agency working (Moldoveanu & Martin, 2001, p 4). Legal veils insulate shareholders from corporate liabilities and protect them from the negative effects of decisions that otherwise have difficult financial consequences (Jensen & Meckling, 1992, p 64). Informational veils (a) insulate shareholders from the information required by them to run companies competently, (b) insulate members of BODs from relevant information about companies, and (c) insulate managers from information that their employees may have and keep from them (Jensen & Meckling, 1992, p 64). Motivational veils insulate shareholders from debt and legal culpabilities of their organisations, insulate members of BODs from the consequences of their actions, and insulate top managers and employees from shareholder action, if their remuneration packages are not affected by alterations in value of shareholder equity (Moldoveanu & Martin, 2001, p 4).

Agency theorists suggest a number of governance mechanisms for overcoming agency inefficiency (Moldoveanu & Martin, 2001, p 7). These include the alignment of decision rights with specific knowledge, the alignment of incentives with decision rights, and the designing of suitable monitoring mechanisms for performance measures, which form the basis of award of bonuses and options. Many corporations also try to align shareholder and managerial interests by the progressive increase of ownership stakes for managers through stock options and alignment of remuneration with corporation value (Eisenhardt, 1989, p 63).

Alternative Corporate Governance Theories

Imperfections in principal-agent relationships come from making profit maximisation the most important of corporate objectives (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 92). With shareholders having the option to choose from a range of investment alternatives, it is but natural for them to perceive (a) wealth maximisation to be the most important reason for choice of corporate investments and (b) the main objective of organisational managements (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 92). It is not difficult, in this context, to imagine that agents may also have various personal objectives for improving their careers, market worth and financial conditions, which, in turn, can lead them to engage in actions that are contrary to the objectives of shareholders (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 92). Contemporary times have thus led to the evolution and development of different theories of corporate governance (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 92).

Stewardship Theory

The stewardship theory is grounded in psychology and sociology. It concerns the protection and maximisation of shareholder wealth by stewards through the performance of firms, because doing so maximises the utility functions of stewards (Clark, 2004, p 92).

The stewardship theory, unlike agency theory, calls upon members of the senior management to integrate their goals with those of the organisation, (as stewards), rather than to adopt individualist perspectives (Clark, 2004, p 92). Experts like Fama (1980, p 288) stress that directors and other executives manage their careers so that they can be seen to be effective stewards of their organisations. The stewardship model is particularly relevant in Japan where workers assume the role of stewards, take ownership of their jobs, and engage diligently in their work (Clark, 2004, p 92).

The theory furthermore suggests the unification of the role of the chairman with that of the CEO in order to reduce agency costs and to provide the CEO with a greater role as an organisational steward (Clark, 2004, p 92). Donaldson and Davis (1991, p 65) empirically found that returns could be improved by combining the agency and stewardship theories. It needs to however be noted that the stewardship theory also focuses on little more than maximisation of shareholder wealth by providing corporate managements with the role of stewards (Clark, 2004, p 92).

Stakeholder Theory

The stakeholder theory emerged in the 1970s and was later developed by Freeman (1984, p 76), wherein he attempted to build a governance model that incorporated corporate accountability, not just to shareholders but to a wider range of stakeholders.

The stakeholder theory derives from sociological and organisational disciplines and is less of a unified theory and more of a tradition that incorporates philosophy and ethics with law, economics and organisational science (Rusconi, 2007, p 10). This theory, unlike the agency and stewardship theories, suggests that organisational managers do not exist only to serve the interests of shareholders, but are required to serve a network of relationships that include business partners, suppliers and employees (Rusconi, 2007, p 10). Advocates of this theory state that this network group is as important as the owner-manager-employee relationship, the base of agency theory, and that diverse stakeholder deserve and require management attention (Clarkson, 1995, p 94). Such experts argue that many groups participate in businesses to obtain benefits and that it is not just unfair and unjust, but also impractical to subordinate their benefits and objectives to those of shareholders (Clarkson, 1995, p 94). Organisational wealth should be created, not just for shareholders, but for all stakeholders (Clarkson, 1995, p 94).

Whilst the stakeholder theory focuses on ensuring that ethics is not subjugated to economic success and maximisation of shareholder wealth, its application is dependent upon the localisation of organisational stakeholders, “namely who are the involved stakeholders”, the elaboration of the rights of these stakeholders, and the bringing about a unification between stakeholder benefits and shareholder wealth (Rusconi, 2007, p 10). The application of the stakeholder theory could also lead to issues of (a) hierarchy of stakeholder rights, (b) the satisfaction of demands of non-legitimate stakeholders when they come in conflict with those of legitimate stakeholders, and the path to be followed if such conflicts cannot be reconciled (Rusconi, 2007, p 10). Donaldson and Preston (1995, p 67) however argue that as this theory concerns the interests of all stakeholders and all such interests have intrinsic values, one set of interests cannot be allowed to dominate others.

Resource Dependency Theory

The resource dependency theory focuses on bringing about corporate governance through the actions of the board of directors in the provisioning of access to resources that are needed by firms (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 94). Hillman, et al, (2000, p 236), state that directors play important roles in securing or providing required resources to organisations through their relationships with the external environment. Other theorists state that the appointment of directors from independent organisations is an important method for obtaining access to resources that are critical to organisational success (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 9). External directors who are experts in areas like law, finance, HR or IT can provide information and advice that could otherwise be expensive and difficult to secure (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 94)

The appointment of directors from four categories, namely insiders, support specialists, business experts and community influencers can help in providing access to various types of resources and can ensure ways and means to marry the objectives of shareholders with those of a range of stakeholders (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 94).

Ethics Theories

Whilst agency theory, along with stewardship, stakeholder and resource dependency theories, constitutes the base resource for formation of corporate governance processes, a number of ethical theories like business ethics, virtue ethics, feminist ethics and postmodern ethics are also associated with corporate governance (Crane & Matten, 2007, p 41).

Business ethics relates to the study of activities, decisions and circumstances in business, that concern issues of right and wrong (Crane & Matten, 2007, p 41). With business influence and power in society being stronger than ever in the past, businesses now contribute immensely to society through jobs, products and services (Crane & Matten, 2007, p 41). Whilst business collapses affect society immensely and demands on organisational stakeholders are complex and challenging, only few business managers are formally educated in business ethics (Crane & Matten, 2007, p 41). This is probably the cause behind increasing compromises in modern day business. The use of business ethics helps shareholders and organisational managers in identification of problems and benefits that are associated with ethical issues and in the application of reason that takes account of principles, community needs and environmental concerns, along with the needs of immediate stakeholders (Crane & Matten, 2007, p 41).

Feminist ethics is concerned with issues like healthy social relationships, empathy, loving care and avoidance of harm (Clark, 2004, p 92). Feminist ethics looks at caring for one another being no less important than focus on profits. The discourse ethics theory concerns peaceful settlement of conflicts and is especially relevant in modern day organisations, where different stakeholders have divergent objectives (Clark, 2004, p 92).

The virtue ethics theory deals with goodness, moral excellence and good character. Virtue is considered to be a stage to act in a situation and not a mindless habit (Crane & Matten, 2007, p 46). It involves affective and intellectual aspects, both of which in combination involve doing right and virtuous acts, (a) on account of the right reason, and (b) to have positive feelings (Crane & Matten, 2007, p 46). Whilst virtue deals with morally positive behaviour, post modern ethics moves beyond the apparent value of morality and deals with inner feelings of specific situations (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 94). The post modern theory provides a holistic and rounded approach, wherein business organisations can either be driven by values or minimise their focus on them (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 94). The theory argues that minimising focus on values will inevitably lead to long term detriment and will work against the interests of all stakeholders (Abdullah & Valentine, 2009, p 94).

Conclusions

The review of various corporate governance theories reveals that financial success and enhancement of corporation value is undoubtedly a major objective of corporate governance and that the agency and stewardship theories work specifically towards reducing agency costs and improving shareholder benefits through enhancement of corporate value. It is however also evident that the phenomenal growth of corporations in recent decades and their assumption of a dominant and powerful presence in global society has numerous implications. The actions of corporations, as well as their demise, can affect societies in numerous ways.

Organisational shareholders, members of BODs, and managers, need to realise that sole focus on wealth maximisation and creation of shareholder benefits can have a range of negative repercussions that could harm both societies and organisations. Whilst it is necessary for modern day corporations to go beyond the needs of shareholders and assume responsibilities towards various stakeholders, it is also important to approach corporate governance with a holistic view and strive for the convergence of different theories in order to incorporate organisational sensitivity towards the discharging of different corporate responsibilities.

It is thus essential that the two main elements of business organisations, namely shareholders and managements, engage in constructive dialogue and discussion to implement corporate governance structures that go beyond the fixed mind-set of profit maximisation and incorporate issues like environmental concerns, human resource diversity and community benefits. It is evident from the discussion that good and effective corporate governance cannot be explained with the use of only one theory. It is appropriate in such circumstances to combine a range of theories that deal with the interests of different stakeholders and go beyond mechanical approaches to corporate governance.

References

Abdullah, H., & Valentine, B., 2009, “Fundamental and Ethics Theories of Corporate Governance”, Middle Eastern Finance and Economics, (4): pp. 88-94.

Alchian, A. A., & Demsetz, H., 1972, “Production, Information Costs and Economic Organization”, American Economic Review, Vol. 62: pp. 772-795.

Clark, T., 2004, Theories of Corporate Governance: The Philosophical Foundations of Corporate Governance, London and New York: Routledge.

Clarkson, M. B. E., 1995, “A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 1: pp. 92-117.

Crane, A., & Matten, D., 2007, “Business Ethics”, 2nd Edition, UK: Oxford University Press.

Daily, C.M., Dalton, D.R., & Canella, A.A., 2003, “Corporate Governance: Decades of Dialogue and Data”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 28 No. 3: pp. 371-382.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E., 1995, “The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence and Implications”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 1: pp. 65-91.

Donaldson, L., & Davis, J., 1991, “Stewardship Theory or Agency Theory: CEO Governance and Shareholder Returns”, Academy Of Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 1: pp. 65-78.

Eisenhardt, K.M., 1989, “Agency Theory: An Assessment and Review”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14: pp. 57-74.

Fama, E.F., 1980, “Agency Problems and the Theory of the Firm”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 88: pp. 288-307.

Freeman, R. E., 1984, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, Pitman: London.

Hillman, A.J., Canella, A.A., & Paetzold, R.L., 2000, “The Resource Dependency Role of Corporate Directors: Strategic Adaptation of Board Composition in Response to Environmental Change”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 37, No. 2: pp. 235-255.

Jensen, M.C., & Meckling, W., 1976, “Theory Of The Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs And Ownership Structure”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 3: pp.305-360.

Jensen, M.C., & Meckling, W. H., 1992, “Specific and General Knowledge and Organizational Structure”, in Werin, L., & Wijkander, H., eds., Contract Economics, Oxford: Blackwell.

Moldoveanu, M., & Martin, R., 2001, “Agency Theory and the Design of Efficient Governance Mechanisms”, Joint Committee on Corporate Governance, Available at: www.rotman.utoronto.ca/rogermartin/Agencytheory.pdf (accessed March 01, 2011).

Ross, S.A., 1973, “The Economic Theory of Agency: The Principal’s Problem”. The American Economic Review, Vol. 63, No. 2: pp. 134-139.

Rusconi, G., 2007, Stakeholder Theory and Business Economics, Available at: www.stthomas.edu/cathstudies/cst/…/Rusconi%20Final%20Paper.pdf (accessed March 01, 2011).

More From This Category

Inclusion of Networking for Women and Minority Group Members in the Workplace

Modern businesses continue to be dominated by men of the majority community, despite increasing entry of women and members of minority groups. Research has revealed that members of this group tend to, both intentionally and unintentionally interact with people of their own groups on account of homophilous reasons, thereby excluding access to women and members of ethnic minorities.

This results in considerable disadvantages for the excluded groups because network occurrences and dynamics often result in formal decisions for promotions, inclusion in new projects and giving of new responsibilities.

Insights on Management and Leadership

Management theory has come a long way, thanks to the hard work of many researchers and experts (DuBrin, 2009). A legendary management guru, Peter Drucker, summed up management as giving direction, providing leadership, and making smart decisions about resources (Drucker, 1994). Basically, it’s about getting things done and developing people along the way (DuBrin, 2009). In today’s business world, it’s all about putting the customer first and staying ahead of the competition. But that can sometimes lead to tough decisions about ethics and responsibility. This portfolio aims to help leaders and managers navigate these challenges while staying true to their values and commitments.

Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is truly one of the most puzzling aspects of today’s business world (Visser, 2008). It’s evolving rapidly, appearing to be both complex and yet somewhat unclear (Visser, 2008). Despite efforts from academic experts and management practitioners to define CSR, there’s still no universally accepted definition (Visser, 2008). The World Business Council for Sustainable Development takes a stab at it, defining CSR as: “the ethical behaviour of a company toward society; management acting responsibly in its relationship with other stakeholders who have a legitimate interest in the business. It’s the commitment by business to act ethically, contribute to economic development, and improve the quality of life of the workforce, their families, and the local community and society at large.” (Petcu et al., 2009, p. 4)

0 Comments