Communities of Practice in Knowledge Transfer

Published in 2016

Role of Communities of Practice in Knowledge Transfer and Creation Processes within Organisations.

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theorists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations (Baron & Tursting, 2005, P 3 to 72). Whilst business firms have traditionally relied upon expansion of scales, reduction of costs or spreading and penetration of markets as key methods for achieving competitive advantage, radical changes in the business environment in the last two decades have rendered such methods somewhat inadequate in the achievement of market and business leadership (Baron & Tursting, 2005, P 3 to 72).

The emergence and spread of globalisation, along with other contemporary phenomena like rapid advances in technology, instantaneous communication over enormous distances, the breakdown of economic and physical barriers between nations, the unrestricted transfer of thoughts and ideas, and the emergence of intensely competitive production facilities and huge markets in Asia have brought about a sea change in global business environments (Baron & Tursting, 2005, P 3 to 72). Intense competition has not just led to losses of thousands of jobs in Anglo American and West European businesses, but also driven home the need for adoption of new methods and processes of work, constant innovation and the harnessing and constructive use of knowledge (Baron & Tursting, 2005, P 3 to 72).

Management gurus like Peter Drucker and Michael Porter have constantly emphasised the need for organisations to build knowledge intensive cultures and encourage environments that foster constructive, lateral and innovative thinking (Lesser & Others, 2000, P 16 to 92). Most western and Japanese business corporations have responded to this need to establish and encourage knowledge environments by bringing in outside experts to transfer knowledge to organisational employees, radically improving in-house and external training facilities, enhancing internal communication, and fostering systems of mentoring (Lesser & Others, 2000, P 16 to 92). In addition to the adoption of such methods, techniques and processes, it is accepted by organisational and learning experts that most progressive and well managed business organisations have both explicit and tacit knowledge resources (Lesser & Others, 2000, P 16 to 92). Whilst explicit knowledge resources are represented by the various knowledge based systems and methods used by business organisations, as well as the formalised information and knowledge resources available in the company, (both through research and development functions and other avenues for knowledge determination), tacit knowledge consists of the various elements of knowledge that are available at different work force levels and are not incorporated in the organised and articulated knowledge structures of organisations (Lesser & Others, 2000, P 16 to 92). Such tacit knowledge refers to the internal thought processes, information, experience and collective knowledge that are stored inside the minds of employees (Brown & Duguid, 1991, P1). Explicit knowledge on the other hand includes knowledge sources like books and journals that are used by managers, the legal knowledge that is available with the company and even email directions that are passed on between superiors and subordinates (Brown & Duguid, 1991, P1). Knowledge management specifically aims at converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge and thereafter again into tacit knowledge in an ever growing cycle of expansion and regeneration (Hafeez & Alghatas, 2007, P 1 to 14). Called knowledge spirals by Nonaka and Takeuchi, such processes used to traditionally occur through informal and totally voluntary work groups who had particular knowledge, and are now being attempted in progressive organisations through the use of knowledge creating processes like Communities of Practice (Hafeez & Alghatas, 2007, P 1 to 14) (Nonaka & Nishiguchi, 2007, P1).

The last decade has seen an ever increasing utilisation of Communities of Practice (COP) to convert tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge and thereby aggressively accelerate knowledge expansion and utilisation within organisations (Hafeez & Alghatas, 2007, P 1 to 14). Whilst much of tacit knowledge in organisations traditionally used to exist beyond the working realm of organisations, and consequently remained unused and often lost when holders of such knowledge left their organisations, the aggressive conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge is enabling organisations to integrate such internally available knowledge in their formal knowledge resources, make far more effective use of them, and radically enhance their competitive advantage (Hafeez & Alghatas, 2007, P 1 to 14).

COPs are formed inside organisations by employees who engage in collective processes of learning and knowledge application in shared ways (Ashton, 2004, P 33 to 43). Such COPs are not created by the informal coming together of some employees from different departments for casual relaxation (Ashton, 2004, P 33 to 43). They are on the other hand characterised by the existence of shared domains, community activity and common practice (Ashton, 2004, P 33 to 43). Whilst COPs can occur in a range of forms, they have three compulsory elements, namely a community, a domain and a practice (Ashton, 2004, P 33 to 43). Although such human structures have existed for ages, (from the time when people have engaged in collective learning), their methodical use in business organisations is a comparatively recent phenomenon (Ashton, 2004, P 33 to 43). Whilst constant efforts have been made in recent years at institutionalising knowledge and enhancing organisational structures through the application of information systems, the results of such efforts have by and large been modest, if not disappointing (Ashton, 2004, P 33 to 43). COPs on the other hand are capable of being effectively adopted and used by business organisations because of their internal awareness of the criticality of knowledge and of the need for its strategic management (Hafeez & Alghatas, 2007, P 1 to 14). COPs, by focusing on people, the interaction between them, the reinforcement they provide to each other and the trust that is built up in a system by collective working provide a new and effective approach for building knowledge environments and enhancing knowledge spirals (Hafeez & Alghatas, 2007, P 1 to 14).

The use of COPs in business organisations enables members of communities, (operating in common domains and having shared purpose), to assume joint responsibility for deciding upon the required knowledge, obtaining it, giving it appropriate structure and thereafter for managing such communities; this helps in the construction of a direct relationship between the obtaining of knowledge and its practical application, because of the communality of people who take part in COPs and in specific teams and particular business units (Nonaka & Nishiguchi, 2007, P1). The participants of COPs are uniquely empowered to deal with the tacit, the explicit and the dynamic features of knowledge construction and the meshing of knowledge from different sources into larger and far more organisationally effective knowledge structures (Wenger, 2006, P 1). COPs in business organisations are commonly formed by people across departmental and geographical limitations and in international organisations can comprise of people from different areas of the world (Wenger, 2006, P 1). The cross fertilisation of knowledge from such an array of sources can lead to knowledge inputs that would have been unimaginable even a couple of decades ago and can help in the development of immensely fruitful knowledge structures (Wenger, 2006, P 1).

Business surveys reveal the effectiveness of COPs in converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge (Hafeez & Alghatas, 2007, P 1 to 14). In fact surveys reveal that the overwhelming majority (95%) of Best Practice companies in the United States think of COPs as critically integral to their knowledge management strategies (Hafeez & Alghatas, 2007, P 1 to 14). Whilst such feelings are explicitly pronounced in the case of consulting firms like Ernst and Young, COPs are now playing significant roles across the spectrum of manufacturing and service organisations (Hafeez & Alghatas, 2007, P 1 to 14). Microsoft for example constantly encourages both creativity and structure. The fundamental elements of their strategy comprise of constantly synchronising the individual work of employees, along with their work in teams, and to regularly stabilise developing features of projects through formal specifications.

Whilst there is widespread agreement on the role of COPs in knowledge construction within organisations, much of the success of such communities depends upon the development of familiarity and reciprocal belief and trust between COP members. Such familiarity and trust does not occur just by the assignment of roles and its absence often renders the performance of COPs inadequate, by restricting the sharing and application of tacit knowledge. Organisations need to be very careful in the construction and nurturing of COPs, if they are to be used as effective tools for development and creation of knowledge.

Role of Managers in Facilitating the Creation and Development of a Community of Practice

Whilst the role of COPs in the construction of organisational knowledge, and in the meshing of tacit and explicit knowledge into a knowledge spiral, is widely accepted, managers understand that such communities do not spring up on their own but need to be promoted, encouraged, fostered and monitored for them to help in creation of knowledge (Baron & Tursting, 2005, P 3 to 72).

The aim of a knowledge management scheme by and large concerns the extraction and utilisation of the knowledge that exists in employees, and to use the organisational infrastructure to apply them in value adding processes. Knowledge transfers occur when knowledge moves between employees, and such movement is succeeded by the construction of a process or act for the utilisation of such acquired knowledge. Whilst knowledge management processes aim to encourage and control such critical occurrences and address such junctures, the use of COPs for this purpose may be inadequate in certain cases.

Contemporary research reveals that creation of knowledge depends upon the fruitful interaction between participants within COPs, a process that can be adversely effected by issues like lack of trust between employees, or the tendency of employees to hold on to their knowledge on account of different psychological reasons. Whilst construction of knowledge can be hindered by the disinclination of participants of COPs to share their tacit knowledge, knowledge creation can also be adversely effected by the inability or unwillingness of participants to accept and utilise such knowledge. The commonly held belief that information and knowledge when provided to employees leads to further interaction in the knowledge realm and the generation of further knowledge could be without solid foundation. Although knowledge management strategies that use COPs aim to procure the knowledge available within individuals, and thereafter leverage such knowledge within the COP, recent surveys conclude that such strategies could adversely affect the knowledge capabilities of organisations by restricting knowledge formation to employees within COPs, thereby denying the gains of such actions to sponsoring organisations.

With the interaction of knowledge between COP participants being influenced by opposing forces like motivation and trust, the play of such factors leads to the determination of knowledge and its transfer beyond the COP for continuation in traditional organisation channels. Many COPs end up with disappointing results, not just because of lack of trust, motivation and participation, but also because of inadequacy of transparency and deficiency in commonality of purpose and context. In such cases participants of the COP could well desert newly constructed communities and go back to their previously existing informative, but yet unproductive, networks.

Managers play critical roles in the construction, growth, and productivity of successful COPs. The effectiveness of COPs can be adversely influenced by a range of reasons. Employees who have information could for example have to go away from the office, thus postponing successful outcomes by many days. Managers contribute in many ways to ensure the effective formation and working of such communities; in fact researchers and COP experts assert that managers can radically improve the effectiveness of COPs because of their organisational knowledge and authority, as well as their interest in utilising all internally available information for organisational benefit.

Managers play very important roles in the development of relationships between people within organisations. Whilst their actions can very easily lead to the development of mistrust and resentment between employees, their behaviour can also help in building trust between COP participants, constructing of communities with care and in ensuring that members have communality of domain and purpose. Trust and faith between COP members can be enhanced through repeated and effective communication about organisational objectives and the relevance of COPs in constructing organisational knowledge and in sharpening of organisational competitive advantage (Ashton, 2004, P 33 to 43).

The managers of Rabobank Australia and New Zealand have in recent years introduced COP projects that enable the bank to, (a) decrease the learning curves of new entrance, (b) respond swiftly to needs and enquires of customers, (c) reduce rework and prevent time wastage on reinventing known processes and (d) generating new product and service ideas (Hinton, 2003, P 1 to 15).

Whilst COP success depends significantly upon the structure and cohesion of communities, they also require basic tools such as office intranet systems, which enable lateral communication by employees through the introduction of processes for facilitation of user generated contempt (Nonaka & Nishiguchi, 2007, P1). The construction of portals for all the user generated content of organisations, as well as the introduction and optimisation of technologies for integrated search can lead to the construction of networks that can bring together everything that employees need to do their jobs.

Theorists believe the motion of practice to be critical to COPs success. Pointing out that group effectiveness emerges only through practice of craft, experts state that managers can play an important role in encouraging the application of knowledge gained and created in COP surroundings through the facilitation and integration of generated knowledge into actual work processes by constructing responsive organisational systems. The formation of intra departmental COPs is also dependent upon the openness and encouragement of managers.

As such whilst communities of practice can be very effective vehicles of knowledge transfer and creation, their optimisation and success depends inordinately on the encouragement provided by managers and the extent of support given by them to the COP process. Their role in the success of COPs is immense and essential for achievement of organisational COP strategy.

References

Ashton, D. N, (2004), the impact of organisational structure and practices on learning in the workplace, International Journal of Training and Development, 8(1), P 43–53

Barton. T & Tursting, T, (2005), Beyond Communities of Practice: Language Power and Social Context, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83643-2

Brown, J.S & Duguid, P, (1991) Organizational learning and communities-of-practice Retrieved December 23, 2009 from en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Community_of_practice

Hafeez, K & Alghatas, F, (2007) Knowledge Management in a Virtual Community of Practice using Discourse Analysis, The Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 5, 1, P 29 – 42, available online at www.ejkm.com

Hinton, B, (2003), Knowledge Management and Communities of Practice: an experience from Rabobank Australia and New Zealand, International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 5,3, P 1 to 15

Hughes, J, N. Jewson, & Unwin. L, (2006), Communities of practice: critical perspectives, Routledge

Lesser, E. L, Fontaine, M. A, & J.A. Slusher, J.A, (2000) Knowledge and Communities, Butterworth-Heinemann

Nonaka, I & Nishiguchi, T, (2007), Knowledge creation in Organisations, Retrieved December 23, 2009 from tihane.wordpress.com/…/knowledge-creation-in-organisations

Sharp, J, (1997) Communities of Practice: A Review of the Literature Retrieved December 23, 2009 from www.tfriend.com/cop-lit.htm

Wenger, E, (2006), Communities of practice, Retrieved December 23, 2009 from www.ewenger.com/research

Wenger, E, & George, P, (2004), Communities of Practice and Community-enabled Strategic Results from Self-Organisation, Retrieved December 23, 2009 from www.co-i-l.com/coil/knowledge-garden/cop/index.shtml

Wenger, E.C, & Snyder, S.M, (2000), Communities of Practice: The Organizational Frontier Retrieved December 23, 2009 from hbswk.hbs.edu/archive

Wenger, E, McDermott, R & Snyder, W, (2002) Cultivating communities of practice: a guide to managing knowledge, Harvard Business School Press

Wenger, E, (2002), Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity (Cambridge University Press)

More From This Category

Innovation & Change are Central to Value Creation

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theoInnovation, as a concept, has been examined and developed over time, which, in turn, has resulted in the creation of several definitions. Innovation entails the conversion of an idea into a solution that results in addition to value from the perspectives of customers. Customers are unlikely to change their buying behaviour if an innovative product does not result in value addition for them. Innovation involves the application of useful and novel ideas; creativity comprises the seed of innovation but is likely to remain in the realm of idea generation until and unless it is applied and scaled suitably).

Organisational change constitutes the process of alteration of organisational strategies, processes, procedures, technologies, and culture.rists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

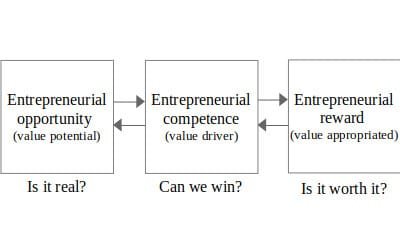

Theories of Entrepreneurial Opportunity

The study of entrepreneurship isn’t just about admiring successful entrepreneurs from afar. It’s about digging deep into why they do what they do, when they do it, and how it all plays out in the end. It’s like peeling back the layers of an onion to uncover the juicy bits inside.

And to tackle these burning questions, we’ve got two heavyweights in the ring: the Discovery Theory and the Creation Theory. These bad boys are all about figuring out why humans do what they do and how it helps them achieve their goals.

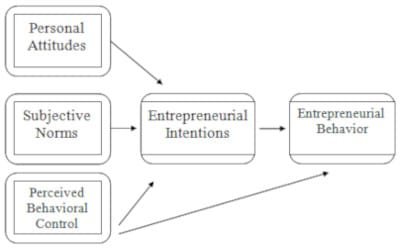

Behavioural Theories and Entrepreneurship

Management and behavioural experts have delved into entrepreneurship extensively, and there’s a whole body of work on the topic. Lazear paints a broad picture, defining an entrepreneur as someone who starts a new venture. But that definition lumps together someone opening a small local business with giants like Jeff Bezos or Steve Jobs. Sure, there’s some truth there, but it’s tricky to draw general conclusions about entrepreneurship because it comes in so many shapes and sizes. Entrepreneurship research tackles big questions like why some people dive into entrepreneurial ventures while others with similar talents and energy don’t, and why some spot entrepreneurial opportunities while others miss them.

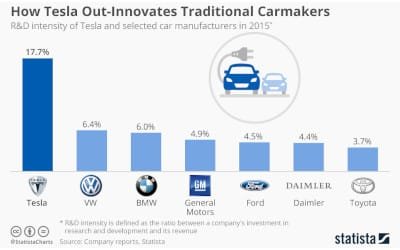

Tesla: Critical Evaluation of Corporate Social Responsibility and Global Innovation Management

Established in 2003, Tesla Motors, the US-headquartered manufacturer of electric vehicles, solar panels and solar roof tiles, has become globally famous for its pioneering, innovative and entrepreneurial efforts in the development of electric vehicles and renewable energy. The firm has grown phenomenally in the last two decades and is now one of the most valuable corporations in the world. Its CEO Elon Musk is currently one of the the wealthiest persons in the world

Competitive Advantage through the Learning Organisation

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theorists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

A Unique Entrepreneurial Path: Sir Richard Branson

This short report aims to analyse the area of entrepreneurship, with specific reference to the entrepreneurial abilities, skills, and success of Sir Richard Branson.

0 Comments