Innovation and Product Development in the Manufacturing Industry

Introduction

This report deals with the selection of a specific contemporary product that can be termed to be innovative in nature, followed by the analysis of the various challenges faced by the concerned organisation in marketing and commercialising it, as well as the evaluation of a range of solutions that can be used to overcome these challenges.

Innovation can be understood as the process for the successful introduction of something new and useful and in the organisational context, something that can be converted for the achievement, maintenance and furtherance of competitive advantage (Burcharth & Ulhoi, 2011, p 119). Joseph Schumpeter has classified innovation into various segments, the first of which is concerned with the introduction of new products or the development of qualitative change in existing products (Burcharth & Ulhoi, 2011, p 119). The importance of innovation has been stressed time and again by various management and strategic experts like Peter Drucker and Michael Porter (Burcharth & Ulhoi, 2011, p 119).

Peter Drucker stated that innovation was change that created new dimensions of performance. An innovation, to be effective, had to be simple and focused; to be successful an innovation aimed at leadership within a given market or industry (Stanleigh, 2014, p 1). Michael Porter stated that innovation was essential for organisational survival and growth and was critical for the development of organisational value (Mobbs, 2010, p 1).

This report deals with the agricultural drones, which has recently been developed by HoneyComb, an Oregon, USA, based firm that that is engaged in the production and sale of products and services for enhancement of precession agriculture and forestry. This structured report first provides a brief description of the product and why it can be termed to be innovative in nature. It thereafter focuses upon the challenges likely to be encountered by the company in commercialising the product and the evaluation of diverse solutions that can be used for overcoming such challenges.

Choice of Product

A drone is an unmanned aerial vehicle that is either controlled by a “Pilot from the ground or autonomously by a pre-programmed instruction” (Green, 2013, p 1). Whilst drones have until now been primarily introduced for military purposes, either for surveillance or for armed action, contemporary technologically advanced firms are using them for various other services. Amazon for instance is seriously developing drones to deliver small parcels within specific geographical perimeters (Capgemini Consulting, 2014). Some organisations have started using agricultural drones for crop surveillance (Capgemini Consulting, 2014). The use of drones for surveillance can result in enhanced yields through crop health imaging and facilitation of agricultural action for crop enhancement (Precession Drone, 2014, p 1). HoneyComb, an Oregon based company produces agricultural drones, which have the following features (HoneyComb, 2015, p 1).

- Composite exoskeleton made from fibre

- Airframe design that ensures performance and stability in flight under challenging conditions

- Dual cameras that help in gathering information by capturing high definition visible and NIR imagery

- Hand launching facilities that allow flexible deployment and do not require cumbersome launch equipment.

- Capable of capturing data that can be processed into useful information.

Ryan Jansen stated that agriculture was expected to be the largest adopter of drone technology (Amato, 2014, p 1). He stated that his company focused on providing agricultural solutions with single autonomous fixed-wing drones and their extensive suits of cameras, sensors, analytics and mobile controllers (Amato, 2014, p 1).

Product innovation can be defined as the development of new products or changes in the design of established products or the utilisation of new materials or components in the manufacture of existing products (Trott, 2011, p 34). Product innovation results in the development, marketing and introduction of a new, redesigned or substantially improved good product or service (Conway & Steward, 2006, p 46). It can include a new product invention, technical changes or quality enhancements to an existing product (Cankurtaran et al., 2013, p 7). An innovative product is furthermore associated with the enhancement of the satisfaction of users and the enhancement of sales, profitability and competitive advantage of the manufacturer (Tidd, 2009, p, 72; De Paz et al., 2009, p 21).

Whilst drone technology is not exactly new and has been developed and sophisticated for military use for some years, HoneyComb and other organisations have been adapting the drone for extremely useful functions in agricultural surveillance (Honeycomb, 2015, p 1). The use of drones is very clearly the latest technological innovation in the agricultural sector (Grassi, 2015, p 1). With many agricultural operations spanning large geographical areas with low populations, drones can help farmers in enhancing the surveillance of their crops and in enhancing their agricultural output (Precision Drone, 2014, p 1). Farmers have until now monitored their operations by physical inspection either on the ground or through manned aerial flights or satellites (UFarm, 2014, p 1). The use of drones can help farmers in gathering data that was previously inaccessible and make changes during the growing season (Farms.com, 2013, p 1). The data gathered from drones can be used for enhancing yields, applying fertiliser, water and chemicals only when and where they are needed, mapping of fields, monitoring of crop health, checking for signs of disease and saving time in the process (Green, 2013, p 1).

It is evident that the utility of drones for farmers across countries and continents can result in significant demand for technically sophisticated and reliable products that can generate data quickly, safely and efficiently (The Globe and Mail, 2013, p 1). It is also important to understand that the specific characteristics of drones are increasing their utility in different areas like surveillance and delivery (Precision Drone, 2014, p 1). Amazon, the global retailing organisation, for example, is working strongly on the development of drones that can be used for delivering books and small products to customers within specific geographical boundaries (Capgemini Consulting, 2014). There is little doubt the HoneyComb’s drones can be termed to be innovative products with regard to the newness in their product qualities, their utility for users and their commercial potential for the firm (Grassi, 2015, p 1).

Commercial, Business and Environmental Challenges

HoneyComb has developed significantly innovative products in the area of agricultural drones and aims to commercialise the product and achieve market success through the satisfaction of increasing numbers of agricultural clients (Precision Drone, 2014, p 1). It is important however to appreciate that the organisation is likely to face several types of challenges, both in its internal and external organisational environment in the process of achieving commercial success in this area, both over the short and medium-term (Grassi, 2015, p 1). Several organisations are entering the area of aerial surveillance with parallel products (Grassi, 2015, p 1). The actual needs of farmers and other users of agricultural drones is also likely to evolve and change with time (Green, 2013, p 1). This section details the different types of challenges likely to be faced by HoneyComb in its pursuit of success in innovation, both in the short and the medium term.

Modern-day organisations have to face significant challenges in the introduction and commercialisation of innovative products (Shavinina, 2003, p 196). Many organisations find it extremely difficult to successfully manage their innovations, when it comes through breakthroughs, even the most innovative organisations face significant and diverse challenges, which can range from struggling with the ambiguous, unclear and fuzzy frontend of the innovation process to the identification and prioritisation of opportunities and moving concepts and ideas through the pipeline (Tidd, 2009, p 56). Experts on innovation recognise that companies do not enjoy specific magic formulas for success (Tidd, 2009, p 59).

Most organisations recognise that the development and introduction of new products and services are likely to provide them with the lifeblood of the future and the importance of maintaining products and service concepts that include line extensions and breakthroughs (Jain et al., 2010, p 21). The challenge in this case is formidable and includes the extension of existing products in order to enhance and maximise their contribution throughout their lifecycle whilst simultaneously introducing new offerings that have the potential to cannibalise existing products or develop new growth categories (Shavinina, 2003, p 196). Regardless of the industry, many organisations thus face common challenges associated with driving new products, the more important of which are the identification of promising opportunity areas, the prioritisation and selection of most promising opportunities, the championing and defending of fragile ideas throughout the innovation process and building the organisational alignment necessary for successful commercialisation (Van de Ven et al., 1999, p 34). It is important to appreciate, in this context, that sustained and effective innovation continues to be one of the greatest challenges facing most US and UK based companies (Trott, 2011, p 49). Research has also revealed that firms by and large fail in the introduction of innovative products most of the time (Mobbs, 2010, p 1). Keeley found that average firms are successful in the development of innovative products only 4% of the time (Derkhopf, 2009, p 1). Research into the reasons behind such failures in innovation have resulted in the development of three categories of causes for such failure, namely (a) cultural and organisational barriers to innovation, (b) strategic and market related challenges to innovation and (c) process type barriers to innovation (Zahra & George, 2002, p 187).

Several experts have attributed lack of success in the introduction and commercialization of innovative products to corporate culture. Cohen and Levinthal (1990, p 132) stated that innovation was not integral to the culture of many firms. Such cultural issues directly affected the actions of the individuals responsible for driving innovation forward (Smith, 2010, p 63). The concept of culture, amongst other issues, being important for the introduction, assimilation, and use of new knowledge within firms is known as the theory of “absorptive capacity” (Zahra & George, 2002, p 185).

Many academics and practitioners have also declared that firms are not designed and structured for effective innovation activity (Tidd et al., 2005, p 107). It has for instance been stated that organisational attributes like hierarchical structures, top-down command and lack of vertical and horizontal communication can result in inflexibility in change management as also in responding to new technical and market opportunities (Tidd et al., 2005, p 107). Organisational rigidity can prevent firms from moving to next-generation business paradigms (Saleh & Wang, 1993, p 16). It has also been argued that several firms lack the organisational dualism that assists in the achievement of effectiveness in core businesses with the innovation required for new business development (Saleh & Wang, 1993, p 16).

The development and entrenchment of organisational silos for the achievement of efficiencies in the execution of immediate activities has also been attributed to be a main cause in impeding innovation; such development of silos, experts like Zahra & George (2002, p 187) have declared, obstructs sharing of knowledge and technology between groups, which is frequently required for new product or service innovation. It has also been suggested that several firms are structured in ways that facilitate obstruction of individual independence and experimentation and stop employees from furthering work in innovative projects (Rogers, 2003, p 87).

The presence of strategic and marketing associated barriers can also impede successful innovation. Several experts have posited that an organisation’s perception of its mission and purpose, its strategic intent and market focus, as also its strategic choice and intent can result in be self-limitation and hamper innovative activity (Stanleigh, 2014, p 1). Van de Ven et al., (1999, p 37) stated that organisational leaders often became so strategically focused on satisfying the requirements of important customers that they were unable to focus their pay attention on innovation in order to satisfy the needs of new market entrants. This phenomenon is also known as “milking the cow for too long” (Van de Ven et al., 1999, p 38). It has also been found that organisational managements often fail to appreciate and recognise the relationship between strategic intent and the capabilities of their firms in areas of adaptation and absorption as also the requirement to focus and stress on these capabilities (Shavinina, 2003, p 196).

Success in achievement of innovation at … can also be impeded by diverse process-related barriers to innovation. Innovation processes and their probability in impeding or enhancing innovation success have focussed upon by academics and experts for some years (Tidd, 2009, p 59). It has for example been found that many organisations focus on processes for the development of new products but fail to pay significant attention to other characteristics of innovation like innovation in services or business model (Tidd, 2009, p 59). It is also being questioned whether the use of formalised innovation processes, such as the stage-gate system, have in fact assisted or impeded commercial success in innovation (Utterback, 1994, p 11).

Several researchers have also stressed upon the methods for illuminating the “fuzzy front end” of the development of new products (Utterback, 1994, p 11). The failure to understand the needs of customers adequately, both present and future, has often been cited to be a major roadblock to innovation (Utterback, 1994, p 11).

Available Solutions

The organisational management of HoneyComb is as of now significantly optimistic about its prospects (Amato, 2014, p 1). The CEO of the company Ryan Jensen felt that the organisation could master this niche market when the demand for the product went beyond tipping point (Amato, 2014, p 1).

“Agriculture is expected to be the largest adopter of drone technology,” Jenson told DRONELIFE in an email. “Given the impact that drone technology has already had in agriculture, we believe many farms across the country, and the world, will adopt the technology as a standard tool in their operations.” (Amato, 2014, p 1)

It is important however for the organisation to take specific action to ensure success in initial implementation and in the future (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990, p 134). It is important for the organisation to primarily focus upon the development of an organisational culture that supports and drives innovation (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990, p 134). The organisational management should as such focus upon the creation of a powerful context for innovation and paint a picture of what the organisation will look like after the success of the innovation and after innovation becomes a way of life (Capgemini Consulting, 2014, p 4). It is also important for the organisational management to help people learn to think differently, link individual effort to the big picture, build and encourage diversity, use supportive language and behaviour and acknowledge and reward innovation (Crane & Meyer, 2011, p 4). Whilst the organisation as of now is small and has an employee strength of about 20 people, there is little doubt that organisational strength will have to be enhanced significantly in the coming months to ensure organisational expansion and growth (Crane & Meyer, 2011, p 4). It is thus important for the management of the company to build and encourage diversity in the workforce (Godin, 2008, p 1-3). Researchers have found that innovative tendencies can be killed when all organisational employees think and make decisions in the same way and tend to avoid conflict (Godin, 2008, p 1-3). It is also important for employees to understand the criticality of innovation to the organisation and the ways in which their work fits into the overall effort (Capgemini Consulting, 2014, p 4). Such information must be followed up by providing employees with continuous feedback on the results of their efforts, their public recognition and appropriate rewards (Capgemini Consulting, 2014, p 4). Martins and Martins (2002, p 58) stated that organisational managements should develop a comprehensive approach to the development of an organisational culture that truly supports innovation (Gallouj & Djellal, 2010, p 76). They developed an organisational cultural matrix that was based upon the work of Edgar Schein and drove upon open systems theory (Smith, 2010, p 93). Their model explained the interaction between various organisational subsystems, associated with goals, management, structures, technology and psycho-sociological factors and the complex interaction that took place on different levels between groups and individuals, as also with other organisations and the external environment (Gallouj & Djellal, 2010, p 76). The model developed by Martins and Martins (2002) is detailed below.

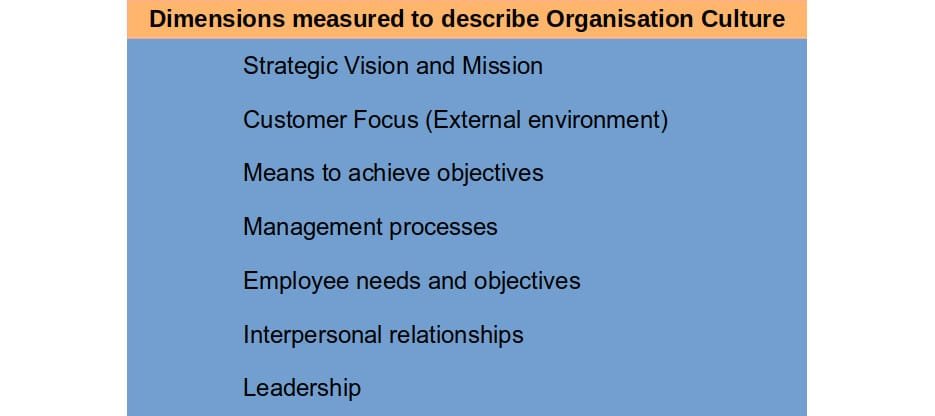

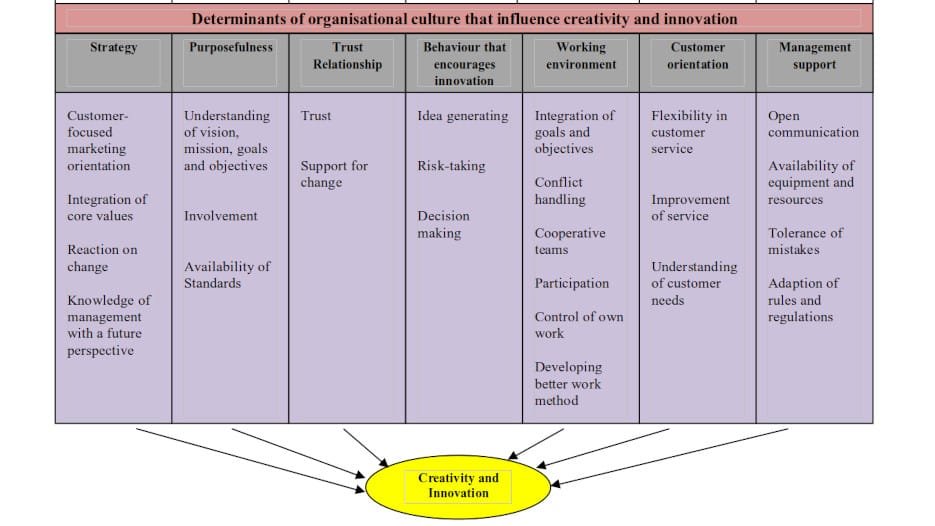

Figure 1: Model of the Influence of Organisational Culture on Creativity and Innovation(Source: Martins & Martins, 2002, p 62)

It is important for organisations to ensure that their organisational strategy is customer-focused, marketing oriented, responsive to change and endowed with a future perspective (Smith, 2010, p 93). The organisational management must furthermore be clear in its purpose and in its understanding of organisational vision, mission, goals and objectives (Hart & Christensen, 2002, p 52). The organisational management of HoneyComb must for this purpose develop organisational purpose through the creation of standards in the diverse areas of product quality (Hart & Christensen, 2002, p 52). The availability of measurable standards for individual achievement appears to play a role in the creation of purposefulness, creativity and innovation (De Paz et al., 2009, p 57). It is also important for the management of HoneyComb to specifically focus upon behaviour that encourages innovation, the development of a supportive working environment and high levels of customer orientation through the enhancement of understanding of consumer needs, enhancement in consumer service and achievement of flexibility in consumer service (Burcharth & Ulhoi, 2011, p 118).

It is in this context important to examine the innovative practices followed by highly innovative organisations like Google, which follow up the development of innovative ideas with their successful implementation in the marketplace (He, 2013, p 1). Google’s important approaches towards innovation are detailed below.

- Ideas come from everywhere: Google has an internal list where people can post new ideas and everyone can go and see them. This is indicative of a conducive working environment, strong management support and a relationship of organisational trust (Salter, 2008, p 1).

- Share whatever you can: Every idea, project and deadline is accessible to all Google employees on the Internet. With so much information being sharedshared, employees have insight into what’s happening and what’s important. This is indicative of behaviour that encourages innovation, purposefulness, working environment and management support (Salter, 2008, p 1).

- Hire not just the best but the most brilliant: Google constantly attempts to hire the best possible people in order to enhance customer orientation, idea generation, risk-taking and decision making processes (Salter, 2008, p 1).

- Licence to pursue dreams: Employees get one day a week to pursue their interests. Approximately 50% of Google’s new product launches come from this time. This in indicative of behaviour that encourages idea generation and risk-taking (Salter, 2008, p 1).

- Focus on data, not politics: This is indicative of an encouraging working environment that is indicative of cooperation, participation and conflict management (Salter, 2008, p 1).

- Creativity loves restraint: Employees in Google are provided with a vision, deadline and rules about getting there. Whilst creativity is perceived to be an unbridled issue, engineers are able to manage constraints. This organisational aspect is indicative of customer focus, availability of standards and adaptation of rules and regulations (Salter, 2008, p 1).

- Worry about usage and users, not money: Google focuses upon the development of innovations that are easy to use and attractive. This is in line with Drucker’s theory about the best innovations essentially being the most simple ones. This feature is indicative of understanding of consumer needs and the development of attractive products (Salter, 2008, p 1).

- Don’t kill projects. Morph them: Google feels that projects should not be killed if it is not felt to be good enough to be commercialised. It should be examined for its positive aspects, which can be used elsewhere (Salter, 2008, p 1).

The analysis of available theory on achievement of success in innovation and the study of Google’s organisational practices reveal that whilst HoneyComb may be a small company and likely to face significant challenges in its quest for successfully implementing and commercialising its innovative product, namely a specialised agricultural drone that can help farmers significantly in enhancing their yields by providing them with substantial and previously inaccessible information on their crops and their farming practices, the organisation can achieve success by focusing upon specific issues (Conway & Steward, 2006, p 114). It must very clearly focus upon two distinct areas, the understanding of customer needs in totality and the development of organisational features that encourage the continuous pursuit of innovation in a practical, sustainable and implementable manner. The organisational management should in this context try to understand consumer needs both in areas of product characteristics and capabilities and service, along with competitive offerings. It should furthermore try to anticipate customer needs as they evolve and try to satisfy them through the development of innovative product features and enhanced service (Burcharth & Ulhoi, 2011, p 118). The management of the company must additionally focus in a single-minded way on the development of an innovative organisation with complementary elements (Tidd, 2009, p 89). The organisational strategy, whilst being customer-focused and marketing-oriented should result in purposefulness by way of clarity in goals and objectives and development of product standards (Godin, 2005, p 2). The organisational management must furthermore be open to communication, make equipment and resources available, be tolerant of mistakes and adopt rules and regulations for achievement of customer satisfaction (Conway & Steward, 2006, p 114). The organisational culture must as such be focused upon trust, idea generation, decision making, integration of goals and activities, conflict management, participation and development of better working methods, the dovetailing of these various features will inevitably help in the development of diverse organisational capabilities that will drive success in generation and implementation of innovation (Jain et al., 2010, p 38).

Conclusion

This report focuses upon the ways in which a specific innovative product should be handled for achievement of market success. The product chosen for this purpose is an agricultural drone, recently developed by HoneyComb, an Oregon based technological firm. The conduct of the study carried out for this report revealed that whilst innovation continues to be an immensely challenging process characterised by low levels of success, the adoption of some specific approaches, both within the organisation and externally for the understanding and satisfaction of customer needs can help significantly in enhancing the chances of innovation success. The management of HoneyComb would be well advised to pay attention to these internal and external aspects in order to achieve continuing organisation success with their innovative product.

References

Amato, A., (2014), “HoneyComb and the AgDrone”, Available at: http://dronelife.com/2014/04/07/honeycomb-and-the-agdrone/ (accessed January 25, 2015).

Burcharth A., & Ulhoi, J., (2011), “Structural approaches to organizing for radical innovation in established firms”, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Vol. 12, Iss (2): pp. 117-126.

Cankurtaran, P., Langerak, F., & Griffin, A., (2013), “Consequences of New Product Development Speed: A Meta‐Analysis”, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol.30, Iss (3): pp. 1-22.

Capgemini Consulting, (2014), “Facing Innovation Challenges: How digital technologies can improve your innovation and lifecycle performance”, Available at: http://www.de.capgemini-consulting.com/resource-file-access/resource/pdf/facing-innovation-challenges.pdf (accessed January 25, 2015).

Cohen, W., & Levinthal, D., (1990), “Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 35, Iss (1): pp. 128-152.

Conway, S., & Steward, F., (2006), Managing Innovation, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crane, G.F., & Meyer, H.M., (2011), “The Challenges of Innovation in American Companies: An Executive Ethnographic Investigation”, Journal of technology management & innovation, Vol. 6, Iss (4): pp. 1-10.

De Paz, C. M., Rebentisch, E., & Gupta, N., (2009), The Path to Developing Successful New Products, NY: MIT Sloan Management Review Press.

Derkhopf, C., (2009), “Larry Keeley: “Innovation Summit, Chicago 2009″, Available at: http://www.business-designers.com/larry-keeley-2009-innovation-summit-chicago/ (accessed January 25, 2015).

Farms.com, (2013), “Economic impact of drones in Agriculture”, Available at: http://www.farms.com/news/economic-impact-of-drones-in-ag-in-kansas-70261.aspx (accessed January 25, 2015).

Gallouj, F., & Djellal, F., (2010), The Handbook of Innovation and Services, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Godin, B., (2005), “The Linear Model of Innovation: The Historical Construction of an Analytical Framework“, Available at: http://www.csiic.ca/PDF/Godin_30.pdf (accessed November 27, 2011).

Godin, B., (2008), “In the Shadow of Schumpeter: W. Rupert Maclaurin and the study of Technological Innovation”, Project on the Intellectual History of Innovation, Available at: www.csiic.ca/PDF/IntellectualNo2.pdf (accessed February 27, 2013).

Grassi, M., (2015), “Drones On The Farm In 2015: Dark Days Ahead”, Available at: http://dronelife.com/2015/01/06/drones-farm-2015-dark-days-ahead/ (accessed January 25, 2015).

Green, M., (2013), “Unmanned Drones May Have Their Greatest Impact on Agriculture”, Available at: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/03/26/unmanned-drones-may-have-their-greatest-impact-on-agriculture.html (accessed January 25, 2015).

Hart, S. L., & Christensen, C. M., (2002), “The great leap: Driving innovation from the base of the pyramid”, MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 44, Iss (1): pp. 51-56.

He, L., (2013), “Google’s Secrets Of Innovation: Empowering Its Employees”, Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/laurahe/2013/03/29/googles-secrets-of-innovation-empowering-its-employees/ (accessed January 25, 2015).

HoneyComb, (2015), “About Us”, Available at: http://www.honeycombcorp.com/about/ (accessed January 25, 2015).

Jain, R., Triandis, C.H., & Weick, W.C., (2010), Managing Research, Development and Innovation: Managing the Unmanageable, 3rd Edition, NY: Wiley.

Martins, E., & Martins, N., (2002), “An Organisational Culture Model to Promote Creativity and Innovation”, SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, Vol. 28, Iss (4): pp. 58-65.

Mobbs, C.W., (2010), “Why is Innovation Important”, Available at: http://www.innovationforgrowth.co.uk/whyisinnovationimportant.pdf (accessed January 25, 2015).

Precession Drone, (2014), “Drones For Agricultural Crop Surveillance”, Available at: http://www.precisiondrone.com/agriculture/ (accessed January 25, 2015).

Rogers, E. M., (2003), Diffusion of Innovations, 5th edition, New York: Free Press.

Saleh, S.D., & Wang, C.K., (1993), “The management of innovation: Strategy, structure and organisational climate”, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. 40, Iss (1): pp. 14–21.

Salter, C., (2008), “Marissa Mayer’s 9 Principles of Innovation”, Available at: http://www.fastcompany.com/702926/marissa-mayers-9-principles-innovation (accessed January 25, 2015).

Shavinina, L., (2003), The International Handbook on Innovation, Elsevier: Oxford.

Smith, D., (2010), Exploring Innovation, 2nd edition, NY: McGraw Hill.

Stanleigh, M., (2014), “Create a New Dimension of Performance with Innovation”, Available at: http://www.bia.ca/articles/CreateaNewDimensionofPerformancewithInnovation.htm (accessed January 25, 2015).

Tidd, J., (2009), Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change, 4th Edition, NY: Wiley.

Tidd, J., Bessant, J., & Pavitt, K., (2005), Managing Innovation: Integrating technological, market and organizational change, Third edition, NY: Wiley.

The Globe and Mail, (2013), “Drones take to the agricultural skies”, Available at: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/partners/ge-innovation/drones-take-to-the-agricultural-skies/article20233125/ (accessed January 25, 2015).

Trott, P., (2011), Innovation Management and New Product Development, 5th Edition, NJ: Pearson Publishers.

UFarm, (2014), “What Benefits Can Agricultural Drones Offer Landowners?”, Available at: http://ufarm.com/benefits-can-agricultural-drones-offer-landowners/ (accessed January 25, 2015).

Utterback, J.M., (1994), Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation: How Companies Can Seize Opportunities in the Face of Technological Change, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Van de Ven, A., Polley, D.E., Garud, R. & Venkataraman, S., (1999), The Innovation Journey, New York: Oxford University Press.

Zahra, S., & George, G., (2002), “Absorptive capacity: A review, re-conceptualization, and extension”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 27, Iss (2): pp.185-203.

More From This Category

Innovation & Change are Central to Value Creation

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theoInnovation, as a concept, has been examined and developed over time, which, in turn, has resulted in the creation of several definitions. Innovation entails the conversion of an idea into a solution that results in addition to value from the perspectives of customers. Customers are unlikely to change their buying behaviour if an innovative product does not result in value addition for them. Innovation involves the application of useful and novel ideas; creativity comprises the seed of innovation but is likely to remain in the realm of idea generation until and unless it is applied and scaled suitably).

Organisational change constitutes the process of alteration of organisational strategies, processes, procedures, technologies, and culture.rists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

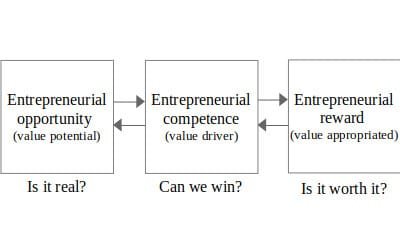

Theories of Entrepreneurial Opportunity

The study of entrepreneurship isn’t just about admiring successful entrepreneurs from afar. It’s about digging deep into why they do what they do, when they do it, and how it all plays out in the end. It’s like peeling back the layers of an onion to uncover the juicy bits inside.

And to tackle these burning questions, we’ve got two heavyweights in the ring: the Discovery Theory and the Creation Theory. These bad boys are all about figuring out why humans do what they do and how it helps them achieve their goals.

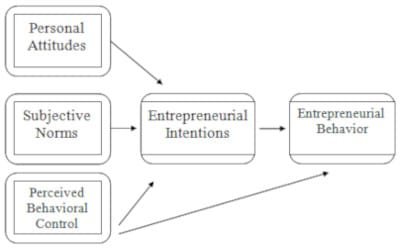

Behavioural Theories and Entrepreneurship

Management and behavioural experts have delved into entrepreneurship extensively, and there’s a whole body of work on the topic. Lazear paints a broad picture, defining an entrepreneur as someone who starts a new venture. But that definition lumps together someone opening a small local business with giants like Jeff Bezos or Steve Jobs. Sure, there’s some truth there, but it’s tricky to draw general conclusions about entrepreneurship because it comes in so many shapes and sizes. Entrepreneurship research tackles big questions like why some people dive into entrepreneurial ventures while others with similar talents and energy don’t, and why some spot entrepreneurial opportunities while others miss them.

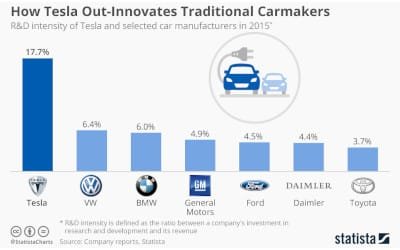

Tesla: Critical Evaluation of Corporate Social Responsibility and Global Innovation Management

Established in 2003, Tesla Motors, the US-headquartered manufacturer of electric vehicles, solar panels and solar roof tiles, has become globally famous for its pioneering, innovative and entrepreneurial efforts in the development of electric vehicles and renewable energy. The firm has grown phenomenally in the last two decades and is now one of the most valuable corporations in the world. Its CEO Elon Musk is currently one of the the wealthiest persons in the world

Competitive Advantage through the Learning Organisation

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theorists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

Communities of Practice in Knowledge Transfer

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theorists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

0 Comments