Ways to Manage Innovation in Business

Published in 2021

Introduction

This essay aims to examine the possibility of management of innovation and the ways in which innovation can, if at all, be managed successfully by businesses. It furthermore attempts to determine the ways in which knowledge of innovation management practices can help technology management in projects and organisations. The essay is sequentially structured with this introductory section being followed by a discussion on innovation management and thereafter by the ways in which knowledge of innovation management strategies and processes can help in enhancement of technology management.

Management of Innovation

Innovation has been defined as the process of translation of an idea or an invention into a product or a service that creates value for customers, who are ready to pay for them (Schumpeter, 1934). Joseph Schumpeter (1934) classified innovation into five types, i.e. (1) development of new products, (2) bringing about of process innovations, (3) developing fresh markets (4) developing fresh resources with regard to inputs and raw materials and (5) changes in industrial organisations.

It is important to differentiate invention from innovation, because whilst the former concerns the creation of a new product or service, innovation comes into play when it is successfully adapted for the use of people and creates value for both users and the sellers (Brady et al., 2012). Innovation has grown over the years into a critical driver of organisational success. Numerous widely acclaimed theorists and experts, like Joseph Schumpeter, Michael Porter and Peter Drucker have consistently stressed upon the need for organisations to engage in successful innovative activity for enhancement of competitive advantage and achievement of organisational success (Brady et al., 2012). It is also widely acknowledged that innovative activity has been able to dramatically alter business environments, as well as bring about various useful improvements in products and services (Afuah, 2003).

Apple’s introduction of iTunes for example dramatically altered the music business, whilst Amazon’s development of an online book store not only upended the book retailing sector but also enabled it to become the world’s largest book retailer (Dawson & Andriopoulos, 2009).

The tremendous potential of innovation, both in areas of customer empowerment and organisational advantage, notwithstanding, there many people continue to feel that achievement of successful innovation essentially occurs by chance and its successful harnessing is beyond the realm of organisational management (Tushman & Anderson, 2004). Advocates of such traditional approaches to innovation believe that the overwhelming majority of innovative activity, especially radical innovation, which has the power to transform business and society, is essentially an unpredictable process (Tidd & Bessant, 2009). With numerous people in various countries constantly working on various concepts, ideas and inventions, it is practically impossible to (1) predict the efforts that are likely to be successful or (2) harness and manage innovative activity successfully within specific organisation (Tidd & Bessant, 2009).

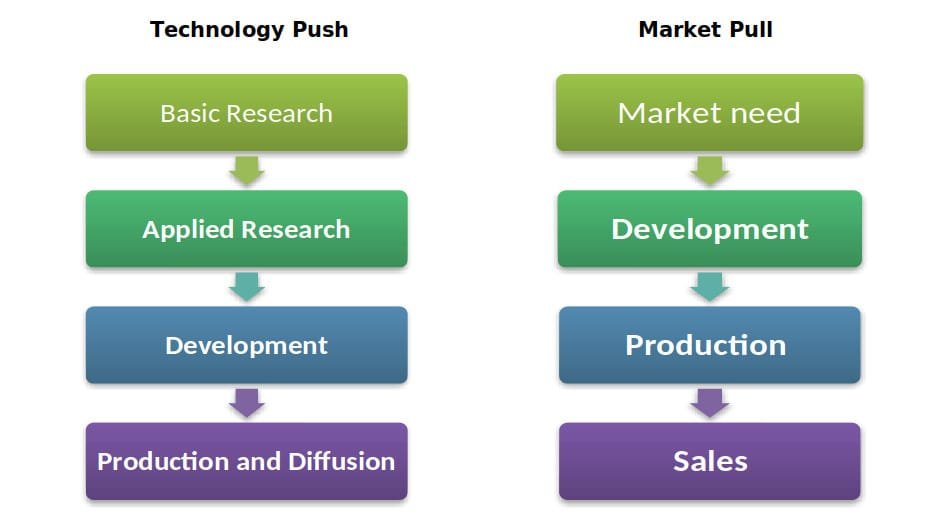

Contemporary innovation theory states that successful innovations occur in a linear nature, driven by push or pull processes (Preece et al., 2000). The linear innovation model has subsequently been modified into (1) the technology push model and (2) the market pull model (Tushman & Anderson, 2004). The following diagrams clearly depict and explain the ways in which innovation can be carried out by business organisations.

Diagram 1: Linear Innovation Models(Source: Godin, 2005, p 31: Smith, 2010, p 17)

The technology push model states that innovative activity commences in-house with clearly directed research and development efforts that lead to the creation of products and services and their subsequent market commercialisation (Mackinnon, 2007). The market pull model on the other hand states that organisations respond to market needs to develop products that are subsequently introduced into markets (Smith, 2010). It is important to note that the development of these two models moved innovation away from a chancy and unpredictable activity to a methodical process that could be followed by business organisations (Schlegelmilch et al., 2003).

Numerous management academics and practitioners, ranging from Peter Drucker and Michael porter to Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos have time and again stressed upon the need for organisations to perceive innovation as a critical business activity and take corporate decisions to incorporate innovation in organisational strategies (Knake & Segal, 2010).

The concept of strategic innovation, which has emerged from this reiterated need for methodical organisational innovative activity, concerns the fundamental re-conceptualisation of business models and reconfiguration of existing markets through the alteration of rules and changing the nature of competition (Von Hippel, 2007). It states that ontemporacry organisations should focus upon the development of appropriate organisational environments, frameworks, policies and processes for reconceptualising their business model and asking questions about their businesses, their customers and the ways in which they achieve value (Tushman & Anderson, 2004). They should thereafter focus upon the development of radically superior value in order to make competition irrelevant. Organisations must focus on creation of dramatic value improvements for customers (McLoughlin & Harris, 1997).

Schlegelmich et al., (2003) stated that business organisations could foster strategic innovation by focusing upon four important drivers, namely (1) culture, (2) processes, (3) people and (4) resources. There is wide agreement on the importance of the development of an innovative culture for the fostering of innovation (Von Hippel, 2005). It is important to identify the dominant mental models of an organisation, as evidenced in its culture, its approach to routines and unwritten behavioural rules and thereafter to create an organisational culture that focuses upon challenging orthodoxies, unleashing a sense of discovery and encouraging decision makers to view through different lenses in order to discover new perspectives (Schlegelmilch et al., 2003). Jeff Bezos, the founder and CEO of Amazon for example constantly works towards preserving an organisational culture that is basically questioning and dissatisfied with the status quo (Tidd & Bessant, 2009).

With regard to processes, strategic innovation theory states that organisations should not blindly accept prevalent business parameters and develop processes of creative exploration that combine conventional strategic thought with non traditional strategic options (Tidd & Bessant, 2009). The ideas and options that emerge from such processes should thereafter be analysed by senior managements to develop coherence and consistency (Tidd & Bessant, 2009). Hamel (2000) stated that organisational processes for selection of people play a strategic role in determining the ability of firms to engage in successful innovative activity. It is important for organisations to firstly employ people with tendencies for enquiry, inquisitiveness and problem solving and thereafter constantly provide them with opportunities for the development of new ideas (Preece et al., 2000).

Strong innovative organisations like Google, Apple and Amazon constantly encourage employees at all level to think out of the box and develop ideas and solutions that are relevant for the organisation (BBC News, 2013). Google, which is accepted to be one of the world’s most innovative organisations, provides its employees with the facility of using one day every week to pursue projects of their choice or liking (BBC News, 2013). The results of such research, in terms of generated ideas and concepts, are thereafter discussed in open forums and, if felt to be suitable, are supported by organisational resources for further development (Huang, 2013). Jeff Bezos of Amazon, on the other hand encourages the measurement of all new ideas and concepts developed within the organisation to assess their suitability for implementation (Huang, 2013).

Dawson and Andriopoulos (2009) have stated that innovation activity can also be helped by using an outside-in perspective with inputs from customers, suppliers, distributors, industry thinkers and consultants, all of whom can play active roles in driving innovation success. Google for example provides beta versions of its products under development in its Google Labs, inviting its customers and other outsiders to work with the organisation in product development (Iyer & Davenport, 2008). The organisation’s efforts to harness external minds in its innovative processes have proved to be immensely successful and resulted in numerous improvements and modifications to its beta products (Iyer & Davenport, 2008). Innovation experts like He & Wong, (2009) have also focused upon the need for organisations to provide adequate resources to drive innovative activities and processes. Major pharmaceutical organisations, which depend upon a pipeline of new products for achievement of competitive advantage and organisational success, support their research and development efforts with immense resources, which in turn are generated from the high prices of their new products (He & Wong, 2009). Many organisations do not however have access to such resources and have to formulate and develop alternate strategies for ensuring resource availability (Franke et al., 2006). Amazon for example stocks approximately 15% of its products in its own warehouses and coordinates with its business partners and external suppliers for the other 85% of its product inventory and sales, thereby ensuring availability of resources for supporting innovative activity (Johnson, 2010). Apple and Google have created huge populations of app developers who work on their own to develop apps for the Apple and Android operating systems, thereby multiplying the availability of their resources manifold (Morrison, 2009).

The preceding discussion and analysis clearly reveals that organisations can, if they wish, develop organisational abilities for achievement of successful innovative activity on a regular basis. Organisations like Apple, Google, 3M and Microsoft have developed tremendous internal organisational abilities and resources that enable them constantly to generate innovative products (Scott, 2013).

It also needs to be recognised that both Amazon and Google are run by young first generation entrepreneurs, who established their businesses a few years back and have been able to achieve tremendous growth on the basis of their innovative ability and their repeated success in innovation development (BBC News, 2013). It appears to be quite clear that innovation can be managed effectively with the application of appropriate strategies (Johansson & Loof, 2007).

Application of Innovation Theory in Technological Management in Projects and Organisations

The investigation carried out for the purpose of this study clearly reveals that whilst organisational innovation can be managed very successfully, it is not an easy process. Organisational managements must take great care in ensuring the development of appropriate organisational environments for the management of technical and other innovation (Howells, 2004). The organisational leaderships of contemporary firms desirous of achieving success in areas of technological management, both in organisational and project activity, have to focus upon some specific issues, namely organisational culture, organisational processes, the use of internal and external people and the application of appropriate resources (Howells, 2004). Each of these areas is taken up for detailed discussion below.

Organisational Culture

The culture of an organisation, which is essentially entrenched and developed over long time periods, plays an instrumental role in the shaping of organisational approaches and attitudes to various aspects of technological activity (Fang & Wang, 2006). Such cultures, which are evident externally, in the form of symbols, designations, hierarchies and other similar manifestations, and internally, in the form of organisational approaches towards detail, risk taking, information flows and openness to new ideas, play an exceedingly important role in the development of organisational technological and innovative abilities (Fang & Wang, 2006). Many organisations, which have excellent technical skills and infrastructure, may be restricted by conventional and orthodox cultural approaches and ideas and averse to the induction of new technological and scientific concepts and ideas (Putnam, 2003). It is thus exceedingly important for organisational managements to work towards the development of organisational cultures that encourage exploration and implementation of diverse new concepts, ideas and technological developments (Putnam, 2003).

The achievement of such cultural transformation can however take place only at the behest of senior organisational managements (Sims, 2002). The managements of businesses must, both in project and organisational activity, work towards the development of an organisational culture of enquiry and discussion (Sims, 2002). It is important to induct people with strong technological backgrounds and enquiring minds into the organisation and thereafter involve them in innovation activities and discussions (Putnam, 2003). Technological managers must be particularly asked to approach technical issues, difficulties and problems with an open mind, take inputs from internal and external sources and work towards generation of various alternatives in order to come up with viable solutions (Putnam, 2003).

Organisational Processes

It is important for innovation and technology oriented organisations to carefully construct organisational processes that empower organisational managers, officials and employees to approach technological issues with an enquiring and positive mind (Morrison et al., 2000). Successful innovation requires a well established process of creative exploration that essentially goes beyond existing business boundaries and synthesises unconventional options (Morrison et al., 2000). Various management academics and practitioners have voiced apprehensions that the development of such an exploratory process might work against existing analytic product development processes and result in adverse organisational outcomes (Morrison et al., 2000).

Hamel (2000) stated that organisational managements should, for the purpose of overcoming such challenges; focus on meshing exploratory technological thinking with scientific project development, rather than on attempt to replace one with the other. Amazon has for example achieved significant success in both radical and incremental innovation (Johnson, 2010). Its development officials constantly work towards enhancing existing processes, as is clearly evident from the ways in which the firm has been able to constantly achieve improvements in its customer buying experiences (Johnson, 2010). The firm at the same time encourages exploratory activity by members of its workforce (BBC News, 2013). Its recent proposal to deliver products to customers within 10 to 15 kilometres of its supply depots through small unmanned drones exemplifies its focus on radical innovation (BBC News, 2013).

Use of Organisational Employees and Partners

Research has revealed time and again that organisation known for excellence in areas of innovation and technology place great stress on the recruitment of high quality talent and the constant development of employees through various processes (Chawla & Renesch, 2006). Organisations like Apple, Google, Amazon and Swatch are known for their careful and detailed selection and recruitment processes, wherein individuals are selected, both for their technological knowledge and skills and for their enquiring, inquisitive and exploratory attitudes (Dawson & Andriopoulos, 2009). These organisations also take great care to provide employees with comfortable workplace environments, excellent training and skill development facilities and an atmosphere of urgency (Chawla & Renesch, 2006). Whilst employees are encouraged to experiment, think and act proactively, they are also kept under pressure to constantly generate ideas and thereafter get these ideas assessed by their peers (Chawla & Renesch, 2006).

Recent years have witnessed an ever increasing interest in the development of learning organisations, wherein efforts are made for development of five specific features, i.e. (a) systems thinking, (b) personal mastery, (c) mental models, (d) shared vision and (e) team learning (Gertler & Wolfe, 2002). Systems thinking assists employees in studying businesses as bounded organisations where performance is assessed in terms of the whole as well as elements (Gertler & Wolfe, 2002). Personal mastery relates to individual commitment to learning processes, leading to the development of an organisation with abilities for swift learning (Gertler & Wolfe, 2002). Mental models deal with deeply ingrained individual and organisational assumptions that require to be challenged, with confrontational attitudes towards new thoughts being replaced with open and welcoming approaches (Dawson & Andriopoulos, 2009). Shared vision relates to the building of an organisational identity that encourages cross learning, whereas team learning assists in the development of learning on a shared basis, thereby resulting in its swift absorption (Dawson & Andriopoulos, 2009).

Apart from these five attributes, learning organisations also focus on the conversion of tacit organisational knowledge into explicit knowledge through the use of various communities of practices, wherein employees are encouraged to engage with other people with whom they have common technological interests in both informal and formal ways in order to ensure sharing of individual tacit information and the development of a large organisational knowledge base (Burgelman et al., 2004).

Experts like Baldwin, et al., (2006) have stated that such dissemination of learning across an organisation and the development of eagerness for learning across levels and departments can help enormously in bringing about high levels of excellence in technological work, both in routine organisational operations and in the establishment of new projects. Employees at Google are deliberately provided with several types of common recreational facilities like Gyms, discussion forums and pleasant eating environments, where employees can get together beyond office hours and discuss with each other at length in pleasant environments (Google, 2011). Such interaction helps the organisation significantly in the dissemination of knowledge and in enhancement of technological and innovative ability (Google, 2011).

Constructive use of Organisational Resources

Academics like Chesbrough et al., (2011) agree that the level of achievement of technological and innovation excellence in organisations is significantly dependent upon the extent of support provided by senior managements to the development of new ideas and technologies through appropriate and adequate allocation of resources. Research on innovation reveals that several brilliant and innovative ideas have failed and not been taken up for adaptation and introduction because of organisational apathy and disinclination to support such ideas with appropriate resources (Desouza et al., 2008). It has been found that organisational managements often fail to support technological suggestions and innovative ideas on account of reasons like their lack of knowledge about the subject, apprehensions about wastage of money and organisational power systems and conflicts (Desouza et al., 2008). There is widespread agreement that whilst it is important for organisations to conserve their finances and use them productively, the failure to support potentially promising ideas and processes could result in significantly adverse organisational outcomes (Banks, 2013). The research and development team at Kodak Palo Alto for instance developed the personal computer and various associated applications much before Steve Jobs unveiled his Mackintosh (Chesbrough et al., 2011). These innovations were however not encouraged by the conservative senior management of the company and resulted in the loss of a tremendous business opportunity (Baldwin et al., 2006).

It is thus recommended that organisational managements should develop specific processes for assessing the worth and viability of new ideas and concepts through fair, unbiased and technically competent organisational processes before taking decisions on resource allocation (Afuah, 2003). Technologically successful organisations like Apple, Microsoft and Google have developed specific processes for idea generation and idea assessment in order to ensure appropriate allocation of resources (Johansson & Loof, 2007). New ideas are by and large judged by peer groups and their recommendations are considered seriously by senior management for the allocation of resources. Such carefully developed processes of resource allocation help significantly in the nurturing and furtherance of technological developments (Drucker, 2006)

Conclusion

The investigations carried out for the purpose of this study clearly revealed that organisations can foster the growth of innovative environments and achieve success in the development of innovative and technologically superior projects through the careful formulation and application of organisational strategies in areas of development of people and processes as well as through the support of good ideas and processes with appropriate resources. It has been practically seen that the actual application of carefully formulated strategies in these areas can result in significant success in the development of technologies and innovative products.

References

Afuah, A., 2003, Innovation Management: Strategies, Implementation, and Profits, 2nd edition, Oxford: OUP USA.

Baldwin, C. Y., Hienerth, C., & Von Hippel, E., 2006, “How user innovations become commercial products: a theoretical investigation and case study”, Research Policy, Vol. 35, Iss (9): pp. 1291–1313.

Banks, M., 2013, “Securing the technology that underpins innovation”, Available at: http://horizon-magazine.eu/article/securing-technology-underpins-innovation_en.html (accessed April 16, 2014).

BBC News, 2013, “Amazon testing drones for deliveries”, Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-25180906 (accessed April 16, 2014).

Brady, T., Davies, A., & Nightingale, P., 2012, “Dealing with uncertainty in complex projects: revisiting Klein and Meckling”, International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, Vol. 5, No (4): pp.718 – 736.

Burgelman, R.A., Christensen, M.C., & Wheelwright, C.S., 2004, Strategic management of technology and innovation, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Chawla, S., & Renesch, J., 2006, Learning Organizations: Developing Cultures for Tomorrow’s Workplace, 1st edition, UK: Productivity Press.

Chesbrough, KH., Vanhaverbeke, W., & West, J., 2011, Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dahlander, L., & Gann, D.M., 2010, “How open is Innovation?”, Research Policy, Vol. 39, No (6): pp. 699-709.

Dawson, P., & Andriopoulos, C., 2009, Managing Change, Creativity and Innovation,

London: Sage Publications.

Desouza, K. C., Awazu, Y., Jha, S., Dombrowski, C., Papagari, S., Baloh, P., 2008, “Customer-driven Innovation”, Research Technology Management, Vol. 51, Iss (3): pp. 35.

Drucker, F. P., 2006, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Reprint Edition, USA: HarperBusiness.

Fang, S., & Wang, J., 2006, “Effects of Organizational Culture and Learning on Manufacturing Strategy Selection: an Empirical Study”, International Journal of Management, Vol. 23, No. (3): pp. 504- 511.

Franke, N., Von Hippel, E., & Schreier, M., 2006, “Finding commercially attractive user innovations: a test of lead-user theory”, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 23, pp. 301–315.

Gertler, M. S. & Wolfe, D. A., 2002, Innovation and Social Learning : Institutional Adaptation in an Era of Technological Change, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Godin, B., 2005, “The Linear Model of Innovation: The Historical Construction of an Analytical Framework“, Available at: http://www.csiic.ca/PDF/Godin_30.pdf (accessed April 16, 2014).

Google, 2011, “Diversity in our culture and workplace”, Available at: www.google.com/diversity/culture.html (accessed April 16, 2014).

Hamel, G. (2000) Leading the Revolution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

He, Z., & Wong, P., 2009, “Knowledge Interaction with Manufacturing Clients and Innovation of Knowledge-intensive Business Services Firms”, Innovation : Management, Policy & Practice, Vol. 11, Iss (3): pp. 264.

Howells, J., 2004, The Management of Innovation and Technology, London: Sage.

Huang, T.G., 2013, How Amazon Innovates: Lessons in Strategy for Microsoft and Others, Available at: http://www.xconomy.com/seattle/2010/02/25/how-amazon-innovates-lessons-in-strategy-for-microsoft-and-others/ (accessed April 16, 2014).

Iyer, B., & Davenport, H, T., 2008, “Reverse engineering Google’s innovation machine”, Harvard Business Review Article, Available at: hbr.org/…/reverse-engineering-google…innovation-machine/…/R0804C-PDF-ENG (accessed April 16, 2014).

Johansson, B., & Loof, H., 2007, Innovation Activities explained by firm attributes and Location, Economics of Innovation and new Technology, Vol. 16, no. 8.

Johnson, W.M., 2010, “Amazon’s Smart Innovation Strategy”, Available at: http://www.businessweek.com/innovate/content/apr2010/id20100412_520351.htm (accessed April 16, 2014).

Knake, R., & Segal, A., 2010, “Google’s lesson: Innovation Has to Be Accompanied by Reliability”, Available at: yaleglobal.yale.edu/…/googles-lesson-innovation-accompanied-reliability (accessed April 16, 2014).

Mackinnon, K. A. L., 2007, “Google on Innovation”, Available at: www.think-differently.org/2007/08/google-on-innovation/ (accessed April 16, 2014).

McLoughlin, I., & Harris, M., 1997, Innovation, Organisational Change and Technology, London: International Thompson Business Press.

Morrison, C., 2009, “How to Innovate like Apple”, www.bnet.com, Available at: www.bnet.com/article/how-to-innovate-like-apple/330240 (accessed April 16, 2014).

Preece, D., Mcloughlin, I., & Dawson, P., 2000, Technology, Organizations and Innovation: Critical Perspectives on Business and Management, London: Routledge.

Putnam, L. L., 2003, “Organizational Culture: Mapping the Terrain”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 48, Iss (1): pp. 131-145.

Scott, A., 2013, “The Three Most Innovative Companies of 2013”, Available at: http://blogs.hbr.org/2013/12/the-three-most-innovative-companies-of-2013/ (accessed April 16, 2014).

Schlegelmilch, B.B., Diamantopoulos, A., & Kreuz, P., 2003, “Strategic innovation: the construct, its drivers and its strategic outcomes”, Journal of Strategic Marketing, Vol. 11, pp. 117-132.

Schumpeter, J. A., 1934, The theory of Economic Development, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Sims, R. R., 2002, Managing Organizational Behavior. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Smith, D., 2010, Exploring Innovation, 2nd edition, NY: McGraw Hill.

Tidd, J., & Bessant, J., 2009, Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change, Chichester: Wiley.

Tushman, L.M., & Anderson, P., 2004, Managing Strategic Innovation and Change: A Collection of Readings, USA: Oxford University Press.

Von Hippel, E., 2007, “Horizontal innovation networks by and for users”, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 16, Iss (2): pp-1-23.

Von Hippel, E., 2005, Democratising Innovation, Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

More From This Category

Innovation & Change are Central to Value Creation

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theoInnovation, as a concept, has been examined and developed over time, which, in turn, has resulted in the creation of several definitions. Innovation entails the conversion of an idea into a solution that results in addition to value from the perspectives of customers. Customers are unlikely to change their buying behaviour if an innovative product does not result in value addition for them. Innovation involves the application of useful and novel ideas; creativity comprises the seed of innovation but is likely to remain in the realm of idea generation until and unless it is applied and scaled suitably).

Organisational change constitutes the process of alteration of organisational strategies, processes, procedures, technologies, and culture.rists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

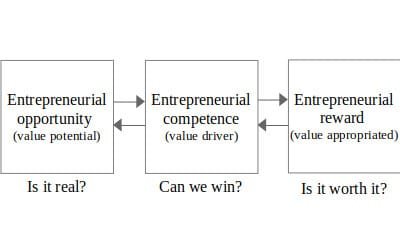

Theories of Entrepreneurial Opportunity

The study of entrepreneurship isn’t just about admiring successful entrepreneurs from afar. It’s about digging deep into why they do what they do, when they do it, and how it all plays out in the end. It’s like peeling back the layers of an onion to uncover the juicy bits inside.

And to tackle these burning questions, we’ve got two heavyweights in the ring: the Discovery Theory and the Creation Theory. These bad boys are all about figuring out why humans do what they do and how it helps them achieve their goals.

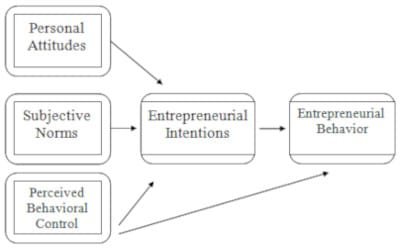

Behavioural Theories and Entrepreneurship

Management and behavioural experts have delved into entrepreneurship extensively, and there’s a whole body of work on the topic. Lazear paints a broad picture, defining an entrepreneur as someone who starts a new venture. But that definition lumps together someone opening a small local business with giants like Jeff Bezos or Steve Jobs. Sure, there’s some truth there, but it’s tricky to draw general conclusions about entrepreneurship because it comes in so many shapes and sizes. Entrepreneurship research tackles big questions like why some people dive into entrepreneurial ventures while others with similar talents and energy don’t, and why some spot entrepreneurial opportunities while others miss them.

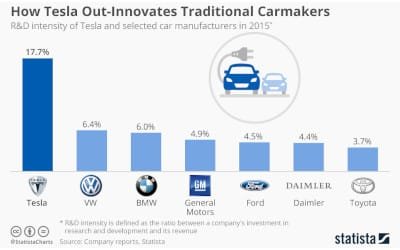

Tesla: Critical Evaluation of Corporate Social Responsibility and Global Innovation Management

Established in 2003, Tesla Motors, the US-headquartered manufacturer of electric vehicles, solar panels and solar roof tiles, has become globally famous for its pioneering, innovative and entrepreneurial efforts in the development of electric vehicles and renewable energy. The firm has grown phenomenally in the last two decades and is now one of the most valuable corporations in the world. Its CEO Elon Musk is currently one of the the wealthiest persons in the world

Competitive Advantage through the Learning Organisation

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theorists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

Communities of Practice in Knowledge Transfer

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theorists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

0 Comments