Importance of Financial Stability: Lessons from the Financial Crisis

Published in 2016

Introduction

The international financial crisis, which started in the USA with the crash in the housing market and the emergence of the sub-prime predicament, did not take more than a year to spread across the world!!

The sub-prime crisis occurred largely because of the inappropriate and risky utilisation of financial instruments like securitisation, a process banks used to group their loans, convert them into saleable assets, and thereby transfer their loans, risky or otherwise, to others (Barrel & Davis, 2008). Whilst banks make very good money from interest bearing loans, such loans tie up bank capital for years on end (Barrel & Davis, 2008). Securitisation, seen as the most important financial innovation of current times, allowed banks to enlarge their cash flows exponentially and offload their risk (Barrel & Davis, 2008). The profits perceived as possible through use of securitisation led banks to take on enormous additional risks. They engaged in indiscriminate lending to sub-prime borrowers, borrowed extensively, and entered into various forms of investment banking, with buying, selling, and trading risk (Barrel & Davis, 2008).

The bursting of the housing bubble exposed this huge can of worms in the American financial system; it led to erosion of confidence and widespread banking collapses, not just in investment banks with little deposits, but also in large banks with substantial capital reserves (Engelen, 2008). Financial experts, most of them in hindsight, argue that the current financial downturn and the accompanying economic recession have occurred primarily because of unsupervised financial innovations and lax regulatory action (Rude, 2008).

An extended period of economic growth characterised by low default rates led to increasing deregulation and the growth of numerous unmonitored financial innovations (Rude, 2008). Whilst financial organisations created such innovations to increase their market share and profitability, it was the malfunctioning of the regulatory system to apprehend and control the inherent volatility of free market mechanisms that led to the financial crisis (Rude, 2008). Phenomena like excessive sub-prime lending and speculation by otherwise conservative financial managers were merely symptoms of the larger mechanisms behind them (Rude, 2008).

This report takes up the reasons behind the regulatory failure in managing systemic risk and maintaining financial stability, with especial reference to the understanding of the implications of changes in the banking and financial sector by regulatory authorities. The analysis is followed by appropriate recommendations on what regulators need to imbibe from the current financial crisis.

Recent Changes in Banking and Financial Markets

Recent decades have experienced an unprecedented and sharp increase in the working of the financial sector, especially so in the advanced nations (Honohan, 2008). The entry of hordes of educated number crunchers from top level management institutes into the sector has resulted in continuous innovation and a slew of new products, carrying greater returns in an era of significantly low financial costs (Honohan, 2008).

The complex nature of many of these new instruments, as well as of the interrelated international markets that developed side by side with them, was such that it became increasingly hard for banks, investors and regulators to fully comprehend their various dimensions, especially with regard to the involved risks (Honohan, 2008.

The existing regulatory systems have not kept pace with the innovations and alterations in the banking and financial system in the recent past (Honohan, 2008). They have in fact made it possible for banks and other business firms to conceal their operations from the eyes of the regulators through a number of methods like the formation of off-balance sheet entities, use of offshore financial centres and utilisation of intricate derivative instruments (Honohan, 2008). The growth of securitisation, the use of credit derivatives and the progressive movement of the financial system from bank-centric to market-c, P 16+).

Whilst little has been done by regulators to control excessive leverage in banks and financial institutions, (or their taking on of additional risk), through modification of regulatory procedures, such organisations have on the other hand been supported by central banks and regulators to formulate and implement their own internal risk assessment and control procedures (Honohan, 2008).

The mistaken belief that markets tend to price risks properly, as also the conviction that aggregated market risks can be managed and controlled, have been causal in the development of such phenomena (Rude, 2008). The risk models adopted by banks turned out to be inherently flawed and based upon an inadequate understanding of financial principles (Rude, 2008). It was mistakenly assumed that risks could be widely distributed through methods like securitisation (Rude, 2008, P1+). The risks that crept into the system, on account of greatly enhanced leverage, were thus underestimated (Rude, 2008). The remuneration policies followed by banks, which tended to reward managers with fat bonuses for short term gains, were instrumental in the disguising of extremely risky financial positions by the blatant use of confusing jargon and purposeful posturing (Pfaff, 2008). Market discipline, which was considered to be a constraining factor, proved to be inadequate in the face of collective disregard for the principles of fiscal prudence and conservatism (Pfaff, 2008). Serious deficiencies crept into the corporate governance of major banking organizations (Rude, 2008). The boards and senior management of major banks failed to comprehend or investigate the risks and risk management processes assumed by their organisations (Rude, 2008).

Recent years have seen a much greater role being played by credit rating agencies, whose findings have been considered to be gospel and of greater worth than internal assessments, due diligence and rigorous internal analysis (Barrell & Davis, 2008). The failure of credit rating agencies to grasp the implications of off-balance sheet accounting and special purpose vehicles was instrumental in allaying investor concern about the safety of their investments (Barrell & Davis, 2008).

The central banks and regulators of western countries grossly undervalued the risks that were building up in the financial system (Caprio & College, 2009). They were also unable to appreciate the true nature of systemic risks or the wider repercussions of actions outside regulatory perimeters, especially with regard to (a) the construction by banks of excessive exposure to special purpose or off-balance sheet vehicles, and (b) the opacity that characterised them (Caprio & College, 2009).

Importance of Financial Stability

The unprecedented turmoil brought about by the financial crisis of 2008 underlined the need for financial stability and illuminated the many challenges that must be overcome for achieving it (Marks, 2009). The stability of local and international financial systems refers to the capacity of such systems to fulfil their objectives under varied circumstances (Marks, 2009). The financial systems provide avenues and routes for savings to transform into investments, for transfer of money, and for settlement of financial claims (Marks, 2009). Such systems ensure the allocation of risks to those agreeable and able to bear them (Marks, 2009).

Stability in financial systems demands the confidence of households, investors and firms (Marks, 2009). The importance and stability of financial systems to regulators can easily be assessed by the consequences of disruption in such systems (Marks, 2009). It is now clearly perceptible that the majority of investors (sophisticated or otherwise) had inadequate knowledge or understanding of their investments (Marks, 2009). Their frantic and greedy quest for greater yields led them to assume that others knew their jobs and that risk had been provided for appropriately (Marks, 2009).

In all countries, banks operate as the chief intermediary between people who wish to borrow funds and those who wish to deposit their money in savings (Singer, 2009). Such savings combine together and become available to those who need to take loans for their particular needs (Singer, 2009). Financial systems connect hundreds of thousands of savers across countries and continents with millions of borrowers through enormous numbers of individual transactions (Singer, 2009). Such inordinately complex but effective systems include banks and financial institutions and develop over time (Singer, 2009). Based upon the trust of individual savers such systems are essential for the financial and economic health of local and national societies (Singer, 2009).

Regulators are well aware that the collapse of such systems could lead to unimaginable and profound economic implications for individuals and societies (Pitti, 2009). The ongoing financial crisis is being widely perceived as a regulatory failure and has led to numerous demands and suggestions for increased governmental and institutional regulation (Pitti, 2009).

Complexity of Systemic Risks in Financial Sector

Systemic risks represent the hazards that can arise from one or more triggering episodes, like, for example, the adverse impact of the collapse of an individual business on other firms and on the larger economy (Rude, 2008). The most significant risk to the financial system in the ongoing financial crisis arose from counter party risks i.e. the chance that firms may not succeed in meeting their obligations in financial contracts (Rude, 2008). Such risks arise because of the presence of asymmetric information, to elaborate, the phenomenon of individuals and businesses knowing much more about their own financial affairs than other parties (Rude, 2008).

Systemic risks are high in the case of financial banks dealing in complicated financial contracts (Bullard & Others, 2009). Whilst banks participating in such contracts can protect their self-interest by insisting on collateral, actual market conditions are so complex that the nature of risks are often difficult to ascertain (Bullard & Others, 2009).

Again, although systemic risks may not be uniquely specific to banks or financial institutions, it is also true that the failure of a non-financial business will rarely pose a significant threat to competitors, or to the larger economy (Rude, 2008). The situation is starkly different in the case of financial firms, where major banks and investment institutions trade with each other via a number of channels like inter-bank markets, over the counter derivatives, and systems for wholesale payment as well as settlement (Rude, 2008). Settlement risks (the chance that one of the parties to a financial contract may default even after delivery by the other party takes place) continues to pose a major concern for large organisations that routinely expose themselves to billions of dollars in such transactions (Rude, 2008).

Instantaneous execution of financial transactions and complex bank and security firm structures make it exceptionally difficult to watch the action of counter parties or of counter parties of counterparties (Rude, 2008). The quick crumpling of an apparently strong banking organisation could very easily render its counterparties vulnerable to substantial losses. Even third parties can be adversely affected in such situations (Rude, 2008).

The financial sector is especially prone to systemic risk because of its inordinately high leverage (Bullard & Others, 2009). Banks are geared much more than non-financial businesses (Bullard & Others, 2009). The high proportion of debt in their long term capital structure not only leads to very high rates of return in shareholder funds in good times, but also attracts significant risks of failing during economic downturns (Bullard & Others, 2009). The major reasons for the collapse of investment banks like Fannie May and Freddie Mac were the lesser amount of equity funds in their capital structures vis-à-vis their inordinately high debts (Bullard & Others, 2009).

The financial sector is also more vulnerable to systemic risk than other business areas because of the practice of financial businesses to fund illiquid assets that are primarily long term in nature with debt that is short term (Bullard & Others, 2009). Many financial intermediaries fund long term investments with short term borrowings (Bullard & Others, 2009). The excessive leverage of such institutions along with mismatches in the maturities of their liabilities and assets makes them intensely vulnerable to interest rate or liquidity disturbances (Bullard & Others, 2009).

Role of Regulators in Management of Systemic Risk

Researchers and experts appear to be unanimous in their view of financial market regulation before the financial crisis being pro-cyclical, contradictory, out-of-date and deficient, and lacking in its need to address the needs of banks with regard to short-term liabilities and liquidity needs; such regulation is based on the faulty premise that the assessment of systemic risks by markets can be trusted (Engelen, 2008).

The banking regulations circulated by the Basel Committee on Banking Regulation prior to 2008, with its stress on least capital requirements, light control and supervision, and market regulation, were innately pro-cyclical; these regulations prompted investors to increase risky investments during business upswings and reduce investments during downturns, which increased rather than reduced the volatility of financial markets and the fundamental real economy (Engelen, 2008).

Existing regulations have not been able to keep up with alterations in the banking and financial structure, encouraging regulatory arbitrage and allowing banks and other similar institutions to conceal their behaviour from regulators through special purpose vehicles (Engelen, 2008).

Regulators were also unable to address the liability side problems that arose from the inability of banks and financial institutions to roll over short-term debt (Engelen, 2008).

Conclusions and Recommendations

With it now being obvious that the financial crisis was allowed to occur because of the lack of understanding of regulators regarding the multifarious implications of the innovations that had freely been allowed into the operating space of banks and financial institutions, the Obama administration unveiled reform proposals to achieve five key objectives:

“(i) Increasing oversight of systemic risk and financial regulation, (ii) strengthening regulation of core markets and market infrastructure, (iii) strengthening consumer protection, (iv) giving the government tools to effectively manage financial crises, and (v) improving international regulatory standards and cooperation.” (Obama Administration, 2009, p1)

The securitisation proposals, for example, aimed to alter incentive structures for market members, reduce opacity to help in investor due diligence, reinforce the role of credit rating organisations, and lessen dependence on credit ratings (Singer, 2009).

Whilst the new proposals were elaborate and were accompanied by specified increases in capital adequacy requirements, care must be taken to ensure that regulations are complete and that they take account of all institutions, actions, markets and instruments, specifically including off-balance sheet items, off shore centres, tax havens and hedge funds.

The absence of completeness in regulation will lead to the development of shadow finance systems, making it difficult to prevent excessive leveraging and regulatory arbitrage, both of which were causal to the current crisis.

All types of banking and financial actions will need to be checked, including underlying and derivative securities, as well as securities traded through OTC and exchange routes. Organisations operating in areas of trading, insurance, pensions and mutual funds need to be reviewed.

“Very concisely the market domain must be that of the regulators, for the purpose of regulation” (Singer, 2009, p25).

References

Alan, F., & Douglas, G., (2006). Systemic Risk and Regulation. Bank of Portugal Conference on “Financial Fragility and Bank Regulation”.

Marks, R. (2009). “Anatomy of a Credit Crisis”. Australian Journal of Management. 34 (1): 1-10.

Barrell, Ray, and E. Philip Davis. 2008. The Evolution of the Financial Crisis of 2007-8. National Institute Economic Review, no. 206: 5+

Buckley, William F. 2008. Regulation Time?. National Review, January 28, 59

Bullard, James, Christopher J. Neely, and David C. Wheelock. 2009. Systemic Risk and the Financial Crisis: A Primer. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, September/October 2009, 91(5, Part 1), 403+

Caprio, Gerard and W. College. 2009. Financial Regulation in a Changing World: Lessons from the Recent Crisis. Paper prepared for the VII Colloquium on “Financial Collapse: How are the Biggest Nations and Organizations Managing the Crisis?”,

Chorafas, Dimitris N. 2000. New Regulation of the Financial Industry. Basingstoke, England: Macmillan

Engelen, Klaus C. 2008. The Post-Subprime Regulation Scramble: The Regulators and Market Players Pick Up the Pieces. The International Economy, Wntr, 62+

Honohan, Patrick. 2008. Risk Management and the Costs of the Banking Crisis. National Institute Economic Review, no. 206: 15+

Leinberger, Christopher B. 2008. The Next Slum? the Subprime Crisis Is Just the Tip of the Iceberg. Fundamental Changes in American Life May Turn Today’s McMansions into Tomorrow’s Tenements. The Atlantic Monthly, March, 70+

Obama Administration Publishes Proposed Regulatory Overhaul. 2009. Alston and Bird Financial Crisis Blog, http://www.alston.com/financialmarketscrisisblog/blog.aspx?entry=2215, 28 November, 2009

O’Sullivan, Orla. 2008. Online Lending Circles Hit Circuit Breaker: What Will Possible SEC Regulation Mean for P-to-P Lenders, a Rising Bank Competitor-And Potential Partner?. ABA Banking Journal 100, no. 5: 7+

Pfaff, William. 2008. Shell Game: The Subprime Mortgage Swindle. Commonweal, April 11, 6

Pitti, Don. 2009. New Regulation Will Drive Trends in the Financial Services Industry-Again. Review of Business 29, no. 2: 4+

Rating the Toxic Fallout from Subprime Crisis. 2007. The Evening Standard (London, England), July 24, 27

Rude, Christopher. 2008. The Global Financial Crisis: What Needs To Be Done? FES Briefing Paper, 1+

Scott, Hal S., ed. 2005. Capital Adequacy beyond Basel: Banking, Securities, and Insurance. New York: Oxford University Press

Singer, David Andrew. 2009. The Subprime Accountability Deficit and the Obstacles of International Standards Setting. Global Governance 15, no. 1: 23+

Squires, Gregory D., ed. 2004. Why the Poor Pay More: How to Stop Predatory Lending. Westport, CT: Praeger

More From This Category

Innovation & Change are Central to Value Creation

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theoInnovation, as a concept, has been examined and developed over time, which, in turn, has resulted in the creation of several definitions. Innovation entails the conversion of an idea into a solution that results in addition to value from the perspectives of customers. Customers are unlikely to change their buying behaviour if an innovative product does not result in value addition for them. Innovation involves the application of useful and novel ideas; creativity comprises the seed of innovation but is likely to remain in the realm of idea generation until and unless it is applied and scaled suitably).

Organisational change constitutes the process of alteration of organisational strategies, processes, procedures, technologies, and culture.rists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

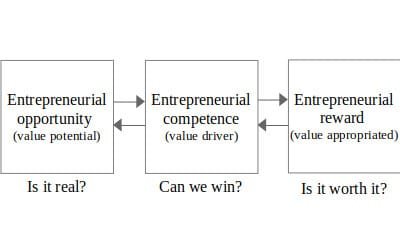

Theories of Entrepreneurial Opportunity

The study of entrepreneurship isn’t just about admiring successful entrepreneurs from afar. It’s about digging deep into why they do what they do, when they do it, and how it all plays out in the end. It’s like peeling back the layers of an onion to uncover the juicy bits inside.

And to tackle these burning questions, we’ve got two heavyweights in the ring: the Discovery Theory and the Creation Theory. These bad boys are all about figuring out why humans do what they do and how it helps them achieve their goals.

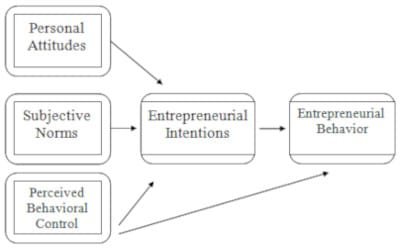

Behavioural Theories and Entrepreneurship

Management and behavioural experts have delved into entrepreneurship extensively, and there’s a whole body of work on the topic. Lazear paints a broad picture, defining an entrepreneur as someone who starts a new venture. But that definition lumps together someone opening a small local business with giants like Jeff Bezos or Steve Jobs. Sure, there’s some truth there, but it’s tricky to draw general conclusions about entrepreneurship because it comes in so many shapes and sizes. Entrepreneurship research tackles big questions like why some people dive into entrepreneurial ventures while others with similar talents and energy don’t, and why some spot entrepreneurial opportunities while others miss them.

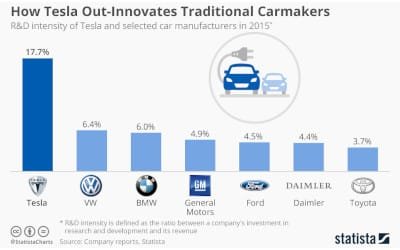

Tesla: Critical Evaluation of Corporate Social Responsibility and Global Innovation Management

Established in 2003, Tesla Motors, the US-headquartered manufacturer of electric vehicles, solar panels and solar roof tiles, has become globally famous for its pioneering, innovative and entrepreneurial efforts in the development of electric vehicles and renewable energy. The firm has grown phenomenally in the last two decades and is now one of the most valuable corporations in the world. Its CEO Elon Musk is currently one of the the wealthiest persons in the world

Competitive Advantage through the Learning Organisation

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theorists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

Communities of Practice in Knowledge Transfer

The achievement and effective use of knowledge is widely accepted by contemporary managements, theorists and researchers to be the chief source of competitive advantage of modern day business organisations.

0 Comments