Cross-Cultural Communication Challenges: Dealing with China

Introduction

This report, prepared at the request of the Senior International Business Manager of Alliance Boots GmbH, aims to provide an investigative and analytical assessment of the organisation’s proposed plan for the establishment of a joint venture for the development of alternative medicines in China (Alliance Boots, 2013).

Alliance Boots, (AB), which has been operating in the area of pharmaceuticals and beauty products for more than 160 years, already has an equal shareholding joint venture with the Chinese firm Guangzhou Pharmaceutical Holding Limited, in the shape of Guangzhou Pharmaceutical Corporation (GPC). The joint venture, which was established in 2007, is engaged in the wholesaling of medicines and medical equipment (Alliance Boots, 2013).

The new venture will, however, deal with the production and sale of significantly different products, namely alternative medicines, which contain animal body parts and are integral to traditional Chinese culture. With the new project entailing not only the need to work in close partnership and collaboration with a local party but also the establishment and operations of a production and manufacturing facility, its effectiveness and success will to a large extent depend upon the successful management of diverse cross-cultural issues and differences between the organisation’s UK operations and the Chinese venture.

There is wide acknowledgement of the numerous sharp, as well as subtle, differences between the cultures of different countries (Brislin, 2008). With national cultures playing an immensely important role in the shaping and influencing of the thinking processes, attitudes, approaches and behaviours of the inhabitants of individual countries, differences in various dimensions and manifestations of national cultures are perceived to be important drivers of divergences in the workplace behaviours of people from different cultural and national backgrounds (Brislin, 2008).

Geertz Hofstede, Fons Trompenaars, and several other behavioural experts have conducted extensive research on the cultures of different nations and the impact of cultural dissimilarities on workplace behaviour and the conduct of global business operations. Browaeys & Price, (2008), have in particular, studied and analysed the impact and role of diverse dimensions of national culture in the management of global business.

The presence of extensive cultural differences in organisations makes the management of multicultural organisations an extremely challenging and complex task (Ferraro, 2002). With AB’s proposed joint venture for production and sale of alternative medicines in China involving the management of joint venture partners and organisational employees of significantly different cultural backgrounds, its success will to a large extent, depend upon the abilities of the firm’s managers to handle diverse cross-cultural issues, as also to coordinate and communicate effectively with Chinese partners and employees (Ferraro, 2002).

The establishment of a venture for the production of alternative medicines in China is also bound to result in the development of several relevant ethical and commercial challenges that will need to be clearly identified, dealt with, and overcome in the most appropriate manner. This report aims to analyse and critically assess the various cross-cultural, ethical, and commercial challenges that can stem from the establishment of the Chinese joint venture and provide appropriate recommendations for the management of diverse cross-cultural challenges.

Cross-Cultural Management

Cross-cultural management basically concerns the strategic deployment of specific management approaches for overcoming the workplace challenges that can arise from the differences in the national cultures of organisational executives, employees and diverse other stakeholders (Gannon, 2004).

Geert Hofstede, internationally acknowledged for his pioneering and groundbreaking work on (a) the unique features of national cultures, (b) the differences between the cultural traits of peoples from different nations, and (c) the impact of such cultural divergences on individual and joint workplace behaviour, put forward five important cultural dimensions, e.g. individualism v collectivism, masculinity v femininity, uncertainty avoidance, power distance and long v short term orientation (Hofstede, 2001). Whilst his initial research resulted in the elaboration of the first four dimensions in the early 1970s, the fifth cultural dimension, i.e. term orientation was added later, after extensive study of oriental cultures, in the early 1990s (Hofstede, 2001).

Hofstede (2001) stated that the people of countries with high degrees of individualism were likely to be focused upon the interests and welfare of themselves and their immediate families to the exclusion of everybody else. The members of collectivist societies, on the other hand, have deep allegiance to their communities, which include their extended families and other in-groups, such allegiance being rewarded with the support and protection of the larger community for such individuals and their families (Hofstede, 2001).

Masculine societies are distinguished by higher degrees of assertive behaviour, aggression and business competition, whilst the individuals of less masculine, or inversely more feminine societies, are known for their understanding of the arts, their compassionate and caring nature, and their preference for overall quality of life, rather than for aggressive competition in the market place (Hofstede, 1991). A high power distance index implies the acceptance by members of society of inequalities in social power structures and of differences in power, income and authority between different organisational and social segments (Hofstede, 1991). Societies with high power distance indices are associated with hierarchical organisational structures, command and control management and the dependence of lower-level employees upon their seniors for decision-making purposes and allocation of responsibilities (Hofstede, 1991). Societies with lower power distance indices are, on the other hand, characterised by far greater organisational equality and greater respect for junior employees by peers and senior executives (Hofstede, 1991).

The uncertainty avoidance index concerns the tolerance of people for uncertainty and ambiguity in their lives (Hofstede, 2001). Societies with low uncertainty avoidance indices are more open to various types of ambiguities and are comfortable with new ideas and thoughts. Such societies encourage innovation, as well as social and organisational change (Hofstede, 2001). Societies with high uncertainty avoidance indices are, on the other hand, characterised by the preference for customs, traditions, rules and regulations and the mistrust of new ideas and thoughts (Hofstede, 2001). Such societies are comfortable with organisational hierarchies and the need to carry out work in traditional ways (Hofstede, 2001).

Long term orientation represents social preferences for issues like education, perseverance and savings, which result in long term benefits, whilst short term orientation stands for obsession with issues like immediate achievement, immediate satisfaction and short term rewards (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). Hofstede stated that whilst the people of all societies had these five cultural traits, their level differs significantly from society to society and results in very significant cultural differences (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005).

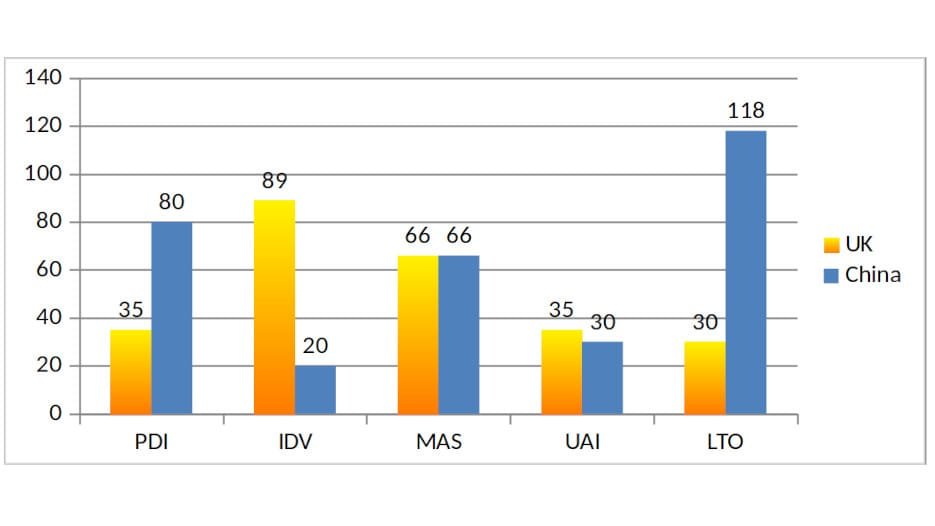

Hofstede’s ranking of the cultural dimensions of the UK and China are provided in the following charts and tables.

Country | PDI | IDV | MAS | UAI | LTO |

UK | 35 | 89 | 66 | 35 | 25 |

China | 80 | 20 | 66 | 30 | 118 |

(Source: ITim International, 2012)

(Source: ITim International, 2012)

The above charts and tables reveal that whilst close similarities exist between UK and Chinese cultures in areas of masculinity and uncertainty avoidance, strong dissimilarities exist in power distance, individuality and long term orientation. The high masculinity score indicates that the Chinese people are driven by competition and success and want to be winners. They are also very comfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty.

The high power distance index for China reveals that the Chinese are comfortable with, and accepting of, inequalities between people. Relationships between superiors and subordinates are likely to be polarised and juniors are likely to have little defence against the abuse and misuse of power by superiors. Most employees are thus unlikely to have aspirations beyond their social and workplace ranks.

The low ranking for individualism suggests that the Chinese culture is likely to be highly collectivist, where individual people are likely to act for the benefit of their groups, rather than their own selves. Such collectivism can certainly influence workplace decisions like hiring or promotions, with people of in-groups getting preference over others. It is important to keep in mind that whilst collaboration and cooperation between colleagues in in-groups in such societies are likely to be cordial and collaborative, they can be cold and even hostile between people belonging to different groups.

China’s extremely high score of 118 in term orientation makes it a highly long term oriented society. It is normal for people of such societies to be persevering and persistent in their efforts. They are likely to focus on savings, conserve their resources, and invest in long term projects like housing.

Hofstede

Fons Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner, (1997) carried forward Hofstede’s analysis of national cultures and developed a cultural model with seven clear dimensions, namely (1) universalism v particularism, (2) individualism v collectivism, (3) neutral v emotional, (4) specific v defuse, (5) achievement v attentive, (6) synchronic v sequential and (7) external v internal control. Whilst Trompenaars (1997) model has some similarity with Hofstede’s dimensions, it adds dimensions in areas of achievement, time and control.

Browaeys and Price (2008) developed an elaborate model of national cultures in 2008, building upon and augmenting the theories of other experts. The authors argued that strategy was influenced by and influenced culture, thus making it imperative for modern-day managements to manage across national and cultural boundaries. Browaeys and Price (2008) reasoned that the international environment of modern-day organisations made it necessary for organisations to deal with various individuals of different cultural backgrounds in their role of clients, vendors, workers, government officials and regulators. It was thus vital for global managers to obtain suitable insights about the attitudes and approaches of diverse individuals in cross-cultural circumstances and adapt their management strategy accordingly, taking precautions to avoid the utilisation of similar approaches in all cases, or to use approaches that were suitable for particular circumstances in others (Browaeys & Price, 2008).

Browaeys and Price (2008) described eight significant cultural dimensions, namely (1) power, (2) competition, (3) time focus, (4) action, (5) time orientation, (6) structure, (7) communication and (8) space, and thereafter related these eight orientations with particular management activities like organising, planning, employing people, controlling and directing. This was the first attempt at directly relating management action with specific cultural traits (Browaeys & Price, 2008).

Time focus, one of the most important of cultural dimensions, is concerned with cultural approaches and attitudes towards time. The association of culture with time was first researched by Edward and Mildred Hall (1990), who developed concepts of monochronic and polychronic time. Whilst monochronic attitudes towards time represent the intense and restricted focus on only one specific issue at a time, polychronic attitudes towards time stand for a wider focus and attention to different things at the present time.

Browaeys and Price (2008) specifically focused on the relevance of polychronic and monochronic attitudes in the accomplishment of diverse organisational and managerial tasks. Monochronic cultures, for example, focused upon the management of tasks with the use of a calendar, whilst Chinese managers, who were essentially polychronic, did not even own calendars and functioned in far more flexible and improvised ways (Browaeys & Price, 2008). The requirement by a Chinese organisation for specific time-based performance in a joint venture was, in fact, likely to imply apprehension and mistrust towards partners (Browaeys & Price, 2008).

Whilst polychronic attitudes may appear to be unstructured and inefficient, it should be kept in mind that monochronic approaches work best in stable environments, wherein diverse stakeholders functioned consistently in monochronic ways, and where such environments were supported by a wider jurisdictional governance framework that provided clear and universally applicable procedures for all transactions. Monochronic strategies were, however, apt to be unsuccessful in environments where governance was carried out through constantly changing relationships, simply because such strategies did not have the flexibility required to react to constantly altering circumstances and environments.

Time focus also has significant implications for the management of knowledge. Clear facts and a number form the foundation of business activities and undertakings in monochronic cultures. The significance of such fact and numerical figures, however, takes precedence in polychronic cultures only for documents that are associated with prestige or status, like, for example, in annual reports or when engaging with stakeholders. Polychronic cultures feel the maintenance and enhancement of reputations to be more important than staying with the correctness of numerical data. Some experts have thus concluded that statistics provided by the Chinese may not be totally accurate.

Browaeys and Price (2008) stated that the behavioural patterns of people of monochronic and polychronic features are likely to be as indicated in the following table.

Predictable Patterns of Cultures of Monochronic and Polychronic People

Polychronic | Monochronic |

Two different activities are carried out side by side | Focus upon carrying out one activity at a time |

People are distracted and disturbed by external influences and events | Focus on their work |

Alter their plans often and easily | Are committed to time schedules |

Develop long term commitments and relationships | Stay with and are committed to plans |

Do not think of promptness as an important issue | Likely to have short term relationships |

Focus upon promptness |

Such cultural traits very obviously have significant implications for the management and functioning of business firms (Hofstede, 2001). Managers and executives who are used to function in monochronic cultures will in all probability find working with individuals from polychronic cultures to be extremely difficult (Hofstede, 2001). Employees from polychronic cultures may find difficult to focus on what is specifically told to them, which in turn can lead to disruption of planned activities (Hofstede, 2001). The lack of understanding between people of monochronic and polychronic cultures can result in various problems in areas of management, control and direction (Hofstede, 2001). It can lead to resentment and attrition in the workplace, cause tensions between supervisors and juniors, and have adverse outcomes in areas of productivity, effectiveness and efficiency (Hofstede, 2001).

Time orientation deals with the differences in the ways through which individuals view time, as well as its importance and role in their lives (Irwin, 2012). Anthropologists and cultural experts have stated that individuals inculcate their approaches and perspectives towards time through their social and cultural influences and backgrounds, as well as the value, beliefs and requirements of their societies and communities (Irwin, 2012). Such cultural influences shape their attitudes towards the future, as well as the present and the past (Irwin, 2012). Browaeys and Price (2008) have accordingly stressed upon the need for managements to know about the significance attached to particular elements of the wider time framework by people of specific cultures for the development of appropriate managerial policies.

Significant cultural implications also stem from the issue of context. Edward Hall’s theory of high and low context cultures assists in the understanding of culture on context, which essentially concerns circumstances in which communication take place (Nicholson, 2012). Low context cultures, which include those of the UK, the United States and many countries of Western Europe, are essentially linear, logical, focused on action, and individualistic in nature (Nicholson, 2012). Individuals from such cultures place significant value upon actual facts, logic, rationality, and direct approaches (Nicholson, 2012). The solution of problems in such cultures is mostly done by ascertaining various facts and by subsequently evaluating and assessing them (Nicholson, 2012). Decisions in such cultures tend to be based upon actual information, rather than upon gut-feel and intuition (Nicholson, 2012). Communication in such cultures is expected to be clear and is carried out with the help of precision in both speech and writing (Nicholson, 2012).

High context cultures, on the other hand, are essentially collectivist, contemplative and intuitive in nature (Irwin, 2012). The people of such cultures, which abound in Asia, Africa and South America, focus upon interpersonal relationships and feel trust to be the most important element in a business transaction (Irwin, 2012). The individuals of such cultures are governed more by intuition than by facts and prefer group harmony to individual achievement (Irwin, 2012). Communicators in such cultures are liable to make lesser use of legal documents or of precision in language (Irwin, 2012).

It is evident from the preceding discourse that national culture play very important roles in workplace behaviours and approaches, which makes it imperative for international managers to pay great attention to diverse cross-cultural issues and formulate and implement appropriate strategies in order to overcome associated problems and challenges (Nicholson, 2012).

Ethical and Commercial Challenges

China has in recent decades expanded enormously in economy activity. The Chinese economy has grown at an astonishing rate over the last three decades, making it the second-largest global economy after the United States (Kuijs, 2012). Whilst its low-cost workforce has helped in attracting a multitude of the western organisation to set up base in the country, its increasingly affluent population of 1.4 billion people has made the country an enormously attractive market for companies from across the globe (Kuijs, 2012).

Whilst China undoubtedly provides huge business opportunities in areas of both marketing and production, external businesses have to face numerous challenges and difficulties in the establishment of profitable and sustainable businesses in the country (Fan et al., 2006). China is a totalitarian, single-party rule, communist state, wherein the government has huge powers and takes an extremely active interest in all business affairs (Fan et al., 2006). The establishment of businesses by foreign companies specifically requires the permission of the government, which, however, is handled speedily and on a case to case basis (Fan et al., 2006).

It needs to be kept in mind that levels of corruption in China tend to be excessively high, and whilst the Chinese government and the country’s legal system does act strongly, and even harshly, towards people convicted of corruption, the absence of a free, vocal and critical media and the prohibition of dissent of any form is making the reduction of corruption very difficult (Lin, 2004). The country has been ranked 80th from the top with regard to corruption by Transparency International in 2012 (Irwin, 2012).

Such high levels of corruption pose specific problems for foreign organisations with regard to requests for bribes or other forms of gratification or enrichment in return for favours in areas of permissions and certificates (Irwin, 2012). Corruption is an extremely important issue for many large foreign businesses, not just because it is likely to be against their corporate governance stipulations but also because involvement in corruption in China and consequent conviction can lead to very strong penalties, including the imprisonment of senior officials and the cancellation of licence to conduct business in the country (Irwin, 2012).

Apart from the various problems and challenges associated with corruption, China also has significantly different political, legal, commercial and regulatory systems (Ward, 2010). It is important for all incoming organisations to obtain complete information about such systems and ensure that organisational operations are in complete adherence with local legal and regulating guidelines (Ward, 2010). It is important in this context to keep in mind that the country’s accounting and legal systems are still in a state of development and that it is not very easy to get high quality legal and accounting professionals (Ward, 2010). The absence of adequate and appropriate in-house expertise in legal and accounting areas could result in several types of commercial difficulties (Ward, 2010).

As discussed in the preceding section, China’s culture is characterised by high levels of masculinity, power distance index, and long term orientation (BCG, 2012). Whilst the country’s uncertainty avoidance is high, Chinese society is low on individualism and is highly collectivist in nature (BCG, 2012). Gender biases are also very strong and the proportion of females is significantly lower than that of males in the country (BCG, 2012). The Chinese culture is also the polychromic and high context in nature (BCG, 2012).

These diverse cultural traits are likely to lead to several types of workplace challenges, both ethical and otherwise, for western managers (Lin, 2004). The high degree of power distance implies that organisational employees in China would prefer clear reporting hierarchies and the assignment of specific responsibilities (Lin, 2004). It would be unlikely for such employees to show excessive initiative or go out of their way to ask for greater responsibility (Lin, 2004). It would also be extremely difficult for Chinese male employees to accept women as their equals in the workplace or to take directions from female bosses (Lin, 2004).

The polychronic culture of China implies that most Chinese employees will find it difficult to focus upon only one job at a time or to work with specific time frames (Ward, 2010). Such issues could result in significant difficulties for western managers to ensure timely completion of tasks (Ward, 2010). The high context culture implies that Chinese employees, both managers and others are likely to be uncomfortable in clearly detailed and explicit communication (Ward, 2010). Their communications, amongst themselves, as well as with their western counterparts, are likely to be far more ambiguous and contain lesser data than what is expected (Ward, 2010). Such communication practices may result in western managers feeling that they have not been provided with adequate information, even as the Chinese employees feel that the information is available for all to see and does not have to be rigorously detailed and defined (Ward, 2010).

Such differences in the cultures of western and Chinese employees can result in a number of challenges related to corporate governance, ethical issues and operational work (BCG, 2012). Western managers will find it most appropriate to develop a fair and equal workplace, where all employees are provided with equal opportunities in areas of selection, recruitment, training, assignment of responsibilities and career advancement (BCG, 2012). Chinese employees on the other hand are likely to find such organisational policies inappropriate (BCG, 2012). They would prefer to recruit people from their in-groups and expect the members of such in-groups to be provided with preferential treatment in all organisational areas (BCG, 2012). There could also be significant resistance, not to the employment of female workers, but to their advancement to senior organisational levels of responsibility and authority (BCG, 2012). With corruption levels in China exceedingly high and by and large accepted by many people, there is the distinct possibility of collusion between purchasing officials and suppliers, the ignoring of which could result in adverse organisational outcomes.

AB’s management will also have to give adequate care and thought to the basic product being manufactured by the planned joint venture (Alliance Boots, 2013). Alternative medicines are an integral part of traditional Chinese society. The formulations for these medicines often include animal parts and are not subjected to the extensive research and scientific rigour that is associated with the production of pharmaceuticals and medicines in western countries (Alliance Boots, 2013). AB very obviously has clearly developed rules and ethical codes of conduct in areas of medical research and testing, as well as in the formulation and production of pharmaceuticals and medical products (Alliance Boots, 2013).

It may be extremely difficult for the organisation to implement its accepted rules and processes in the area of alternative Chinese medicines, which have a totally different history of development, research and production. The production of these items could result in the development of huge ethical and governance challenges for the managers of the company’s proposed joint venture. The organisation has over the years developed an excellent reputation for adherence to ethics and quality in all its dealings. Such a reputation has, in turn, arisen from the organisation’s commitment to diverse rules, regulations and governance practices (Alliance Boots, 2013). It may be exceedingly difficult for the company’s management to replicate these rules for the production of alternative medicines, which are by and large based upon recipes that are widely accepted but have not been subjected to rigorous scientific analysis.

As evident from the preceding discussion, the organisational management of AB is likely to face several types of ethical and commercial challenges in the implementation of its proposed plan for the manufacture of alternative medicines in China. Whilst China is undoubtedly a huge economic power and provides enormous marketing opportunities, it has very different political, legal and regulatory environments. Incoming organisations are required to strictly adhere to governmental regulations with regard to foreign enterprises. The high corruption level of the country is also a source of extreme concern and can result in the development of diverse challenges and problems for western managers, both inside and outside the organisation.

The very different cultural backgrounds of Chinese employees can result in significant differences in perceptions about organisational work with regard to selection and recruitment of people, allocation of responsibilities, and career planning and advancement. Such cultural difficulties could also result in significant communication differences and lead to lack of understanding, resentment, organisational attrition and work disruption. The management of the company will also have to give significant thought to its actual production plan. The production of Chinese alternative medicines is very different from those of western drugs in areas of scientific research, testing and quality control; it may be extremely difficult for the company to enforce such practices for the production of alternative medicines.

Management Recommendations

The preceding chapters have dealt with the theoretical dimensions of national cultures, the ways in which cultural features of people differ from country to country, the impact of national cultures upon the attitudes and approaches of people, the different types of workplace challenges that can arise in multicultural workplaces where people of different cultures interact with each other, and the need to overcome such challenges for the achievement of organisational wellbeing and the realisation of organisational mission and objectives. Special attention has been given to the elaboration of the various ethical and commercial challenges likely to confront AB’s managers responsible for the development of the joint venture and its planned growth.

There is little doubt that the success of the venture will essentially depend upon the capabilities and expertise of the deputed managers, with specific regard to the handling of the project, the identification of diverse project, business and organisational challenges, and the successful overcoming of such challenges. The primary objective of the company should thus concern the selection of appropriate people for the handling of the organisation’s proposed project for the production of alternative medicines in China.

The people for this project will have to possess appropriate competencies and capabilities in diverse areas like project management, environmental management, production, marketing, and human resources management (Holden, 2002). With the salaries for Chinese employees likely to be significantly lower than those paid to western managers, the organisational management will have to decide between the cost economies of handling the business with Chinese employees, or the business effectiveness that is likely to be generated with the use of competent and experienced home office professionals (Holden, 2002).

It is recommended that AB should in the beginning develop a team of expatriate home office managers for handling different critical functions, like those of the Chief Executive Officer, the Chief Financial Officer and the heads for marketing, production and HR functions. The organisational strategy should entail the gradual and progressive development of a local management team that should be able to take over most of these responsibilities within a specified time frame, e.g. five or ten years (Denison, 2003). The adoption of such a strategy will allow the organisation to benefit from the various advantages of a highly specialised leadership, which will be vital for the achievement of success in the critical initial years, and at the same time develop a specific plan for the progressive ceding of responsibilities to competent local managers (Denison, 2003).

The selection and recruitment of an appropriate management team should be done with great care and thought (Robbins et al., 2008). Whilst it will undoubtedly be preferable to source such managers from inside the organisation because of their familiarity with organisational objectives, strategies and priorities, it is even more important to ensure that the chosen people are appropriately equipped and have both the competence and the approaches to handle their difficult responsibilities (Robbins et al., 2008). The management must thus ensure that the chosen few possess the necessary technical skills and abilities to carry out their allocated responsibilities and assignments (Robbins et al., 2008).

It is also equally important to ensure that such individuals are comfortable with functioning in foreign and international environments and have relevant experience of working in foreign locations and amongst people of different cultures (Gannon, 2004). They must essentially have broad and liberal outlooks and inherent respect for peoples of different cultures and nations (Gannon, 2004). It is thus important for the AB senior management to look carefully, both within and outside the organisation, and select the most appropriate people for the assignment, both in the technical and in the cultural context.

It will be necessary for the selected people to live in China with their families for extended periods of time and it should be ensured that difficulties do not arise later on this score. The organisation must take special care to ensure that the members of the selected team are remunerated appropriately and that suitable facilities and opportunities are provided to their family members in terms of housing, schooling, transportation, social life and entertainment (Adler & Gundersen, 2008). Unhappiness amongst family members or their discomfort with their Chinese milieu can result in domestic difficulties and tension and lead to inadequate performance, job dissatisfaction and the desire to be relieved of their responsibilities (Adler & Gundersen, 2008).

Whilst it is certainly important to choose people with suitable technical skills and cultural openness for this purpose, it is also equally important to provide them with an appropriate orientation about Chinese cultural issues and the diverse problems that are likely to arise in the workplace on this account (Redding & Stening, 2003). The managers must be fully aware of the various workplace issues that can arise because of the high power distance index of China, the long term orientation of the people, the immense emphasis placed upon collectivism and in-groups and the polychronic approaches of local employees (Redding & Stening, 2003). The appointed managers must take appropriate care to ensure the development of organisational structures that are appropriate for the local environment and do not result in undue stress upon employees (Redding & Stening, 2003). Whilst it is undoubtedly important for AB to implement standardised operating procedures, rules and regulations that are in sync with the head office, adequate care must be taken to ensure such rules and regulations are not imposed arbitrarily or cause undue resentment and confusion.

It is vitally important for managers to acquaint themselves with Chinese history and culture in order to obtain a better understanding of the environment and try to become as proficient as possible in Mandarin, the most widely used language in China (Brislin, 2008). It is also necessary for the western managers to be appropriately respectful towards and sensitive about local, cultural and religious issues (Brislin, 2008). The achievement of such an understanding and affinity for the local culture will help them in communicating effectively with Chinese employees and in the progressive implementation of standardised rules and regulations that will integrate the operations of the Chinese joint venture with the UK operations (Brislin, 2008).

It is important for the western managers to refrain from making assumptions when dealing with Chinese employees (Guffey, 2009). They should invite discussion, listen with attention, treat others with respect, and express empathy. Whilst numerous challenges undoubtedly exist in cross-cultural environments, the adoption of these simple methods will not only help in the development of rapport between the expatriate managers and local employees but also make the exercise enjoyable and educative for both sides (Guffey, 2009).

It is also extremely important for the management of AB to recognise the diverse ethical challenges that can arise in their Chinese joint venture and develop appropriate governance processes. The board of the company must lay down clear governance processes that prohibit local managers from engaging in specific activities like bribery, illegal ratification or unethical influencing of governmental authorities. Appropriate checks and controls, including internal audit measures, must be clearly laid down for all commercial activities, especially in areas of purchases, logistics management and inventories.

The organisational management must also develop and HR policy that is essentially based upon fairness and workplace diversity. Whilst it is undoubtedly important to understand and accommodate local cultural issues, it should also be ensured that the organisation does not get pressurised into adopting unfair or biased workplace practices on account of such pressures. The local management will have to clearly explain the organisational mission, as well as organisational values and beliefs to the local employees and communicate effectively about the need for implementation of diverse corporate governance and HR measures. There is little doubt that the careful implementation of these diverse strategies will help in the building of a productive, efficient and profitable organisation.

The corporate governance processes must also clearly detail the organisational approach towards the production of medical products and the existing organisational practices of detailed research and testing in order to ensure that the company’s products are able to provide the desired benefits. The management of the joint venture must accordingly aim to bring about an appropriate combination between established western methods of drug production and Chinese alternative medicine traditions in order to ensure that the firm’s products measure up to required production and quality standards. Whilst the adoption of these measures may result in some slowing down of the production process and slower product introduction, the adoption of such an approach will help in areas of consumer safety and organisational reputation.

Conclusions

This assignment aims to investigate, analyse, and assess the various challenges likely to be faced by the management of Alliance Boots in the area of cross-cultural communication during the implementation of the organisation’s proposed plan for a joint venture in China for the production of alternative medicines.

The report has been structured sequentially and first takes up the various cultural issues and factors that differentiate the cultures of the UK and China and the various cross-cultural communication problems that can arise because of such differences. The analysis reveals that the Chinese culture differs significantly from that of the UK in areas of power distance, collectivism, term orientation and focus upon time. It is, more specifically, high on power distance, long term orientation and collectivism. The Chinese culture is polychronic in nature, whereas the culture of the UK is essentially monochronic.

Such major cultural differences can result in significant divergence in the approaches and attitudes of western managers and Chinese employees. It is also more than likely that such differences will result in significant confusion, discontent, attrition and resentment with adverse organisational outcomes. Managers from the UK home office must therefore be carefully selected, not just with regard to their professional skills and expertise, but also their cultural openness and their ability and enthusiasm to work in foreign locations. These managers must also be provided with substantial orientation and training, possibly with the help of visits to China before the actual commencement of operations. They should also be carefully briefed about the various difficulties that are likely to arise in workplace communication on account of cultural differences and the most appropriate ways and means to overcome such differences.

This paper has dealt at some length with the various ethical and commercial challenges that can arise during the implementation of AB’s proposed project for alternative medicines. Such challenges may arise from the differences in the political, legal and regulatory environments of China and the UK, as well as the high levels of corruption in China. The company could also face organisational challenges on account of the significant gender bias for males in the country, as well as the preference for the Chinese people to work with members of their in-groups.

The senior management of AB must take special care to ensure the implementation of a clear and detailed corporate governance system that focuses on important issues like the ethical production of drugs, the prohibition of all types of illegal activities, especially the giving of bribes, and the development of a diverse and fair workplace. Whilst these measures may well lead to organisational discontent and resistance, they cannot be compromised for the sake of cultural sensitivity and the local management of the organisation will have to communicate effectively with employees to make them understand the importance of and need for such governance processes.

The careful and systematic implementation of these various recommendations should clearly help in the overcoming of various cross-cultural communication difficulties and in the establishment of an ethical, fair, harmonious and productive workplace.

References

Adler, N. J., & Gundersen, A., 2008, International Dimensions of Organizational Behaviour, Fifth Edition, South-WesternCENAGE Learning.

Alliance Boots, 2013, “About Us”, Available at: http://www.allianceboots.com/ (accessed May 31, 2013).

Barker, C., 2001, Cultural Studies, Theory and Practice, 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications.

BCG, 2012, “Overcoming the Challenges in China Operations”, Boston Consulting Group, Available at: knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/papers/…/BCG_SpecialReport2.pdf (accessed May 31, 2013).

Bluedorn, A. C., Kalliath, T. J., Strube, M. J., & Martin, G. D., 1999, “Polychronicity and the Inventory of Polychronic Values (IPV): The Development of an Instrument to Measure a Fundamental Dimension of Organizational Culture”, Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 14, no. 3–4, pp. 205–30.

Bodley, J. H., 1994, Cultural Anthropology: Tribes, states and the global system, Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

Boyd, M. H., 2009, “Hofstede’s Cultural Attitudes Research-Cultural Dimensions”, Available at: www.boydassociates.net/Stonehill/Global/hofstede-plus.pdf (accessed May 31, 2013).

Brislin, W. R., 2008, Working with Cultural Differences: Dealing Effectively with Diversity in the workplace, 1st edition, New York: Praeger Publications.

Browaeys, M-J., & Price, R., 2011, Understanding Cross-Cultural Management, 2nd edition, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Browaeys, M-J., & Price, R., 2008, Understanding cross-cultural management, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Denison, D., 2003, “The Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 119.

Fan, J., Morck, R., Xu, L. C., & Yeung, B., 2006, Does the quality of the government matter in attracting FDI: The China case in a Global Context, New York University: Mimeo.

Ferraro, G. P., 2002, The Cultural Dimension of International business, 4th ed. New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall.

Gagliardi, P., 2003, “Understanding Organizational Culture”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 133.

Gannon, M. J., 2004, Understanding global cultures: Metaphorical journeys through 28 nations, 3rd edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Guffey, M. E., 2009, Essentials of Business Communication, UK: South-Western/ Cengage Learning.

Hofstede, G., 1991, Cultures and Organisations: Software of the Mind, Intellectual Cooperation and its Importance for Survival, Harper Collins, pp. 79.

Hofstede, G., 2001, Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions, and Organisations across Nations, Second Edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G, & Hofstede, G. J., 2005, Culture and Organisations: Software of the Mind, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hall, E., 1976, Beyond Culture, New York: Doubleday.

Hall, E.T., & Hall, M. R., 1990, Understanding cultural differences: Germans, French, and Americans, Boston, MA: Intercultural Press.

Hofstede, G, & Hofstede, G. J., 2005, Culture and Organisations: Software of the Mind, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Holden, N. J., 2002, Cross-cultural Management: A Knowledge Management Perspective, Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Intel Reports, 2012, “US Intel report: India will overtake China as economic power in 2030”, Available at: http://www.news24online.com/us-intel-report-india-will-overtake-china-as-economic-power-in-2030_LatestNews24_7231.aspx# (accessed May 31, 2013).

ITim International, 2012, “Geert Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions”, Available at: www.geert-hofstede.com/ (accessed May 31, 2013).

Irwin, J., 2012, “Doing Business in China: An overview of ethical aspects”, Available at: www.ibe.org.uk/userfiles/chinaop.pdf (accessed May 31, 2013).

Jackson, T., & Artola, M., 1997, “Ethical beliefs and management behaviour: a cross-cultural comparison”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 16, pp. 1163-73.

Jeurissen, R.J.M., & Van Luijk, H.J.L., 1998, “The ethical reputations of managers in nine EU-countries: a cross-referential survey”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 17, pp. 995-1005.

Kaufman, C. F., & Lane, P. M., 1997, “Understanding Individual Information Needs: The Impact of Polychronic Time Use”, Telematics and Informatics, Vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 173–84.

Kaufman-Scarborough, C., & Lindquist, J. D., 1999, “Time Management and Polychronicity: Comparisons, Contrasts, and Insights for the Workplace”, Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 14, no. 3–4, pp. 288–312.

Kohls, J., & Buller, P., 1994, “Resolving cross-cultural ethical conflict: exploring alternative Strategies”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 13, pp. 31-8.

Lee, H., 1999, “Time and Information Technology: Monochronicity, Polychronicity and Temporal Symmetry”, European Journal of Information Systems, Vol. 8, pp. 16–26.

Lin, Y-M., 2004, Between Politics and Markets: Firms, Competition, and Institutional Change in Post-Mao China, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

McSweeney, B., 2002, “Hofstede’s model of national cultural differences and their consequences – a triumph of faith – a failure of analysis”, Human Relations, Vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 89-118.

Nelson, C. A., 1999, International Business: A Manager’s Guide to Strategy in the Age of Globalism, London: International Thomson Business Press.

Nicholson, N., 2012, “New report explores ethical challenges for business in China”, Available at: cwobserver.x.iabc.com/…/new-report-explores-ethical-challenge… (accessed May 31, 2013).

Redding, G., & Stening, B.W., 2003, Cross-cultural Management, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Robbins, S., Judge, T., & Sanghi, S., 2008, Organizational Behaviour, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Samovar, L. A., & Porter, R. E., 2004, Communication between Cultures, 5th Edition, UK: Thompson and Wadsworth.

Scarborough, J., 1998, The Origins of Cultural Differences and Their Impact on Management, Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Schneider, S. C., & Barsoux, J., 1997, Managing Across Cultures, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Solomon, M., 2011, Consumer Behaviour: Buying, Having, and Being, NJ: Pearson/ Prentice Hall.

Terpstra, V., & David, K., 1991, The Cultural Environment of International Business, Cincinnati, OH: South-Western.

Tjosvold, D., & Leung, K., 2003, Cross-cultural management: foundations and future, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

Transparency International, 2013, “Corruption by Country / Territory”, Available at: http://www.transparency.org/country (accessed May 31, 2013).

Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C., 1997, Riding the waves of culture: understanding cultural diversity in business, London: Nicholas Brealey.

Ward, J., 2010, “Ethically Doing Business in China”, Available at: http://robinson.gsu.edu/resources2/files/ethics/goodbusiness/ethically.html (accessed May 31, 2013).

Weber, Y., Belkin, T., Tarba, S.Y., 2011, “Negotiation, Cultural Differences, and Planning in Mergers and Acquisitions”, Journal of Transnational Management, Vol. 16, no.2, pp. 107-115.

Yintsuo, H., 2007, “Relationships between National Cultures and Hofstede Model, and Implications for A Multinational Enterprise”, Proceedings of the 13th Asia Pacific Management Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 1422-1428.

More From This Category

Actions and Behaviour of Employees at Work

Notwithstanding the evolution of management theory and practice towards control of employee behaviour, failures in controlling of employee behaviour keep on happening and are considered to be one of the main reasons behind the continuing difficulties in the management of change. This area of organisational behaviour continues to attract significant attention.

Human Resource Management: Get the Best of both Worlds by Combining Learning and Development

It is imperative to consider the intricacy and assortment of training in order to validate the criticality of comprehending the distinct learning and developmental requirements of employees in the preparation of suitable training and development packages

How to Create an Organisation where Employees Behave

Notwithstanding evolution of management theory and practice towards control of employee behaviour, failures in controlling of employee behaviour keep on happening and are considered to be one of the main reasons behind the continuing difficulties in management of change

0 Comments