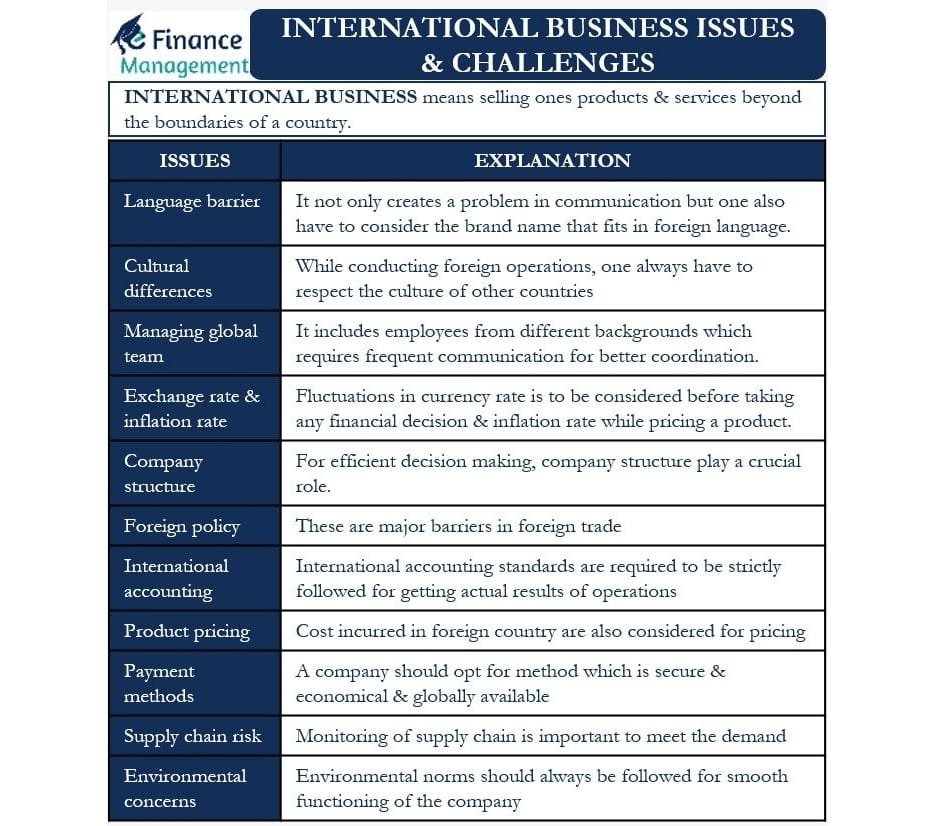

Cultural and Linguistic Challenges in International Business

2021

Introduction

This study deals with the cultural and linguistic challenges faced by organisations engaged in international business activities; it attempts to discuss the ways in which contemporary multinational corporations (MNCs) attempt to cope with linguistic diversity and assess the problems that arise from the adoption of such strategies.

Recent decades have witnessed substantial expansion in international business activity, a phenomenon that has primarily been led by Anglo-American and other Western MNCs (Adler & Gundersen, 2008). Diverse geo-political and economic developments, like the deconstruction of the Soviet Union, the coming together of Germany, the formation of the European Union and economic liberalisation in the developing world have resulted in acceleration of globalisation and the generation of business opportunities across the world, especially for firms with adequate resources to engage in international expansion (Adler & Gundersen, 2008).

Management academics and practitioners are in complete agreement over the significance of employees in enhancement of organisational productivity and achievement of organisational success. Employees are in fact considered to be the most critical of organisational assets for enhancement of competitive advantage. The need for controlling employee behaviour and output was taken up in detail by management experts like Fredrick Taylor, Fayol and Ford in the first quarter of the 20th century. Their research and ideas resulted in the development of scientific management principles and a linear, managerialist and authoritarian approach to employee control.

MNCs and even other firms with more restricted operations have responded to these opportunities by expanding their international business swiftly and substantially (Harzing et al., 2011). It must however be recognised that attempts at international expansion have resulted in significant challenges for internationalising firms in areas of environmental management and cultural and linguistic diversity (Harzing et al., 2011).

MNCs have become exposed to various cross-cultural challenges, stemming from differences in the national cultures of their home and host locations and the linguistic diversity of their geographically dispersed operations (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a). These corporations have adopted several types of strategies for managing these challenges, some of which have in turn resulted in the development of other problems (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999b).

This short essay attempts to discuss the various issues stemming from cultural and linguistic diversity in the contemporary globalising world, the strategies adopted by MNCs and the various issues that can stem from the adoption of such strategies.

Cross Cultural Issues

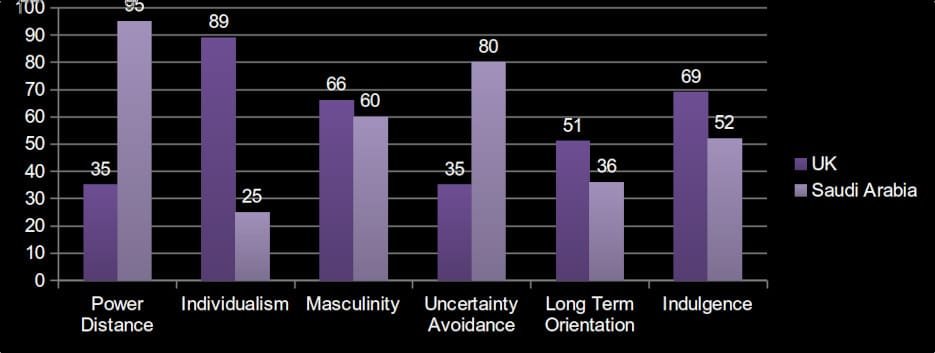

The internationalisation of business operations inevitably results in the entry of firms into various geographically distant locations, each with its unique environmental features (Hofstede, 1983). The overwhelming majority of such geographical targets have distinctive national cultures, with distinct cultural attributes that influence and shape the attitudes, approaches and actions of their residents, both in their personal lives and in the workplace (Hofstede, 2001). The study of national cultures was initiated by Geert Hofstede, who studied the cultures of different nations from the early 1970s and found that people of different countries, and even different regions, differed from each other, with particular regard to four specific cultural attributes, i.e. individualism v collectivism, masculinity v femininity, power distance and uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, 1983).

Hofstede has subsequently augmented his theory on national culture by adding two more dimensions, namely long term v short term orientation and indulgence v restraint. These six dimensions of national culture are explained in greater detail below:

Individualism v Collectivism

Individualism can be described as a preference for a social framework, wherein individuals are expected to take care of their immediate families and themselves (Hofstede, 2001). Collectivism on the other hand concerns a framework that is tighter and where individuals are looked after by larger in-groups in exchange for loyalty (McSweeney, 2002). Social position on this dimension concerns the reflection of self-image in terms of “I” or “we” (McSweeney, 2002).

Masculinity v Femininity

Inherently masculine cultures focus upon competitiveness, heroism, achievement, assertiveness and material rewards (Hofstede, 1983). Feminine cultures show greater preference for caring, cooperation, modesty, quality of life and consensual work (Hofstede, 2001).

Uncertainty Avoidance

This cultural dimension concerns the level to which members of society are comfortable with ambiguity, uncertainty and lack of clarity. Cultures with low uncertainty avoidance scores are relaxed in their attitudinal knowledge and are willing to accept new developments, ideas and thoughts (Hofstede, 1983). The people of countries with strong uncertainty avoidance indices are on the other hand characterised by rigid beliefs, strong behavioural codes and intolerance for new ideas or unorthodox behaviour (McSweeney, 2002).

Long Term v Short Term Orientation

Members of societies with high long term orientation focus upon achievement of long term benefits, encouraging thrift and the development of skills and abilities to prepare for the future (Hofstede, 2001). The people belonging to cultures with short term orientation on the other hand view societal change with suspicion and are more focused on short term benefits like status and material rewards (Harvey, 1997).

Indulgence v Restraint

Indulgent societies allow freer gratification of human drives concerning enjoyment and having fun (Hofstede, 1983). Restraint in cultures on the other hand is evidenced by suppression of need gratification and its regulation through strict social norms (Harvey, 1997).

The following chart provides details about cultural differences between the UK and Saudi Arabia:

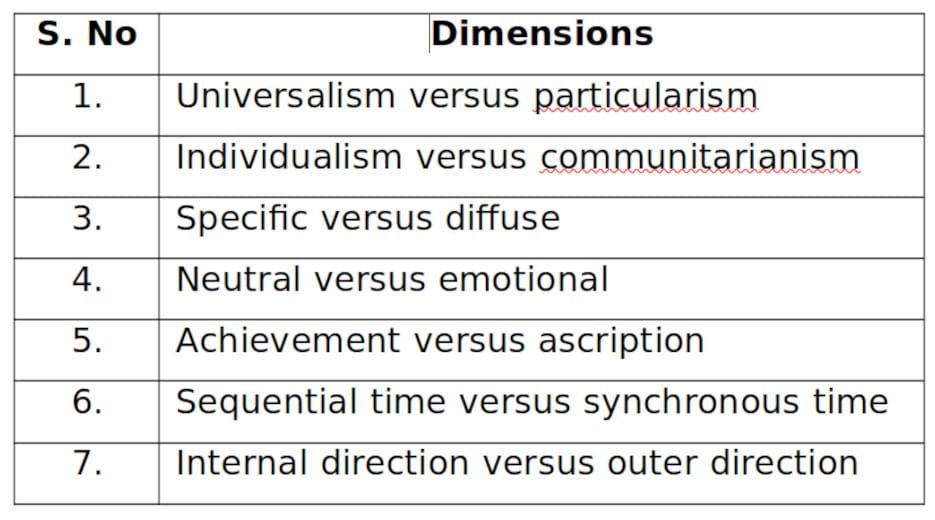

Hofstede’s work on the distinctiveness of national cultures has been augmented by the work of experts like Fons Trompenaars and by the evolution of concepts like monochronic and polychronic societies (Trompenaars, 1993). Trompenaars (1993) augmented Hofstede’s theory on national cultures by developing the seven-dimension cultural model, wherein he stated that cultures were distinguished by 7 specific attributes, as elaborated in the table provided below.

Some of Trompenaars’ dimensions, such as individualism v communitarianism are similar to Hofstede’s dimensions, e.g. individualism v collectivism, whereas others are different (Ferraro, 2002). His dimension on sequential v synchronous time has been elaborated in greater detail through the exposition of monochronic v polychronic cultures (Communicaid Group Ltd, 2010). The monochronic time system, which is similar to sequential time and is common to countries like the USA and the UK, is characterised by the preference for doing things one at a time; time is segmented in this system and thereafter scheduled, arranged and managed (Browaeys & Price, 2008). Polychronic cultures on the others hand reveal the preference for doing several things together and approaching time scheduling with a more fluid approach (Communicaid Group Ltd, 2010).

The efforts of experts like Hofstede and Trompenaars have resulted in the growing appreciation of cultural attributes and the distinctive features of national cultures (Shimoni & Bergman, 2006). Smith (1992) stated that differences in national cultures can significantly affect the working of international business. He stated that the growing global diversity of business transactions can result in greater chances of national cultural conflict between different groups within international business environments (Smith, 1992). Cultural differences can also result in difficulties in communication between two sets of people within MNCs and other international organisations, especially between the employees of home and host countries (Shimoni & Bergman, 2006). The presence of significant differences between the national cultures of home and host countries can result in problems of acceptance, implementation and operational effectiveness (Shimoni & Bergman, 2006).

It has been seen that whilst people from different cultures often appear to exhibit similarity in behaviour and cultural backgrounds, such similarities are often superficial and actual cultural expectations can well be divergent (Snow et al., 1996). Several issues thus need to be addressed by MNC managements in order to reduce and minimise the chances of conflict from cultural disagreements between employees of different countries (Nardon & Steers, 2008). Research has revealed that employment of local operatives in foreign subsidiaries can help in reduction of tension stemming from clashes in national culture and enhance organisational change (Laurent, 1983).

The employment of local people by MNCs has been growing steadily over the last two decades (Shimoni & Bergman, 2006). Whilst the adoption of such a strategy has been seen to be of help in the development of several positive outcomes, like (a) the reduction in placement of expensive expatriates in various global locations, (b) the utilisation of local talent, (c) the achievement of greater understanding of local issues and difficulties and (d) the development of truly diverse organisations, it has also resulted in the development of intra-organisational, cross-cultural challenges, which need to be identified and overcome by the adoption of appropriate management and Human Resource (HR) strategies (Mellahi & Collings, 2010). Experts like McGregor and Hamm (2008) and Morgan et al., (2003) have recommended that MNCs should adopt clearly formulated and well articulated HR strategies for overcoming such cross cultural challenges, which should be based upon respect for all cultures and the adaptation of HR and management strategies to suit local conditions, as well as the attitudes and approaches of local employees.

Linguistic Diversity and Resultant Organisational Challenges

The study of available literature revealed that internationalisation of business resulted in the entry of business organisations in diverse target countries with significant linguistic differences.

CHART 3: LANGUAGE, INCLUSION, AND DIVERSITY IN THE WORKPLACE (Source: Russell, 2018)

Such linguistic differences result in the development of various types of operational challenges and difficulties. Academic research on internationalisation has focused primarily on overcoming of cultural challenges and neglected the organisational problems that can arise from linguistic divergence. Adler and Gundersen (2008) have stated that the importance of managing cross-cultural challenges appears to have blinded academics and researchers to an important country-associated issue with similar impact, namely differences in national languages.

All MNCs operating in a fast globalising environment have to find ways and means to deal with and overcome the language barriers encountered by them in the course of their expansion into countries that do not share the language of home countries (Vaara et al., 2005). Whilst MNCs in previous days primarily expanded into culturally proximal destinations, in line with the Uppsala theory of internationalisation, and were not overly burdened by the need to work in extremely different linguistic environments, contemporary MNCs have to perforce establish markets and operations in countries with diverse linguistic characteristics (Nardon & Steers, 2008). Recent decades have witnessed the steady reduction in economic growth in the advanced western economies, which have, until now, and for much of the 20th century, driven global economic growth and activity (Harvey, 1997). The saturation of the economies of the advanced nations and the gradual setting in of economic stagnation in these countries has been accompanied, on the other hand, by sharp and continuous increase in economic activity and growth in the emerging and developing nations, especially in Asia and to a certain extent in South America (Nardon & Steers, 2008).

The economic reforms in China, which were initiated in 1979 and thereafter followed up with great vigour, resulted in sharp economic growth in the PRC, evidenced by double digit GDP expansion for the major portion of three decades (Dupuis & Prime, 1996). Significant economic expansion has also occurred in the other BRICS nations, namely Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa, the Middle Eastern nations, Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, and in countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nigeria (Harzing et al., 2011).

Whilst the overwhelming majority of MNCs are headquartered in the United States, the UK, some West and North European countries and Japan, they are establishing markets and production facilities in the emerging and developing countries with very different linguistic environments (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a). The main language spoken in China is Mandarin, which is very different from English and other European languages (Vaara et al., 2005). Whilst English is spoken by the elite in India on account of its colonial past, the majority of Indians speak Hindi and a variety of other Indian languages. Swahili is commonly spoken in Africa, whilst the countries of Southeast Asia and Bangladesh also have their individual languages, which are very different from English, French or German (Vaara et al., 2005). It also needs to be appreciated that countries like India and China, as well as the African continent have a variety of regional languages and dialects that are commonly used in different states (Harzing et al., 2011).

Internationalising organisations thus have to establish their operations in working environments characterised by different languages (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a). Such differences between the languages of home and host locations result in several types of communication problems in organisational interaction with suppliers, customers, governmental authorities, regulators, local partners and employees (Harzing et al., 2011). It needs to be appreciated that the existence of various types of cultural differences in areas like individualism v collectivism, masculinity v femininity, uncertainty avoidance, power distance and long term orientation makes it difficult for the officials and managers of organisational headquarters of MNCs to communicate effectively with stakeholders in host destinations (Harzing et al., 2011). Such difficulties are compounded significantly by the existence of linguistic differences (Harzing et al., 2011). The presence of such linguistic differences results in the creation of several types of challenges in both internal and external communication (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a). Home country managers must, especially at the initiation of businesses in new international locations, communicate effectively with a variety of stakeholders like suppliers, governmental authorities, regulators, customers and local employees effectively in order to establish efficient and productive international operations (Harzing et al., 2011). The presence of linguistic differences thus results in the development of significant challenges and barriers to such communication (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a).

Organisational Strategies for Management of Linguistic Challenges

Organisational managements are implementing a number of strategies and approaches to overcome language barriers in business activity (Neeley, 2012). One of the most important developments in this area has been the growth of English into a widely accepted global channel of communication (Neeley, 2012). Whilst the use of English was introduced and implemented across the world by British colonialism, it was subsequently popularised in business communication, especially after the close of the Second World War, on account of the ascendancy and expansion of American and English business corporations across the world (Harzing et al., 2011). The development of English as a common link language in the majority of countries has resulted in it being increasingly taught in schools and colleges, as also in its greater use in business communication and correspondence (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999b).

The officials of internationalising organisations and a variety of stakeholders in different countries thus often speak in English with each other (Harzing et al., 2011). It is not uncommon for an Indonesian manager working for a German MNC to communicate with Indian suppliers in English (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a). The overwhelming majority of business organisations are thus advocating and insisting upon English for all organisational activities, thereby restricting the inefficiencies of unrestricted multilingualism (Neeley, 2012).

Most management institutions across the world, regardless of their country of location conduct their academic instruction in English, especially where the student body is distinctly international in its constitution (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a). Such an educational and academic strategy, which is being adopted by management education institutes in various non-English speaking countries, is also helping in developing an international management community that is comfortable in communication in English (Neeley, 2012).

Apart from focusing upon reinforcing English as the language of communication, the majority of internationalising businesses are actively employing local citizens for their work across departments and organisational levels (Neeley, 2012). Such employment helps these organisations in reducing the costs of expatriate managers, exploiting local talent and using the cultural and social knowledge of their local employees in a variety of organisational operations, especially in communication with various types of local stakeholders (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a). Harzing et al., (2011) stated that contemporary MNCs attempt to overcome their language barriers through the adoption of various strategies like (a) building in redundancy by repeating information several times during communication, (b) adjusting the mode of communication, like switching from telephone calls to emails, (c) the adoption of a common corporate language, which by default is English in many countries across the world, (d) imparting of language training and (e) use of external translators or interpreters. Many organisations take the help of bilingual employees to develop communication channels with local people and hire non-native managers, who are familiar with both cultures (Harzing et al., 2011).

Impact of Adoption of such Strategies upon Organisational Work Processes

MNCs, as evident from the preceding discussion, make use of several types of strategies to overcome language barriers, ranging from the adoption of a specific language for communication to the use of bilingual employees and accessing of services of interpreters and translators (Harzing, 2003). These solutions are however not foolproof and have their individual advantages and limitations (Harzing et al., 2011). The adoption of a common language, which is often English, can result in significant resistance and objections from organisational employees, especially from people not very conversant with the common language (Maclean, 2006). The adoption of a common language for communication can also result in the development of several types of misunderstandings and the hardening of group identities (Maclean, 2006).

The use of translators and interpreters on the other hand is bound to be inconvenient, expensive and not really suitable for several organisational issues that may relate to business strategies and be confidential in nature (Harzing & Feely, 2008). The utilisation of bilingual employees can help in resolving some communication problems but could also result in the development of informal power centres and in chances of misrepresentation of information, both intentional and unintentional (Harzing & Feely, 2008). The use of local non-native managers could be useful in overcoming language barriers, but it may be difficult to locate such managers with ease (Harzing & Feely, 2008).

Conclusions and Recommendations

The conduct of this study, which aimed to examine the cultural and linguistic difficulties and challenges faced by multinational corporations, revealed that internationalising organisations were bound to face several types of operational challenges on account of linguistic differences between their home and host countries. Whilst contemporary MNCs were attempting to overcome such challenges through the adoption of several types of strategies, none of these strategies could be considered to be optimal for overcoming language associated barriers.

Harzing et al., (2011) found that the institution of a corporate language and the utilisation of language training were very common in MNCs. The appointment of employees with good English speaking skills has also been found to be useful in enhancing local communication (Harzing & Feely, 2008). Several experts have stated that contemporary organisations must essentially understand the implications of language barriers and be ready to use different types of stratagems, like building in redundancy, adjusting communication modes, using bilingual employees, employing individuals with good English language skills and the adoption of a common corporate language to overcome language barriers. The development of an appropriate mix of these strategies must however be decided upon by organisational managements, with regard to their individual circumstances, in order to obtain the best possible results.

References

Adler, N.J., & Gundersen, A., (2008), International Dimensions of Organisational Behavior, Case Western Reserve University: Thomson.

Browaeys, M-J., & Price, R., (2008), Understanding cross-cultural management, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Communicaid Group Ltd, (2010),” Cross-Cultural Communication Styles: High and Low Context”, Available at: http://www.communicaid.com/cross-cultural-training/blog/cross-cultural-training/high-and-low-context/ (accessed October 14, 2021).

Dupuis, M. & Prime, N., (1996), “Business Distance and Global Retailing: A Model for Analysis of Key Success/Failure Factors”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 24, Iss (11): pp. 30–38.

eFinance.com, (2018), “International Business – Issues and Challenges”, Available at: https://efinancemanagement.com/international-financial-management/international-business-issues-and-challenges (accessed October 14, 2021).

Ferraro, G. P., (2002), The Cultural Dimension of International business, 4th ed. New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall.

Hartmann, E., Feisel, E., & Schober, H., (2010), “Talent management of western MNCs in China: Balancing global integration and local responsiveness”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 45: pp. 169–178.

Harvey, F., (1997), “National cultural differences in theory and practice: Evaluating Hofstede’s national cultural framework”, Information Technology & People, pp. 132-146.

Harzing, A.W.K., (2003), “The role of culture in entry mode studies: from negligence to myopia?”, Advances in International Management, Vol. 15: pp. 75-127.

Harzing, A.W.K., & Feely, A.J., (2008), “The Language Barrier and its Implications for HQSubsidiary Relationships”, Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, Vol. 15, Iss (1): pp. 49-60.

Harzing, A-W., Koster, K., & Magner, U., (2011), “Babel in business: The language barrier and its solutions in the HQ-subsidiary relationship”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 46: pp.279–287.

Hofstede, G., (1983), “The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 14: pp. 75-89.

Hofstede, G., (2001), Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviours, institutions and organizations across nations, 2nd edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kedia, B. L., & Mukherji, A., (1999), “Global managers: developing a mindset for global competitiveness”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 34, Iss (3): pp. 230–251.

Laurent, A., (1983), “The Cultural Diversity of Western Conceptions of Management”, International Studies of Management and Organization, Vol. 13, Iss (1/2): pp. 75-96.

Maclean, D., (2006), “Beyond English, Transnational corporations and the strategic management of language in a complex multilingual business environment”, Management Decision, Vol. 44, Iss (10): pp. 1377-1390.

Marschan-Piekkari, R., Welch, D.E., & Welch, L.S., (1999a), “In the Shadow: The Impact of Language on Structure, Power, and Communication in the Multinational”, International Business Review, Vol. 8, Iss (4): pp. 421–440.

Marschan-Piekkari, R., Welch, D.E. & Welch, L.S., (1999b), “Adopting a Common Corporate Language: IHRM Implications”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 10, Iss (3): pp. 377–390.

McGregor, J., & Hamm, S., (2008), “Davos Special Report: managing the global workforce, BusinessWeek, pp. 34–43.

McSweeney, B., (2002), “Hofstede’s model of national cultural differences and their consequences”, Human Relations, Vol. 55: pp. 89–118.

Mellahi, K., & Collings, D. G., (2010), “The barriers to effective global talent management: The example of corporate elites in MNEs”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 45: pp. 143–149.

Morgan, G., Whitley, R., Sharpe, D., & Kelly, W., (2003), “Global Managers and Japanese Multinationals”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 14, Iss (3): pp. 389-407.

Nardon, L., & Steers, M. R., (2008), “The new global manager: Learning cultures on the fly”, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 37, Iss (1): pp. 47-59.

Neeley, T. B., (2012), “Global Business Speaks English”, Harvard Business Review, Available at: http://innovationinthebox.com/clientresources/articles/Global%20Context/Gobal%20business%20speaks%20English%20HBR.pdf (accessed October 14, 2021).

Russell, L.E.M., (2017), “Language, inclusion, and diversity in the workplace”, Available at: https://hrdailyadvisor.blr.com/2017/12/17/language-inclusion-and-diversity-in-the-workplace/ (accessed October 14, 2021).

Shimoni, B., & Bergman, H., (2006), “Managing in a changing world: from multiculturalism to hybridization”, Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 20: pp. 76-89.

Smith, P., (1992), “Organizational behaviour and national cultures”, British Journal of Management, Vol. 3: pp. 39-51.

Snow, C., Snell, S., & Davison, S., (1996), “Use Transnational Teams to Globalize Your Company”, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 24: pp. 50-67.

Trompenaars, F., 1993, Riding the Waves of Culture, London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing Ltd.

Vaara, E., Tienari, J., Piekkari, R., & Säntti, R., (2005), “Language and the Circuits of Power in a Merging Multinational Corporation”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 42/3: pp. 595-623.

More From This Category

Actions and Behaviour of Employees at Work

Notwithstanding the evolution of management theory and practice towards control of employee behaviour, failures in controlling of employee behaviour keep on happening and are considered to be one of the main reasons behind the continuing difficulties in the management of change. This area of organisational behaviour continues to attract significant attention.

Human Resource Management: Get the Best of both Worlds by Combining Learning and Development

It is imperative to consider the intricacy and assortment of training in order to validate the criticality of comprehending the distinct learning and developmental requirements of employees in the preparation of suitable training and development packages

How to Create an Organisation where Employees Behave

Notwithstanding evolution of management theory and practice towards control of employee behaviour, failures in controlling of employee behaviour keep on happening and are considered to be one of the main reasons behind the continuing difficulties in management of change

0 Comments