Inclusion of Networking for Women and Minority Group Members in the Workplace

Introduction

Networks are critical organisational elements, both in the public and private sector. These networks comprise the web of relationships, both formal and informal created to get things done (Ibarra, 1993). Such networks support the many functions that individuals fulfil at work from the completion of routine transactions to socialising, innovating, planning, learning and career development (Raj et al., 2017). All organisational participants should to be part of these networks and use them for a variety of purposes, including career advancement, climbing in the organisation and taking on more responsibilities.

Women and members of minority groups however find it difficult to access these networks. These problems lead to considerable disadvantages and challenges in achievement of organisational equality and inclusion, as well as opportunities for rising in the organisation, entering the senior echelons of management, assuming greater responsibilities and finding success in their careers (Rumens, 2011).. Awareness about the need for ensuring access to networks for all organisational employees, regardless of their gender or their ethnic/religious/cultural origin is, however, increasing and leading to the adoption of required organisational strategies, decisions and systems (Armstrong, 2019).

Organisational Networking and its Importance

The significance of effectual and strong professional networks cannot be underestimated. Such networks assist organisational members to fit into the company’s structure and culture; they assist network members in staying up-to-date with what’s going on and enable them to participate in discussions on work related issues and relationships. Effective networks help firms in adapting swiftly to organisational change, whereas the quality of people’s networks influence the quality of their decisions. Effective leaders thus tend to cultivate organisational networks in specific ways. As organisational culture is specifically embedded in a firm’s network; these networks can effectively resist or enable cultural change. Networks as such need to integrate well after mergers and acquisitions. Failure in the achievement of such integration can result in underachievement of desired synergies or cost savings in the post M&A phase.

Participation in networks helps in creation of social capital for employees, which can drive career advancement and improve job satisfaction. This is facilitated by two specific phenomena, namely informal networking and sponsorship. Informal networks can be described as social relationships that are formed between colleagues in several face-to-face ways, like meeting over lunch and coffee, participating in sports teams, engaging in weekend cycling challenges or just socialising in the bar after work They are quite important for getting noticed for promotion. Individuals can make use of such networks to know people who are more senior to them but who do not work directly with them (Carter & Silva, 2010). This makes it likely for such employees to access greater opportunities to join a project or be invited to apply for a promotion. Discussions about work frequently occur in these more informal settings and such discussions influence decisions that are subsequently taken in official meetings (Hewlett, 2013).

Getting to know a wider group of people in the organisation also infers that someone is likely to come to mind during the making of lateral appointments. Individuals can know a bigger group of people either through informal conversations or by joining networking events. Whilst networking is primarily an issue for individuals, organisations can also contribute by helping in the development of communities around common goals, objectives and interests (Raj et al., 2017). With regard to sponsorship, participation in networking helps in the development of sponsors/ advocates. Sponsors can talk to others about an individual’s strengths and potential and assist in their development opportunities, lateral movement or promotion (Hewlett, 2013). A sponsor is likely to use his or her social capital and resources on behalf of a particular individual. A sponsor can also assist an individual in adjusting and succeeding in an unfamiliar and stretching role.

A sponsor can not only help in keeping people with talent in an organisation but also be instrumental in considerable enhancement in promotions, pay increases and stretch assignments for protégés. Sponsorship occurs in an informal way when people in leadership positions discuss about particular employees who could fit into specific opportunities. Such an informal system of patronage can be considered to be a small step from socialising with and supporting those who share the sponsor’s interest. It can be inferred that unconscious and even unintentional bias works in such situations; unconscious bias actually thrives in an informal and unstructured environment free of balances and checks. Biased decisions favour particular groups at the expense of others and women, as well as members of minority groups face the risk of missing out on sponsorship opportunities that can result in rear enhancement. It can thus be specifically seen that participation in organisational networks can be critically important for achievement of career advancement, accessing senior echelons of management and achieving success in the workplace. It can accordingly be concluded that fair organisations should provide all employees, including women and members of minority groups, access to workplace networks, both formal and informal.

Challenges Faced by Women and Minority Group Members in Accessing Organisational Networks and Consequent Problems

One of the most frequently reported difficulties faced by women and racial minorities in contemporary organisations is restricted access to or even exclusion from informal interaction networks. This results in multiple disadvantages, including restricted knowledge of what is going on in the formation of alliances and consequent difficulties in mobility and breaking through the glass ceiling.

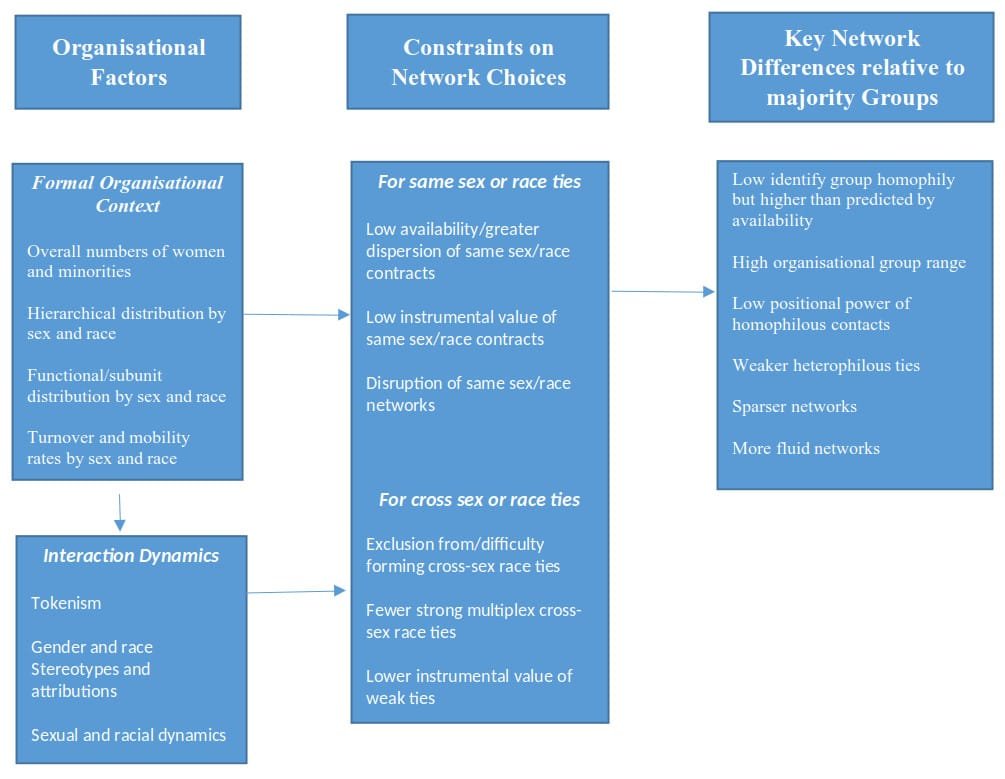

The embedding of interaction patterns in the organisational context constitutes a primary reason for gender and race differences in network patterns. Social relationships take place within an opportunity context that either prevent or facilitate diverse types of social contact. Whilst people tend to interact with others who are similar in socially important ways, such a tendency can be subjected to considerable constraints on account of lack of availability of similar others within the social groups to which individuals belong. Other various dimensions on which similarity can be evaluated furthermore tend to be strongly correlated with the result that participants of specific demographic groups tend to belong to specific organisational groups, compared to others. High levels of correlation result in greater social distancing from members of other groups, thereby resulting in restricted opportunities for interaction. The context of opportunity in an organisation is by and large defined by an organisation’s demography or its formal structure. Some specific issues are relevant in this context, namely the degree to which women and racial minorities are present in the specific organisational context, the extent to which women and members of minority groups are represented in upper organisational echelons, the notch to which departmental or functional groups are segmented by gender or ethnicity such that group members are either systematically over represented or underrepresented in specific subunits, and finally the turnover and mobility rates of women and minorities compared to members of majority groups.

The exclusion of women and members of minority groups from interaction networks is frequently associated with a universal tendency for preferred interaction with other people of the same sex or ethnic background. Women and members of minority groups generally have a comparatively smaller set of similar other people with whom professional networks can be developed on the basis of homophilous interaction. It is well accepted that the personal networks of male and female entrepreneurs tend to consist mostly of men. Research has revealed that ties across races and gender tend to be considerably weaker than homophilous relationships in both peer and senior junior relationships; this constrains members of minority groups and women in accessing organisational networks in significant measure.

An organisation’s opportunity context is actually similar to the larger social system and direct and indirect access to personal networks structures. Personal networks are considerably influenced by preferences and stereotypes that are strengthened by structural issues and restrict the abilities of women and minority group members to develop heterophilous connections. Research has revealed that the numerical composition of the upper echelons of firms leads to different contexts for interaction for majorities and minorities.

Structural Constraints on Properties of Women’s and Racial Minorities’ Interaction Networks

Women face several informal challenges in accessing networks. Even if a person is in, she may not be excluded from general conversations, but will not be thought of when significant events are discussed or unofficial outings are organised. Women often do not realise that they need networks and unrealistically assume that formal structures will lead to their advancement into leadership roles.

Measures for Improvement of Networking Amongst Women and Minority Group Members

Several procedures can be adopted to improve network access to women and members of minority groups. Organisations can identify hosts for work related occasions, who can welcome women and minority group members and introduce them to others. Team leaders should charge their teams to take tea or coffee breaks to meet someone who is new to them, ideally a person belonging to a different gender or minority group. People who are new to the group should be specifically tasked with having coffee with 10 people they do not already know over the first 10 weeks. Team events and celebrations should be creatively organised to purposely include women and people from minority groups. Lunching at one’s own desk should be banned and people should eat in social spaces where they can chat and get to know other people. New people should be taken by seniors to clients events in order to introduce them to important stakeholders.

Diversity networks help in enhancement of equality and inclusion in organisations. They have grown to be popular instruments for the promotion of organisational equality. These internal networks are initiated to generate and promote organisational equality by informing, supporting and advancing employees with historically marginalised social identities. Research has specifically indicated that diversity networks can positively impact on the career prospects of women, ethnic minorities and LGBT employees; they can facilitate safe spaces for members for the sharing of experiences and provide opportunities to discuss with management on equality and diversity related issues. Diversity networks help in enhancing the number of historically marginalised employees in organisations and improve their representation in managerial ranks. These networks can again comprise specifically of women, ethnic minorities and LGBT employees and work towards enhancement of equality and inclusion.

Conclusions

Modern businesses continue to be dominated by men of the majority community, despite increasing entry of women and members of minority groups. Research has revealed that members of this group tend to, both intentionally and unintentionally interact with people of their own groups on account of homophilous reasons, thereby excluding access to women and members of ethnic minorities.

This results in considerable disadvantages for the excluded groups because network occurrences and dynamics often result in formal decisions for promotions, inclusion in new projects and giving of new responsibilities. Exclusion from networks dominated by the majority group adversely impact the opportunities available to women and ethnic minority group members from progressing in the organisation, moving to the glass ceiling, taking up additional responsibilities and achieving success in their careers. Whilst women and ethnic minority group members have historically been excluded from organisational networks, growing awareness about the basic unfairness of this process has led to the adoption of several corrective measures by organisational managements. These include the creation and use of diversity networks in organisations, as well as the practical application of various methods to ensure greater participation of women and people from minority groups in organisational activity. Notwithstanding the difficulties faced by the members of excluded or semi-excluded groups, the situation will improve in the future and network access shall progressively be provided to all organisational participants.

More From This Category

Does Capital Structure Matter

The capital structure of a modern corporation is, at its rudimentary level, determined by the organisational need for long-term funds and its satisfaction through two specific long-term capital sources, i.e. shareholder-provided equity and long-term debt from diverse external agencies (Damodaran, 2004). These sources, with specific regard to joint stock companies, retain their identity but assume different shapes.

Ethical and Governance Challenges for Businesses and Professionals

It is the duty of business organisations to refrain from engaging in actions that are harmful to their various stakeholders, including the society and the environment and furthermore work purposefully towards benefiting them.

Cultural and Linguistic Challenges of Internationalisation

MNCs and even other firms with more restricted operations have responded to these opportunities by expanding their international business swiftly and substantially. It must however be recognised that attempts at international expansion have resulted in significant challenges for internationalising firms in areas of environmental management and cultural and linguistic diversity.

0 Comments