Management Techniques: The Corporate Leadership Guide

Introduction

The defining phenomenon of the 21st century with relation to business and economy is change. The emergence and spread of globalisation, along with enormous advances in technology, instantaneous communication, cheaper travel, economic liberalisation, the growth of knowledge based economy, and the emergence of production centres and huge markets in fast developing economies like China, India and Brazil, have not just radically altered the business environment, but also the ways of conducting business (Tabb, 2004). Whilst such developments have brought in enormous business opportunities for western business firms, they have also been instrumental in the creation of complex challenges for corporate managements (Tabb, 2004).

Developments in business and economics are closely accompanied with evolution of management theory and practice. A good amount of contemporary management thought and discussion concerns corporate leadership, (the subject of this study), the various challenges faced by modern day managements, and the duties and responsibilities of modern business leaders (Silzer, 2002).

Anglo-American businesses have traditionally placed their business leaders on exalted pedestals and chosen to revere them with the same intensity accorded to political, military and sporting heroes (Harding, 2003). Glorified by the media, written about by management authors and journalists, and feted by politicians, business leaders like Henry Ford in the past and Bill Gates and Richard Branson in current times have acquired larger than life personas and achieved superhero status (Harding, 2003). Such leaders are considered to be key individualist drivers of the fortunes of their organisations and felt to be far different from regular managers and executives in matters of vision, leadership, drive, and dynamism (Harding, 2003).

Whilst the cult of the superhero manager continues to thrive, contemporary management thought is bringing up with a number of new leadership models (Fletcher, 2002). One school of experts feels the concept of the superhero manager to be outdated and completely out of sync with the demands of the modern day networked knowledge based economy (Fletcher, 2002). Such management authorities feel that individualist “heroic” managers have little to contribute to contemporary business challenges and should give way to collaborative managers, who are networked with their environment and can meet multifarious challenges through mutual reinforcement, greater coordination and the harnessing of multidisciplinary resources (Fletcher, 2002).

Other experts like Greiner (Organizational Growth Cycles, 2009), and Colin Hales (1993) aver that the concept of the superhero manager is essentially fallacious because organisational growth is by and large accompanied by numerous organisational developments and the formation of various groups and sub-groups who strongly influence the actions and working of business firms . The concept of the superhero leader who single-handedly steers his organisation towards growth and wealth is anachronistic with such basic facts and is thus largely false.

This study attempts to examine and discuss these various lines of thought and obtain a holistic view on the different perceptions regarding leadership and organisational working.

The Manager as Individualist Leader and Superhero

Philip, king of Macedonia and father of Alexander is reputed to have stated that “an army of deer led by a lion is more to be feared than an army of lion led by a deer.” (Holt, 2003)

Philip’s perception of a leader is not very different from the traditional Anglo-American view of the archetypal business leader as the superhero, who single-handedly drives his organisation towards business success. Endowed with vision, courage, enterprise, honesty and perseverance such business leaders are felt to be far superior in their ability than regular managers and often assume larger than life personas that are comparable to national and military heroes like Patton or Montgomery. Time magazine, an otherwise pro-establishment and rather strait-laced publication writes of aviation tycoon Richard Branson thus;

“Richard Branson (once he is travelling in space) will be able to look down on the world and reflect on the mark he’s made on it. The entrepreneur built his Virgin brand into a renowned international business empire by packaging pleasure. His record label made bedfellows of the Sex Pistols and Genesis; his transatlantic airline sexed up a strait-laced industry. He possesses a Caribbean island and a thirst for adventure that has driven his record-breaking exploits in boats and balloons. TIME named (Branson) a champion of the environment. Branson is worried about the environment and he’s decided to clean it up. While he’s at it, he may just help save the planet.” (Mayer, 2007, P1)

Whilst such media genuflection by a responsible media publication for a man, whose airline is responsible for serious amounts of fossil fuel consumption and considerable global warming, is on the face of it rather strange, it is representative of the cult of the business superhero, which is constantly built up by flattering media articles, energetic public relations work and personality oriented books. Both the mainstream and SME literature is well populated by biographical and autobiographical books on business leaders (Harding, 2003). Successful business leaders like Iacocca and Jack Welch have written best sellers that combine business wisdom with self- glorification and perpetuate the tradition of the individualist superhero, who can mould a team of average executives into a world beating organisation (Harding, 2003).

FIGURE 1: THE BUSINESS LEADER AS SUPERHERO

Sociologists attribute such tendencies for glorification to Anglo-American cultural traits of high individualism; such leaders capture the public mind because of their appearance to be their own masters, sure of their supremacy and noticeably independent about issues like conventionality, conformist ways and means and the established rules for organisational accomplishment (Harding, 2003). This does suggest a rather strange paradox because headstrong individualism is not usually compatible with business success (Harding, 2003). Whilst individualism relates to a liberty of contemplation or action that is followed despite collective group objectives, business leadership concerns the pursuit of group interests and aims (Harding, 2003).

Business leadership in the UK and the United states is also closely associated with the concept of successful entrepreneurs (like Gates and Branson) who are perceived as solitary individuals pursuing opportunity with single-minded resoluteness.

“Entrepreneurship appears as a liberating philosophy of individual achievement. It is a doctrine which capitalises, quite literally, on individual effort. Embedded in the myth are whole ideologies of hard work, independence, thrift and a constellation of imputed ‘Victorian Values’. Since Samuel Smiles in 1859, and his Yankee cousin, Alger Hiss, evangelised self help as opportunity, the myth of the individual striving is maintained. Thus the entrepreneur enjoys a rare and heroic status, “men for whom the hazards are exhilaration”(Dodd, 2007, P3)

New Leadership and Management Models

Recent times have however seen the emergence of a number of models that challenge such concepts of leadership (Fletcher, 2002, P 1 to 4). Management experts state that whilst the concept of the manager as leader and individualist superhero has been widespread in SME and general business literature, such concepts are now being challenged and that opinion is building up not only on the need to discard such traditional stereotypes but to appreciate that business purposes are better served by shared leadership and collaborative business practices, which are widely distributed throughout organisations (Fletcher, 2002). Such approaches are best suited to change stolid, top-heavy organizations into supple, knowledge dominated organizations and make them better placed to meet the challenges of the information era and the globalised environment (Fletcher, 2002).

Leadership is now increasingly perceived as a joint social progression, a process that is increasingly becoming shared and dependent upon increasingly democratic interaction between senior and junior managers (Fletcher, 2002). It is also being progressively realised that business leaders might not have all the answers to business challenges or the appeal to get others to carry their plans and initiatives forward (Fletcher, 2002). Good leaders are on the other hand expected to construct environments that are conducive for shared learning and incessant improvement (Fletcher, 2002). The achievement of such knowledge oriented results depends not as much on charisma and power of personality as on emotional intelligence traits like empathy, listening, and self-awareness, as well as the capacity to build relationships with others, learn from them and give them power (Fletcher, 2002).

Whilst such leadership models, which speak of the need to change stereotypical leadership traits and attributes in order to be better equipped to face modern day challenges, are increasingly making themselves apparent in management literature, other thoughtful models are putting forward the case that the role of the leader as the individualist superhero may be essentially fallacious and that the growth and progress of organisations depend upon a number of other factors.

“Peggy McIntosh, for example, notes that while we may focus on leaders as heroes, they are but the tip of the iceberg. In reality, their ‘individual achievement’ is enabled by a vast network of collaboration and support. Wilfred Draft uses another, equally compelling image from the sea. He notes that while we might see the white caps in the water as leading, it is actually the deep blue sea that determines the direction and power of the ocean.” (Fletcher, 2002, P1).

Such models, which challenge the very concept of individual accomplishment and autonomous individuality, are contained in the writings of both Larry Greiner, the well known organisational development expert and management author Colin Hales.

Greiner makes the point that most organisations grow through five distinct and stable evolutionary stages that are punctuated by periods of unrest and disturbance, when such organisations shift from one phase to another (Organizational Growth Cycles, 2009). The first phase, which is essentially creative and concerned with the construction of the product and the building of the market, is dominated by the founding fathers of the company (Organizational Growth Cycles, 2009). This phase continues until the business environment is marred by tension between the fathers because of increased managerial responsibilities and is followed by the selection and installation of a chief executive who has the confidence of all the fathers (Organizational Growth Cycles, 2009). This time segment is characterised by the development of a senior management team who run the organisation, even as the junior managers function mostly as functional experts, and comes to an end only when junior managers become too restive and want a greater say in organisational affairs (Organizational Growth Cycles, 2009). This period, known as the phase of decentralisation is normally accompanied by work disruption and is followed by excessive centralisation and red tape-ism (Organizational Growth Cycles, 2009). Mature organisations grow out of this phase and adopt collaborative and spontaneous cultures that are based upon self-governance and individual restraint (Organizational Growth Cycles, 2009).

Whilst Greiner’s theory of development implies that the growth of organisations follow reasonably determined paths and the function of the leader is dominant only during the creative phase, Hales makes the point that the growth of organisations is accompanied by five phenomena, namely (a) specialisation of individual functions, (b) mechanisms for coordination and control, (c) formalisation of activity, (d) distinction between formal work arrangements and informal relationships, and (e) the acquisition by the organisation of a life of its own that is different from that of its participants (Hales, 1993).

Both Greiner and Hales, albeit in different ways, make the point that organisations grow, prosper or fail for a variety of reasons that are distinct from the quality of leadership or the personality of the leader, implying that the perception of a business leader as an individualist and highly driven superhero is implausible, to say the least, and should be rejected outright.

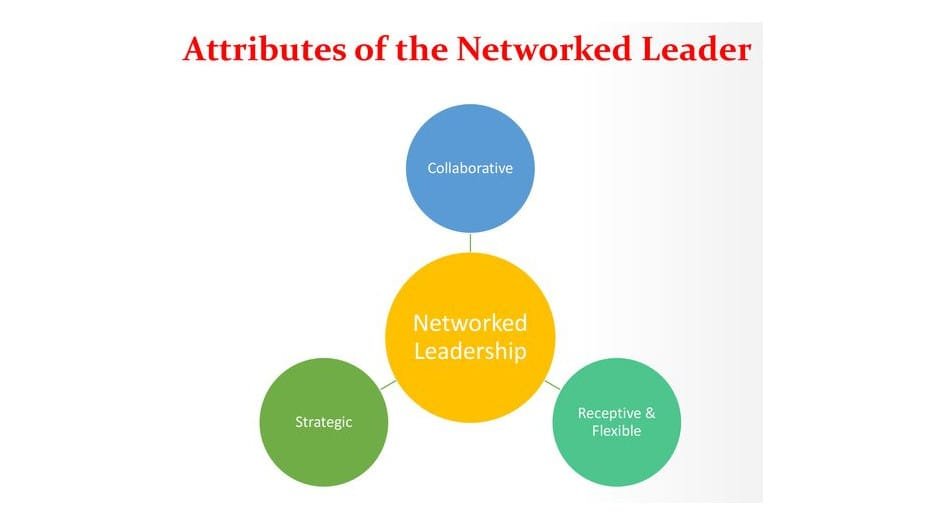

Figure 2: Networked Leadership

Such routes of growth lead to the evolution of a number of self-sustaining systems and networks handled by managers who use the available corporate resources to achieve their objectives.

Conclusions

The new models of corporate leadership, which are coming up in modern day management theory, are exceedingly critical of the traditional perception of the business leader as the all-conquering superhero.

The image of corporate leaders is taking a beating, not just because of the emergence of such theories, but also because of general disillusionment with the role of leaders in Enron like scams and the widespread avarice and disregard for responsibility on their part during the development of the current economic crisis.

On the flip side there still remain many who are convinced of the superior ability of people like Gates, Branson or Mittal and refuse to believe that corporations like Microsoft, Virgin or Arcelor Mittal could have come about without the personal attributes of their leaders.

The truth, as always lies somewhere in between these extremes and the cult of the superhero manager is far from over.

References

Dodd, D, (2007), “Mumpsimus and the Mything of the Individualistic Entrepreneur”, International Small Business Journal, 25 (4): 1-14.

Fletcher, J, (2002), “The Greatly Exaggerated Demise of Heroic Leadership: Gender, Power, and the Myth of the Female Advantage”, Center for gender in Organisations, Retrieved December 3, 2009 from www.simmons.edu/gsm/cgo

Hales, C, (1993), Managing through Organisation: The management process, forms of organisation, and the work of managers, London: Routledge.

Harding, N, (2003), The Social Construction of Management: Texts and Identities, New York: Routledge.

Holt, F. L, (2003), Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Mailick, S., & Stumpf, S. A, (1998), Learning Theory in the Practice of Management Development: Evolution and Applications, Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Mayer, C, (2007), “Heroes of the environment”, Time, Retrieved December 3, 2009 from www.time.com/time/specials/2007/0,28757,1663317,00.html

Organizational Growth Cycles, (2009), ACCEL, Retrieved December 3, 2009 from www.accel-team.com/techniques/orgGrowth.html

Silzer, R. (2002). The 21st Century Executive: Innovative Practices for Building Leadership at the Top. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tabb, W. K. (2004). Economic Governance in the Age of Globalization, New York: Columbia University Press.

More From This Category

Cultural and Linguistic Challenges of Internationalisation

MNCs and even other firms with more restricted operations have responded to these opportunities by expanding their international business swiftly and substantially. It must however be recognised that attempts at international expansion have resulted in significant challenges for internationalising firms in areas of environmental management and cultural and linguistic diversity.

Corporate Governance in the light of Agency and Other Theories

Heightened awareness about corporate governance has in recent years led to the emergence of a number of theories on corporate governance. Corporate governance theory commenced with the agency theory, grew into the stewardship and stakeholder theories, and evolved further into the resource dependency, transaction cost and political theories.

The Use of AI To Improve Leadership Development

AI is ideal for leadership development because of its utility in enhancement of diagnostic skills, complex simulation, number crunching, talent identification and leader selection.

0 Comments