Organisational Resilience: What is it and why does it matter during a Crisis

Introduction & Overview

This essay aims to engage in a critical discussion of the various aspects and implications of organisational resilience in the context of non-profit creative and cultural (NPCC) organisations.

Robinson (2010) described organisational resilience as the ability to continue in the face of changing times and economic circumstances, lost business, or staff, or to respond in natural or man-made disasters of one type or another. Recent years, in this context, have been difficult for most organisations (both in the profit and the not for profit sectors), in Europe and North America (Robinson, 2010). The development of the banking crisis in the USA, followed by the occurrence of a severe and sustained economic downturn across the western nations and other advanced economies, exposed the majority of organisations in these countries to severe economic and financial difficulties, resulting in lower incomes, poorer cash flows, economic losses and the need to downsize and terminate employees (Strycharczyk & Elvin, 2014). The severity and continuance of the economic crisis led to the closure of thousands of organisations and underlined the need for organisational resilience to survive difficult times (Strycharczyk & Elvin, 2014).

The overwhelming majority of organisations inevitably face, at one point of time or another, severe and difficult circumstances that threaten their very survival (Valikangas, 2010). Such circumstances can stem from various reasons, including economic recession, technological advances, loss of customers, shrinking of audiences, withdrawal of funding, or unanticipated disasters (Foord, 2008). The ability of organisations to withstand and survive such crises depends upon their organisational resilience, an attribute that differs from organisation to organisation and is built through the implementation of various strategies and policies in areas like organisational structure, human resource management, funding, reserve creation, innovative ability, operational leanness, and resource utilisation (McManus et al., 2007).

NPCC organisations work towards the furtherance of culture and creativity in various areas, especially the performing arts (Hannum et al., 2011). They have specific missions and whilst they earn surplus revenues, such surpluses are utilised for furtherance of organisational objectives and are not distributed in the form of profits to founders or shareholders (Hannum et al., 2011). It is important to note that NPCC organisations are significantly more vulnerable to adverse economic and other environmental circumstances than their counterparts in business on account of the not for profit orientation of their activities, their dearth of management skills, infrastructural resources and financial reserves, and their dependence upon external funding (Cherbo et al., 2008). Such organisations are amongst the first to be affected in times of economic difficulties or other calamities, with benefactors tightening their purse strings and audiences reducing their spending on cultural entertainment (Jaguzny, 2011). It is thus of utmost importance for the management of these organisations to develop internal resilience and the ability to withstand and survive different types of adversity (Jaguzny, 2011).

This essay engages in a critical analysis of various aspects of organisational resilience, with particular regard to their applicability to NPCC organisations, and develops recommendations on the ways in which such organisations can enhance their internal resilience and ability to withstand adversity in an effective manner.

Organisational Resilience

Organisational resilience is widely perceived to be the internal capacity of organisations to anticipate various types of disruptions, adapt to changing circumstances, and build lasting value (Bolton et al., 2011).

With diverse geopolitical, social and economic developments and continuous advancements in areas of technology constantly adding to global turbulence, instability and uncertainty have become elemental traits of the continuously changing contemporary environment (HKU, 2010). The overwhelming majority of contemporary organisations exist and operate in extremely challenging and dynamic environments, constantly facing increasing and unprecedented possibilities of disruptions to their existing environments and strategic plans (Suran, 2014). Organisational failure to anticipate such changes is becoming increasingly common and leading to severe losses and organisational closures in diverse sectors (HKU, 2010).

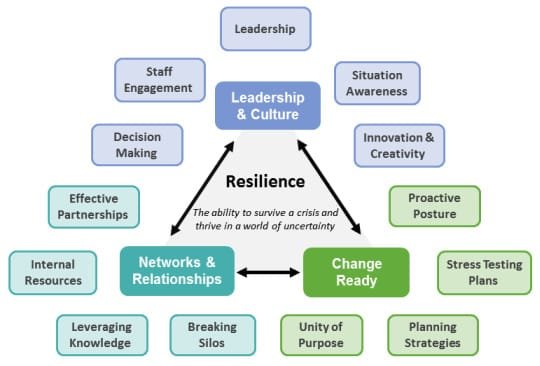

Management and organisational experts have stated that contemporary organisations must plan and make efforts to move beyond conventional governance and risk management models and focus on the development of organisational resilience (Suran, 2014). McManus et al., (2007) stated that enterprises with the ability to swiftly adjust to, or seize advantage from, unexpected environmental alterations, with minimal damage to their organisational missions and operations, can be termed to be resilient. The Resilient Organisations Research Programme (2013) identified 13 indicators of organisational resilience, which are depicted in the following diagram.

(Source: Resilient Organisations Research Programme, 2012, p 1)

The above diagram indicates 13 elements of organisational resilience, namely (1) leadership, (2) staff engagement, (3) situational awareness, (4) decision making authority, (5) creativity and innovation, (6) effective partnerships, (7) leveraging of knowledge, (8) breaking of silos, (9) internal resources, (10) unity of purpose, (11) proactive posture, (12) planning strategies and (13) stress testing plans (Resilient Organisations Research Programme, 2012).

The following table provides details about how each of these elements and contribute to the development of organisational resilience.

Table 1: Indicators of Resilience

Indicators of Resilience | Details |

Leadership | Strong crisis leadership in an organisation helps in ensuring effective decision making and good management during times of difficulty, thereby helping organisations to perform effectively under stress. |

Staff Engagement | High levels of engagement and involvement of staff results in greater appreciation amongst employees about the relationship between their own work, organisational resilience and long term organisational success. Empowerment of staff results in greater employee ability in resolving problems. |

Situational Awareness | The enhancement of employee awareness about the organisation, its challenges and its problems results in enhancement of organisational resilience. The eagerness and desire amongst employees for sharing good and bad news about organisational issues results in the development of early warning signals and the possibility of quick organisational responses to environmental difficulties. |

Decision Making | Empowerment of employees, with regard to decision making authority on their work, facilitates swift crisis response. The involvement of highly skilled staff members in organisational decision making helps in the enhancement of the quality of organisational decisions during periods of crisis. |

Innovation and Creativity | The fostering of organisational innovation and creativity through the adoption of diverse strategies and policies facilitates generation of unorthodox and effective solutions in times of crisis. |

Effective Partnerships | The development of effective and long-lasting partnerships with suppliers, financiers, and other stakeholders helps in accessing of external resources during difficult times, thereby enhancing organisational ability to deal with critical situations. |

Leveraging of Knowledge | The development of a learning organisation through the sharing of explicit knowledge and the institutionalisation of tacit knowledge helps organisations to draw upon strong knowledge bases, evaluate and analyse the various elements of the organisational environment in times of difficulty, and formulate and adopt effective responses. |

Breaking of Silos | The minimisation of divisive organisational barriers, cultural, social and behavioural, through the enhancement of organisational communication and transparency helps in the generation of greater organisational commitment and unity in responses during times of crisis. |

Internal Resources | Organisational ability to effectively mobilise and marshal various resources during difficult times helps organisations in coping more effectively with environmental difficulties and changes on a sustained basis. |

Unity of Purpose | Organisational clarity on priorities and unity of purpose in the aftermath of a crisis helps in achievement of consistency in the formulation and implementation of organisational responses. |

Proactive Posture | The readiness of managements to respond, both strategically and behaviourally, to early warning signals about changes in their internal and external environments facilitates the adoption of quick responses and prevents the escalation of crises. |

Planning Strategies | Organisational ability to develop and evaluate diverse plans and strategies for the management of vulnerabilities concerning the organisational environment and its stakeholders can help considerably in the management of environmental difficulties. |

Stress Testing Plans | The involvement and participation of employees in various simulation exercises has been seen to help organisations significantly in the management of crises. |

(Source: Resilient Organisations Research Programme, 2012; Jaguzny, 2011; Valikangas, 2010)

There is wide agreement on the importance of organisational resilience in the increasingly predictable and volatile environment and the organisational consequences of external events (Walker & Salt, 2008). Contemporary organisations operate in environments of constant change and have to additionally cope with organisational employees who are (1) less steady in their career decisions than their predecessors and(2) engaged in faster career transitions (Walker & Salt, 2008).

Foord (2008) stated that resilient organisations prepare for the best, as also for the worst, and nurture and encourage organisational learning. The coming together of personal talent with a balanced approach towards management of explicit and tacit knowledge in a productive environment enhanced their learning and equipped them to face disasters with resoluteness, recover from trauma and restore operational capabilities (Robinson, 2010). Individuals in such organisations were aware of the possibility of failure and constantly searched for mechanisms to enhance operational reliability (Robinson, 2010).

Folke et al., (2002) stated that the key to the development of organisational resilience stemmed from making the organisational capability to adapt and recover second nature to institutional working. Organisations that succeeded in doing so became self organising, dynamic and capable of responding to various environmental changes (Folke et al., 2002). Walker & Salt (2008) stated that such resilience could be enhanced by the designing of resilient systems that are focussed upon decentralisation and comprise independent subsystems that engage in interactive information exchange.

Characteristics of NPCC Organisations

NPCC organisations work towards the furtherance of culture and creativity in diverse ways (Caves, 2000). They furthermore invest their complete surpluses towards the achievement of their objectives and do not retain or distribute them in the form of profits (Braun & Lavanga, 2007). These organisations have some specific characteristics, which not only differentiate them in several ways from their counterparts in the business sector, but also enhance their vulnerability to environmental changes and adversely affect their organisational resilience (Caves, 2000).

The overwhelming majority of such organisations are micro and small enterprises, with employees numbering less than ten (Hartley, 2008). Whilst the smaller of such enterprises are managed and controlled solely by their founders, the larger of them often have two competing centres of command, namely the person in charge of the creative side, called the Arts Director and the manager in charge of operations, termed the Executive Director (Braun & Lavanga, 2007). Such organisations more often than not have bifurcated organisational structures, characterised by tensions between the creative and executive divisions; such tensions primarily stem on account of differences in their approach towards the utilisation of organisational resources, generation of revenues and operational expenditure (Hartley, 2008).

The majority of such organisations are unable to provide good and sustained levels of remuneration to their members and often depend upon volunteers, freelancers and part-timers for the conduct of organisational operations, both in the creative and the executive segments of their institutions (Caves, 2000). High levels of transience amongst the employees of such organisations result in significant inadequacies in the development of organisational structures, strategies and policies, and methods of doing work (Braun & Lavanga, 2007). This in turn results in inadequacies in the institutionalisation and management of explicit and tacit knowledge and renders these organisations far more vulnerable in terms of coping with environmental alterations (Bolton et al., 2011).

The activities of such organisations are often ad-hoc in nature and suffer from lack of serious planning (Hennessey & Amabile, 2009). Various research studies on the NPCC sector have revealed that such organisations often lack in areas of management leadership, experience and expertise (Hennessey & Amabile, 2009). Whilst these organisations are founded and driven by people with vision and mission and often have laudable strategic objectives and goals in areas of cultural and creative activity, the absence of high levels of management skills and expertise hinders the achievement of such missions, goals and objectives (Bolton et al., 2011). Such inadequacies very frequently result in a lack of attention to diverse important operational and financial areas and in the development of a range of avoidable financial and operational challenges and difficulties (Foord, 2008).

Many of these organisations, research has revealed, suffer from inadequate financial planning over the medium and long term and are characterised by the organisational propensity for matching revenues with expenses on a short term basis (Caves, 2000). Such tendencies and attitudes result in the development of inadequate financial reserves and in the reduction of their attractiveness to bankers and lending institutions (Hennessey & Amabile, 2009). Banks and lending institutions consequently often exhibit apprehensions and hesitations in providing funds to the NPCC sector, which in turn leads to scarcity of financial resources and lack of organisational ability to (a) attract high quality talent, (b) invest in required infrastructure and (c) spend in areas of marketing and operations by NPCC organisations (Bolton et al., 2011).

It is also important to note that the market for cultural goods is volatile and unpredictable, and organisations have to adopt operational strategies that are often based on intuitive and emotional knowledge (Hennessey & Amabile, 2009). Consumers are often unaware of their tastes in cultural markets and discover them through repeated experiences in sequential processes of learning through consumption (Cherbo et al., 2008). The management of such organisations often have to struggle to anticipate market value, which in turn results in difficulties in attraction of funding (Cherbo et al., 2008). It also needs to be noted that many NPCC organisations are dependent upon external funding through donations and grants for many of their activities, a feature that makes them especially vulnerable to reduction of financial resources in times of economic difficulties and downturn (Caves, 2000).

Bolton (2011) stated that many not for profit arts and cultural organisations still functioned on the model of matching and balancing income with expenditure. They lacked sufficient reserves for coping with difficult times and designated monies for organisational investments and for bringing about required organisational change and evolution (Cherbo et al., 2008). Such organisations needed funds, for instance, to develop fresh websites and systems for the collection of more information about their audiences and for better communication with them (Cherbo et al., 2008).

Challenges for NPCC Organisations

Cultural and creative organisations in the not for profit sector must contend with swiftly changing environmental conditions and a multitude of challenges in contemporary times (Pollack et al., 2004). Such organisations operate in environments of uncertainty (Pollack et al., 2004). Many of them work under severe financial strain, regardless of the economic climate, on account of increasing financial pressures and growing gaps between income and expenditure (Pollack et al., 2004). Several of them depend upon governmental subsidies or are forced to increase their ticket prices in order to balance their financial deficits (Zappala & Lyons, 2008). Both these measures do not provide for consistent revenues and can result in several types of marketing problems (Zappala & Lyons, 2008). Whilst governments can change their policies regarding financial support, increasing the prices of tickets can make performances too expensive for many people (Zappala & Lyons, 2008). With funding for cultural and creative organisations being seen to be dispensable by many corporate organisations, they are often at the mercy of the economy and are the first to feel the pressure when budget cuts are made by supporters of arts (Higgs & Cunningham, 2009).

Such organisations can also be adversely affected by political decisions that aim to reduce governmental funding (Higgs & Cunningham, 2009). With support for cultural and creative activities fluctuating between political parties, it has become difficult to establish a consistent position on the issue (Strycharczyk & Elvin, 2014).

NPCC organisations also have to contend with competition for resources like audience members, leisure time, education and technology (Zappala & Lyons, 2008). With the field currently lacking managers and leaders trained in administration and management, many such organisations are unable to respond effectively to increasing competition from other cultural and creative options that are being offered through media like television and the Internet (Strycharczyk & Elvin, 2014).

Technological advancements can also result in the development of significant challenges for NPCC organisations (Zappala & Lyons, 2008). Technology can strongly influence audience participation and impact organisational effectiveness (Higgs & Cunningham, 2009). It can assist organisations in managing scarce resources, expanding strategic goals and in cutting overhead costs (Pollack et al., 2004). Many organisations in this sector however still have very limited technical expertise and remain unaware of the diverse options and tools available to them (Pollack et al., 2004).

Resistance to change, more specifically in technological areas, is endemic in the NPCC sector and there seems to be a dearth of leadership support that can bring about attitudinal changes (Pollack et al., 2004). There is little doubt of the diverse and complex challenges faced by NPCC organisations and concern has been growing about the ability of organisational management in this sector to respond effectively to environmental changes (Higgs & Cunningham, 2009).

Development of Organisational Resilience

The study carried out for the purpose of this essay revealed that the majority of NPCC organisations focused on operational models that were deficient from the perspectives of long term growth, financial stability, learning management and harnessing of technology (Valikangas, 2010). Such inadequacies made these organisations increasingly vulnerable to environmental change, economic fluctuations and technological advancements (Strycharczyk & Elvin, 2014).

The leaderships of NPCC organisations should pay far greater attention to the development of viable business models, based upon long term planning, institutionalisation of learning and utilisation of technology (Strycharczyk & Elvin, 2014). Whilst many of such organisations may have to continue to work with volunteers, part-timers and temporary staff, the institutionalisation of effective methods for revenue generation, cost control, planning and creation of financial reserves can go a long way in the development of organisational resilience (Walker & Salt, 2008).

The leaderships of these organisations must also shed their apprehensions about an aversion to technological advancement and embrace the Internet and the electronic medium, both for optimisation of operation and for augmentation of revenues (McManus et al., 2007). The Internet and Web2.0 offer diverse options to contemporary organisations to leverage their resources and optimise their activities (Valikangas, 2010). It is essential for NPCC organisations to embrace technology if they wish to survive and prosper in an Internet dominated environment (Valikangas, 2010). The management of these organisations should adopt specific measures to remedy their long tradition of instability and engage in proactive methods for generation of organisational resilience, rather than in reacting erratically to the demands of the ever-changing contemporary environment (Suran, 2014).

Conclusions and Recommendations

This essay aimed to engage in a critical discussion of organisational resilience, with particular regard to its implications for not for profit cultural and creative organisations.

The conduct of the study revealed that modern organisations, if they have to be successful, must plan for changing environmental conditions and develop organisational resilience to counter and overcome them. Organisational management must move beyond conventional risk management approaches and adopt holistic measures involving all organisational employees, departments, and functions in order to make them ready to anticipate and pre-empt change.

The study furthermore revealed that NPCC organisations are particularly vulnerable to adverse environmental changes because of diverse inadequacies in areas of financial, operational, technology and change management. The leaderships of such organisations must move beyond their conventional attitudes towards organisational management and take a range of steps for enhancement of organisational resilience if they wish to survive and prosper in the challenging contemporary environment.

References

Braun, E., & Lavanga, M., 2007, An International Comparative Quick Scan of National Policies for Creative Industries, Rotterdam: WURICUR, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Caves, R., 2000, Creative Industries: Contracts between Art and Commerce, Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press

Carbo, J.M., Vogel, H.L., & Wyszomirski, M.J., 2008, “Toward an Arts and Creative Sector”, In J. M. Cherbo, R. A. Stewart, & M. J. Wyszomirski (Eds.), Understanding the arts and creative sector in the United States, New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S., Elmqvist, T., Gunderson, L., & Holling, C., 2002, “Resilience and sustainable development: building adaptive capacity in a world of transformations”, AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, Vol. 31, No. 5: pp. 437–440.

Foord, J., 2008, “Strategies for creative industries: an international review”, Creative Industries Journal, Vol.1, No. (2): pp. 91–114.

Hannum, K.M., Deal, J., Howard, l.L., Lu, L., Ruderman, M.N., Stawiski, S., Zane, N., & Price, R., 2011, Emerging Leadership in Non-profit Organisations: Myths, Meaning, and Motivations, Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

Hartley, J., 2008, “From the Consciousness Industry to Creative Industries: Consumer created content, social network markets and the growth of knowledge”, in Holt, J. and Perren, A. (eds), Media Industries: History, Theory and Methods, Oxford: Blackwell.

Hennessey, B. A., & Amabile, T.M., 2009, “Creativity”, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 61: pp. 569 – 598.

Higgs, P., & Cunningham, S., 2009, “Creative Industries Mapping: Where have we come from and where are we going?”, in Creative Industries Journal, Vol.1, No. (1): pp. 7-30.

HKU, 2010, The Entrepreneurial Dimension of the Cultural and Creative Industries, Utrecht: Hogeschool vor de Kunsten Utrecht.

January, L., 2011, “The resilient non-profit: key elements for the non-profit”, Available at: http://www.campionfoundation.org/downloads/report-resilient-nonprofit.pdf (accessed December 24, 2014).

McManus, S., Seville, E., Brunsdon, D., & Vargo, J., 2007, “Resilience Management: A framework for assessing and improving the resilience of organisations”, Resilient Organisations Programme, Available at: www.resorgs.org.nz (accessed December 24, 2014).

Pollack, T., Rooney, P., & Wing, K., 2004, “Toward a Theory of Organizational Fragility in the Nonprofit Sector”, paper presented at 2004 International Conference on Systems Thinking in Management, Indiana University: Indianapolis.

Resilient Organisations Research Programme, 2012, “What is Organisational Resilience”, Available at: http://www.resorgs.org.nz/Content/what-is-organisational-resilience.html (accessed December 24, 2014).

Robinson, M., 2010, “Making adaptive resilience real”, Available at: http://www.artscouncil.org.uk/media/uploads/making_adaptive_resilience_real.pdf (accessed December 24, 2014).

Strycharczyk, D., & Elvin, C., 2014, Developing Resilient Organisations: How to Create an Adaptive, High-Performance and Engaged Organization, 1st edition, London: Kogan Page.

Suran, S.A., 2014, The DNA of the Resilient Organisation – How One Collective Heartbeat Creates Continuous Competitive Advantage, 1st edition, London: Stargazer Pub Co.

Valikangas, L., 2010, The Resilient Organization: How Adaptive Cultures Thrive Even When Strategy Fails, 1st edition, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Walker, B., & Salt, D., 2008, Resilience Thinking: Sustaining ecosystems and people in a changing world, NY: Island Press.

Zappala, G., & Lyons, M., 2008, “Not-for-profit organisations and business: mapping the extent and scope of community-business partnership in Australia”, in Barraket, J (ed) Strategic Issues for the Not-For-Profit Sector, Sydney: UNSW Press.

More From This Category

Globalisation Challenges

Globalisation is the tendency of the public and economies to move towards greater economic, cultural, political, and technological interdependence. It is a phenomenon that is characterised by denationalisation, (the lessening of relevance of national boundaries) and is different from internationalisation, (entities cooperating across national boundaries). The greater interdependence caused by globalisation is resulting in an increasingly freer flow of goods, services, money, people, and ideas across national borders.

Does Capital Structure Matter

The capital structure of a modern corporation is, at its rudimentary level, determined by the organisational need for long-term funds and its satisfaction through two specific long-term capital sources, i.e. shareholder-provided equity and long-term debt from diverse external agencies (Damodaran, 2004). These sources, with specific regard to joint stock companies, retain their identity but assume different shapes.

Ethical and Governance Challenges for Businesses and Professionals

It is the duty of business organisations to refrain from engaging in actions that are harmful to their various stakeholders, including the society and the environment and furthermore work purposefully towards benefiting them.

0 Comments