Consumer Behaviour and the Spa Industry

Published in 2021

Introduction

Modern day spas, commercial establishments that provide a range of services for improvement of physical and emotional well being, beautifying and nourishing human bodies and healing, and sustaining minds and spirits, constitute a rapidly growing sector of business and trade activity (Register, 2009).

Whilst the popularity of spas in modern times is a recent phenomenon, the origin of such establishments can be traced back to Greek and Roman times (Register, 2009). The Greeks patronised fragrant, warm and controlled temperature baths as early as 500 BC. Again spacious and splendid baths were built across the Roman Empire during its heyday for the comfort and relaxation of its citizens (Register, 2009). Such private and public conveniences offered baths with water of controlled fragrance and temperature, a range of massages and different skin improvement treatments (Register, 2009). The era of the renaissance in Europe is associated with the use of healing springs and saunas (Register, 2009). The modern day use of the term spa comes from the town of the same name in Europe, which came to be known for the healing quality of its natural springs (Register, 2009).

Figure 1: An Illustration of a Roman Spa

Whilst much of available literature associates such facilities with western civilization, the emperors, kings and queens of eastern nations like China and India are also known to have regularly enjoyed the pleasures of bathing in water made sensuous by the addition of various aromatic oils, milk, and petals of fragrant flowers.

Spas are making an enormous revival in contemporary times (Register, 2009). Their numbers are growing rapidly across the world, and spas are mushrooming in the cities of North America, Europe and Asia (Register, 2009). Whilst concentrated in affluent cities, they are also to be found in practically every tourist destination (Register, 2009). The growth in the spa industry is also leading to a surge in the range of offered services, which now include a wide range of treatments and offerings, both modern and traditional, originating from the West and the East, to satisfy the different needs of their ever growing clientele (Register, 2009). Apart from simple baths and Jacuzzis spa services also include various types of mud packs, massages, facials, hair styling, manicure and pedicure, aroma therapy, acupuncture, all forming part of a perpetually increasing range of services that aim to pleasure bodies and minds (Register, 2009).

Modern day behavioural experts feel the contemporary interest in spas to be an outcome of the wave of hedonism that is spreading through western society (Foxall, 2009, P 27 to 43). Representing the pursuit of pleasure by humans, hedonism has in the past been associated with times of prosperity, affluence and increase in artistic and creative pursuits (Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000, P 60 to 71).

The expenditure incurred by consumers at spas is not only very substantial, but is also felt by many people, especially from older age groups to be wasteful, irrational and not leading to any concrete or long term benefits (Foxall, 2009, P 27 to 43).

The spa industry on the other hand believes strongly in the worth of its service and is working strongly at converting changing consumer attitudes and behaviours into customer visits and sales (Register, 2009).

This study attempts to investigate and analyse consumer behaviour toward the spa industry, with special regard to its rationality, and the implications of such behaviour for marketing professionals.

Research and Discussion

Growth of Spas and Hedonism in Spa Customers

Spas continue to grow worldwide, even during the ongoing recession, the worst faced by the world since the depression of the 1930s (Register, 2009). The United States, in many ways the epicentre of the pleasure society, has nearly 15,000 spas (Register, 2009). Such establishments continue to grow rapidly across the world, in the U.K, in the metropolises of Europe, in Asian cities like Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Dubai, at beach resorts like Bali and Goa, and in exotic hideaways in the Himalayas (Register, 2009). Approximately 32 million people in the United States visit spas regularly, the majority of whom are women. In the U.K spas continue to open even as other business face difficult times (Register, 2009).

Hedonism, a Greek term that is associated with the pursuit of pleasure, is becoming a representative trait of contemporary society, especially so in advanced and affluent nations (Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000, P 60 to 71). An outcome of various factors like increased discretionary incomes, fewer family responsibilities (because of reasons like the breakdown of joint families, greater numbers of divorcees, and lower birth rates), lesser week days, shorter working hours, cheaper travel costs, and the opening up of numerous new pleasure pursuits, hedonism represents the contemporary attitudes of citizens of affluent societies to devote time, effort and money to the pursuit of pleasure (Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000, P 60 to 71). Hedonic attitudes often sway buying decisions of consumers away from their actual utilitarian needs and encourage people to take decisions that are associated more with pleasure than with practicality (Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000, P 60 to 71). A decision by a prospective house owner to buy an apartment, more for the view from the bedroom window, rather than for of the distance of the house from his place of work, provides an example of a hedonic, and some would say irrational, decision (Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000, P 60 to 71). Similarly people are often motivated to go to a spa and hand themselves over to masseurs and stylists for a period of luxurious indulgence when a visit to a hairdresser would have served their need to appear well groomed adequately.

Figure 2: Hedonism in Spa Customers

Whilst such behaviour can, by utilitarian yardsticks, be considered to be irrational, (Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000, P 60 to 71) most spa-goers engage in such activity and spend their money only after due thought. Such behavioural attitudes and anachronisms are now being analysed by marketing and behavioural experts intensively in order to meet consumer needs and drive business in the modern day consumer society (Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000, P 60 to 71).

Consumers and Rational Behaviour

The increasing tendency of consumers to visit spas is indicative of changing customer attitudes and behaviour (Blattberg, 2004, 32 to 37). Contemporary society has undergone dramatic transformation in the last few decades, particularly in its shift from being driven by producers to being totally dominated by consumers (Blattberg, 2004, 32 to 37).

Whilst business firms even a few decades back used to focus mainly on production and assumed that whatever was produced would be sold, they are now experiencing a dramatic environmental change that is seeing consumers dictating their preferences and enforcing their wants on suppliers of goods and services (Blattberg, 2004, 32 to 37). Consumer behaviour is now been intensely studied and analysed because consumers cannot be taken for granted by producers any more and play major and decisive roles in the success or failure of products and services (Blattberg, 2004, 32 to 37). Recent studies have shown that out of 11,000 new products that were introduced by 77 major companies, only 56% were present five years down the line (Consumer behaviour, 2009). Again the major mistakes in assessing consumer behaviour are seen to be made by successful companies who remain steeped in their smugness and complacency, refusing to accept the changes in consumer behaviour and perception that are occurring all around them (Consumer behaviour, 2009).

The study of consumer behaviour is based on concepts drawn from psychology, sociology, anthropology, marketing and economics (Foxall, 2009, P 72 to 108). All managers, it is widely accepted, need to understand and analyse consumer motivation and behaviour in order to market their products efficiently and effectively (Foxall, 2009, P 72 to 108).

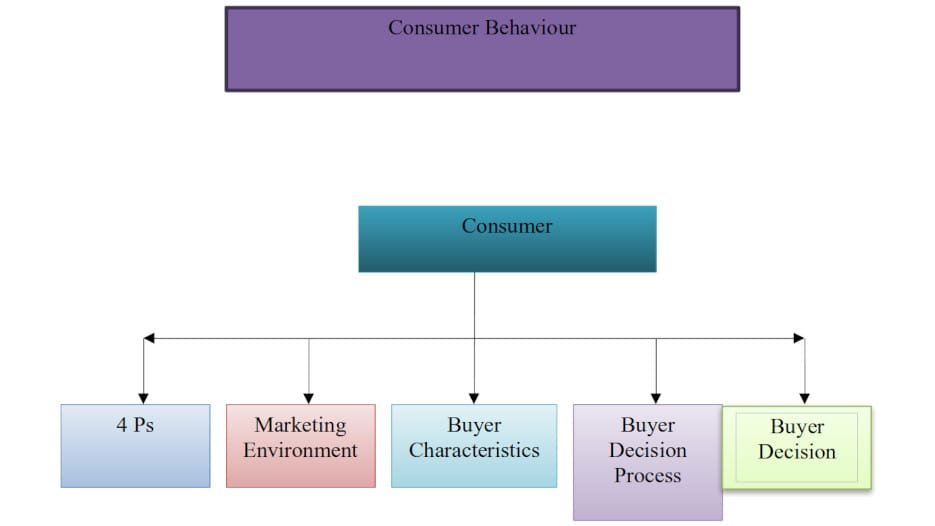

Phillip Kotler, in his widely known theory of consumer behaviour, states that consumer behaviour is influenced by a large number of factors that include marketing stimuli (namely the four Ps, product, price, place and promotion), the marketing environment, buyer characteristics and the consumer decision making process. The model provided below details the various forces that determine consumer behaviour (Foxall, 2009, P 74).

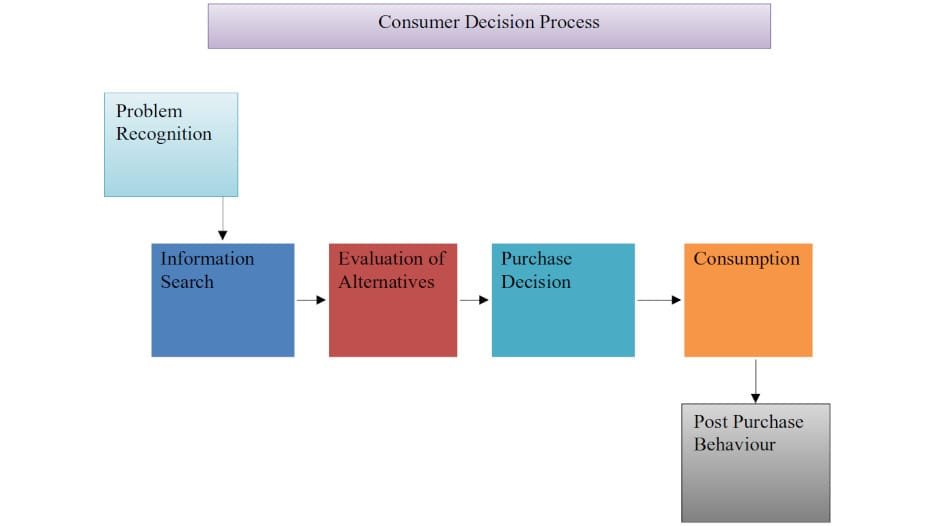

The marketing environment consists of political, cultural, technological and economic factors, whereas buyer characteristics are influenced by cultural, social, personal and psychological issues (Foxall, 2009, P 72 to 108). The consumer decision process (CDP) is on the other hand a complex course of action that comprises of many phases; it starts with the recognition of the need for a product or service, which then is followed by search for information, evaluation of alternatives, decision to buy, consumption of purchased product or service, and finally post consumption behaviour (Foxall, 2009, P 72 to 108).

The model of the Consumer Decision Process is illustrated below (Consumer behaviour, 2009):

The elaborateness of the consumer decision process should normally lead marketers to believe that such a complex process would on most occasions be rational and aim to provide the maximum utilitarian benefit to a consumer (Foxall, 2009, P 72 to 108). A person buying a house would, in line with such a process, decide upon a specific budget, and examine factors like proximity to place of work, nearness to schools, availability of required rooms, the size of the kitchen and similar other factors. In actual life such a decision is often swayed by seemingly irrational reasons like the view from the balcony, the colour of the flooring, or the accompanying membership to a golf club. A person buying a car is often influenced by factors like colour, design, fast acceleration, and internal luxuries into paying a higher price than what would be required for buying a standard vehicle with reliable features and low fuel consumption. A person needing just a shave and a haircut could similarly take a decision to give his hairdresser a miss, go to a spa and additionally enjoy a manicure, a pedicure, a facial and a body massage.

Whilst such behaviours are becoming increasingly common in the modern day environment of greater choice, greater income and more spare time, they tend to be termed as irrational decisions because they are not in consonance with satisfaction of utilitarian needs (O’Cass & McEwen, 2004, P 25 to 39). Behavioural experts however feel that consumer behaviour need not always be rational, and in fact often tends to be irrational (O’Cass & McEwen, 2004, P 25 to 39). They furthermore attribute such irrationality to a combination of a range of social, cultural and physiological factors that act in tandem and shape consumer reactions, behaviours and decisions (O’Cass & McEwen, 2004, P 25 to 39).

Sociology, Psychology and Consumer Behaviour

Social, psychological and cultural influences play very important roles in the consumer decision making process (Bagozzi & Dholakia, 1999, P 19 to 32). Social influences, which are also invariably related to cultural issues, refer to the pressures that people experience because of their affiliation or belonging to specific social segments (Bagozzi & Dholakia, 1999, P 19 to 32). Whilst such social segments are broadly defined by income, education, and ethnic identity, they are also influenced by factors like culture, language, religion, sex, and age. Social sub-groups like schools, colleges, local communities, social networking sites, personal friends and work acquaintances also play important roles in influencing consumer behaviour and buying decisions (Foxall, 2009, P 72 to 108). Personal factors include traits like friendliness, self confidence, introversion, extroversion, aggression and competition (Foxall, 2009, P 72 to 108). Psychological factors include issues like motivation, perception, learning, beliefs and attitude (Foxall, 2009, P 72 to 108).

Considering that beliefs and attitudes are also largely shaped by social and cultural influences, there exist a large number of interrelated forces that influence and affect consumer behaviour (Blattberg, 2004, 32 to 37). Whilst consumer behaviour is of course influenced by actual utilitarian needs and available income, which in normal circumstances should lead to rational or sensible decisions, it is also greatly influenced by an extensive range of social, cultural, psychological and personal issues (Blattberg, 2004, 32 to 37). Consumer buying decisions, in the overwhelming majority of cases are thus outcomes of a mix of numerous factors like actual needs, perceived needs, available income, available choices, and the many other intangible influencers of individual behaviour (Blattberg, 2004, 32 to 37).

Customer behaviour, as elaborated in the immediately preceding discussion, is shaped by a mix of rational and irrational factors, and it would be wrong to assume that decision making is either solely rational or irrational. Psychologists however do feel that the element of irrational behaviour increases with availability of income (Blattberg, 2004, 32 to 37). Individuals who do not have money in excess of that required for meeting their utilitarian needs have little scope to indulge their irrational desires (Blattberg, 2004, 32 to 37). Increased availability of money, time and choices on the other hand obviously spur people to engage in acts that would have otherwise not been possible (Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000, P 60 to 71). The pursuit of pleasure or hedonic behaviour springs primarily from increased incomes and greater choices of pleasure giving activities (Dhar & Wertenbroch, 2000, P 60 to 71).

A recent survey in the USA indicates that the largest percentage of spa-goers tend to come from the higher income groups (Spa Sentiment …, 2009). Postmodernists believe such behavioural traits to be representative of the modern society of conspicuous consumption that is fuelled by competitiveness, individual ego, social one-upmanship, reduced family responsibility and the pursuit of individual pleasure (Firat, 1991, P18).

Spas offer a range of physically and mentally satisfying services, which fall within the available discretionary incomes of citizens of affluent society and fuel hedonic activity.

Marketing of Spa Services

Modern spas focus primarily on providing pleasure to their customers. Whilst their services are described in effusive marketing copy as beneficial for both the body and the mind, their basic offering is that of pleasure, luxury and self-indulgence. As discussed earlier the contemporary societies of advanced nations are characterised by greater incomes, lesser responsibilities, more time, and an ever increasing range of choices in all areas of lifestyle, be they related to food, accommodation, cars, bathroom facilities, entertainment, holidays, personal grooming or emotional and mental fulfilment. Enormous improvements in communication technology have led to the emergence of numerous media channels, both physical and online, which are constantly mined to provide information about the range of available products and services, as well as their comparative merits and demerits.

Modern day marketing research, empowered by such advanced communication channels, constantly interact with consumers, investigate their likes and dislikes, and provide information to providers of goods and services, in order to continuously enlarge the range of choices and benefits available to customers (O’Cass & McEwen, 2004, P 25 to 39). The modern day consumption society is thus constantly provided with a range of choices in areas of goods and services that are in consonance with or aim to further contemporary consumption oriented lifestyles (O’Cass & McEwen, 2004, P 25 to 39).

Whilst spas were originally little more than sophisticated grooming establishments that through in Jacuzzis and massages, along with hair cuts, manicure and pedicures for their customers, they have progressively enlarged their range of services to include solutions for improving fitness, managing stress, increasing peace of mind and providing bodily pleasure, through a range of conventional and unconventional services; such services now include personal trainers, hypnotherapy, Tai Chi and time and rhythm cycles and are increasing every day (Register, 2009).

The desires for such services across social segments have led to tremendous market segmentation and spas now cater to people with average incomes to the super rates (Spa Sentiment …, 2009). The U.K for example has any number of standalone day spas that offer a range of specified services (Register, 2009). Many hotels have in-house spas that are more expensive and service clients who desire greater exclusivity and more uncommon luxuries. Ultra luxurious spas in the mountains and at expensive sea resorts provide services for the very rich and represent the last word in luxury (Register, 2009).

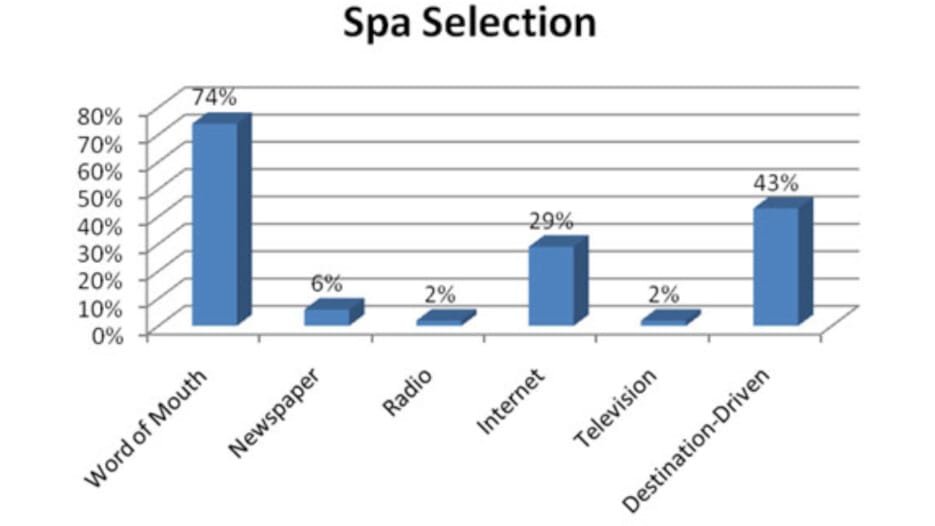

A recent survey by Coyle Hospitality Group and WTS International indicates that consumers of spas come from all age groups and select spas for a range of reasons (Spa Sentiment …, 2009). The chart provided below indicates the ranking of consumer preferences in spa selection.

Spa Sentiment, 2009

The table provided below also provides important information about the preferences of spa-goers (Spa Sentiment, 2009).

Spas are selected mostly on the basis of word of mouth and people tend to go to spas near their homes, when they are not travelling out of their cities and towns. The most favoured treatments are massages, even as exotic treatments like hydro-therapy and laser are used by as much as 10% of spa goers. The important reasons that encourage people to visit spas are relaxation, stress management, health and beauty. Increasing self esteem and confidence, along with reducing ageing, are also important motivators.

The most important attributes that people look for in spas are cleanliness, professional staff, pleasant atmosphere and complementary refreshments.

Whilst price is a very important factor in decision making, most decisions are based on a mix of the elaborated considerations.

Such information reveal that whilst consumers crave for luxury and indulgence, their selection of service providers is influenced by issues like price, cleanliness and quality of staff. It thus becomes evident that both rational and irrational forces play important roles in the consumer decision process. Whilst the need for the spa service could be perceived as irrational (and possibly fits only very awkwardly into Maslow’s “status” needs), the actual search and selection process is driven by rational factors like proximity, price, cleanliness and professional ability.

Conclusion

Several modern experts have researched and studied at length on continuous organisational failures in control of employee behaviour despite the availability of numerous models and theories, which explain the reasons behind employee behaviour and the steps that can be taken to control and shape such behaviour with effectiveness and efficiency (King & Lawley, 2019). Holmes (2012) stated that failure to control employee behaviour can stem from several reasons like (1) inadequate resources, in terms of money, supplies and organisational infrastructure to complete tasks, (2) different types of obstacles like for example collaboration with other departments or swift decisions by seniors that are necessary for task completion, (3) unclear or exaggerated expectations, (4) absence of skills necessary for completing tasks, (5) inadequate rewards or praise for good work, (6) absence of penalties for poor performance and (7) employee burnout on account of excessive organisational pressure.

Manzoni and Barsoux (1998), in an article for the Harvard Business Review stated that managers typically do not blame themselves for employees who perform poorly or do not function as they are instructed. They often give various reasons for employee failure including lack of job understanding, inadequate knowledge and skills or an inherent desire for shirking work. Gerwing (2016) stated from his research on employee behaviour in various organisations that employee behaviour is adversely affected because of high levels of micro management, including excessive paper work requirements, need for approval for small decisions and high levels of supervision. Employees often interpret high levels of supervision as lack of trust with their abilities, which, in turn undermines their confidence as well as their desire to put in additional effort (Hill et al., 2012).

Manzoni and Barsoux (1998) provide a real life example of an employee, Steve, who was highly motivated, good at his work and had good decision making skills; he was chosen for an important production line function under a new boss, Jeff, who had just been promoted to a senior management position. Jeff wished to demonstrate that he was the boss and on top of the operation. He continuously supervised Steve, loaded him with high levels of paperwork and often changed his decisions. These actions resulted in dissatisfaction and resentment as well as negative performance appraisals. Steve resigned from the organisation within a year of his promotion.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Consumers visit spas more because of hedonic motives rather than for reasons that can be described as sensible, rational or strictly utilitarian. Whilst orthodox utilitarian perspectives are apt to describe such reasons as irrational, marketers realise that humans are not robotic in their responses and obtain pain and pleasure from a range of sources, many of which are subjective, differ from person to person and are not confined by the narrow bounds of mechanical rationality.

Marketers in the spa industry thus attempt to appeal to both rational and irrational needs of consumers by combining factors like cleanliness, economic prices, and competent staff with a range of choices, as well as options to customers to use green beauty products and massage oils. With environmental issues occupying top of mind among today’s customers, the feeling of doing a little bit to help the green cause provides some emotional satisfaction and possibly also assuages guilt that could be associated with engaging in costly self indulgence.

Spas, like other manifestations of the contemporary consumption society (for example Formula 1 racing) satisfy needs, which whilst not rational in the orthodox sense, are not stranger than those of customers seeking high fashion clothes or holidays in the Bermudas. Whilst pilloried by post modernists, they provide both customers and providers with a range of benefits and are here to stay.

References

Ariely, D, & Wertenbroch, K, (2002) Procrastination, Deadlines, and Performance: Self-Control by Precommitment, Psychological Science, 219-224.

Bagozzi, R.P., & Dholakia, U. (1999) Goal-setting and Goal-striving in Consumer Behaviour, Journal of Marketing 63 (October): 19-32.

Batra, R & Ahtola, O.T, (1990), Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Sources of Consumer Attitudes, Marketing Letters, 159-170.

Berry, C.J, (1994), The Idea of Luxury: A Conceptual and Historical Investigation, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bettman, J.R, (2005) Next Deal, Psychology and Marketing, 11, 5, 12 to 18

Blattberg, R.C., (2004), Winning Back the Customer, Journal of Marketing Research, 7, 2, 32 to 37

Consumer Behaviour, (2009), Xavier Institute of Management, Retrieved December 12, 2009 from www1.ximb.ac.in/users/fac/MNT/mnt.nsf/…/Cons%20Beh.ppt

Dahl, D.W., Honea, H, & Manchanda, R.V, (2003), The Nature of Self-Reported Guilt in Consumption Contexts, Marketing Letters, 159-171.

Deaton, A, & Muellbauer, J. (1980) Economics and Consumer Choice, New York: Cambridge University Press

Dhar, R., & Wertenbroch, K, (2000), Consumer Choice between Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods, Journal of Marketing Research 37 (February): 60–71.

Dowling, G, (2003), The Customer Loyalty Continuum. Customer Loyalty and Customer Loyalty Programmes, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 9, 3, 45 to 74

Dubois, B., Laurent, G., & Czellar, S, (2004) “Segmentation Based on Ambivalent Attitudes: The Case of Consumer Attitudes toward Luxury,” Working Paper, HEC, France.

Firat, A. F, (1991), The Consumer in Postmodernity, Advances in Consumer Research, 18:

Foxall, G, (2009), Interpreting Consumer Choice, Routledge

Hsee, K.C & Rottenstreich, Y, (2004), Music, Pandas, and Muggers: On the Affective Psychology of Value, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 133 (March): 23-30.

Kaplan, B, (2006), Delivering Customer Service in a Time of Crisis. CRM Today,

Khan, U. and Dhar, R. (2005) “Licensing Effect in Consumer Choice,” Working Paper, Yale University Amaldoss, W, & Jain, S, (2005), Pricing Of Conspicuous Goods: A Competitive Analysis of Social Effects, Journal of Marketing Research, 42, (February), 30–42.

O’Cass, A & McEwen, H, (2004), Exploring Consumer Status and Conspicuous Consumption, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 4(1): 25–39.

O’Shaughnessy J, & O’Shaughnessy, N, (2007), The undermining of beliefs in the autonomy and rationality of consumers, Routledge

Pine, B., J, (1999), The Experience Economy. Cambridge. Harvard Business School Press

Register, J, (2009), Spa evolution, a brief history of spas, about.com, Retrieved December 12, 2009 from spas.about.com/cs/spaarticles/l/aa101902.htm

Spa Sentiment Research Report 2009, (2009), Coyle Hospitality Group & WTS International, Retrieved December 12, 2009 from www.coylehospitality.com/Press/latest-spa-consumer-trends.asp

O’Cass, A & McEwen, H, (2004), Exploring Consumer Status and Conspicuous Consumption, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 4(1): 25–39.

Trigg, A, (2001), Veblen, Bourdieu, and Conspicuous Consumption, Journal of Economic Issues, 35 (1): 99–115.

More From This Category

Cross-Cultural Communication Challenges: Dealing with China

This report aims to investigate, analyse and assess the various cross-cultural difficulties and challenges that can arise in Alliance Boots’ proposed project for the development of a joint venture in China for the production of alternative medicines.

The report is sequentially structured and deals with various dimensions of national cultures, the differences between the cultures of different nations, and the ways in which such cultural differences can result in diverse types of problems and challenges in the course of interaction between employees of different cultures in multicultural workplaces.

The report specifically deals with the various cross-cultural communication problems that can arise during the implementation of organisation’s project in China, as the diverse ethical and commercial challenges that may have to be faced and overcome by the organisation for the successful implementation of the project.

The report provides detailed suggestions and recommendations on the ways and means for overcoming diverse cross-cultural communication and other problems. It ends with a summative conclusion.

Cultural and Linguistic Challenges in International Business

MNCs have become exposed to various cross-cultural challenges, stemming from differences in the national cultures of their home and host locations and the linguistic diversity of their geographically dispersed operations. These corporations have adopted several types of strategies for managing these challenges, some of which have in turn resulted in the development of other problems.

0 Comments