The Use of History in the Field of Intelligence in the Backdrop of Major Epistemological Limitations to its use as a Learning Tool

Introduction & Overview

This essay aims to investigate and analyse the major epistemological limitations to the use of history as a learning tool and attempts to ascertain, in light of such limitations, its use in the field of intelligence.

The awareness of different ontological and epistemological understandings is critical for the estimation of the utility of specific disciplines in the area of learning (Iwasaki & Narita, 2008). Different disciplines have their own modes of representation and their expectations regarding the hearing of the author’s voice, either implicitly or explicitly, in the course of writing (Gaddis, 2004). Crabtree (1993) stated that the study of history is important because the person who controls the past can control the future. A person’s perspective of history shapes the ways in which he views the present and thus dictates the answers he provides for existing problems (Crabtree, 1993).

The publication of Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago in 1973, an extensive piece of historical research, revealed the cruelty and injustice of the Soviet system and showed that Lenin and Stalin actively and knowingly participated in the formation of this brutal institution (Crabtree, 1993). The publication of the Gulag Archipelago offered a different depiction of official history, resulted in people doubting the official history and, according to Crabtree (1993) contributed to the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

History, going by this example, very clearly affects learning and the course of events (Butterfield, 1965). Historical research has, however, been constantly exposed to external bias on account of its role in the development of social and political consensus through the definition of collective identities, loyalties and exclusions, ever since the 19th century, when it was incorporated as an essential element of school curricula in European countries, aimed at raising soldiers and patriots (Butterfield, 1965).

Recent decades have witnessed the academic study of intelligence, more so in the United Kingdom and the United States (Hedley, 2005). Efforts to establish the history of intelligence have varied greatly, ranging from sensational media storage to patiently written and erudite works of serious historians (Hedley, 2005). The history of intelligence has of late become extremely important in the wake of terrorist attacks across the world, the conflicts in Iran and Afghanistan and the threats posed by nuclear powered irresponsible nations like Pakistan and North Korea (Hedley, 2005).

This short study discusses the epistemological limitations of history and their impact on its use as a learning tool in the area of intelligence. The essay first takes up the investigation of the ways in which the development of historical study and writing has been taken up by various experts and the diverse influences of power and politics to which it has been subjected. It thereafter focuses upon the development of intellectual history in recent years and elaborates upon its progressive maturing into a subject of serious study in contemporary times.

The investigation and analysis reveal that the study of history in the area of intelligence has commenced in a serious manner in recent years, pursuant to the ending of the cold war and the decision by many governments to declassify secret military documents. Contemporary intelligence history does thus provide significant scope for learning, both for intelligence practitioners and policymakers.

Discussion and Analysis

History as a Learning Tool

It is the objective of historical research to trace historical events to their sources (Harnett et al., 2009). Historians have to demonstrate the ways in which historical situations developed from previously existing conditions and the ways in which events beyond human control and the actions of men changed previously existing circumstances into subsequent situations (Harnett et al., 2009). It is difficult to carry out such analytical retrospection because history, sooner or later, arrives at a point when methods of interpretation do not serve it any further (Neustadt & May, 1988). Historians can in such circumstances, do little more than establish the presence of a factor that resulted in certain circumstances (Neustadt & May, 1988). It is by and large common to speak of uniqueness or individuality to describe a factor that cannot be traced back to others (Tanaka, 1997).

Such reference to individuality does not result in any interpretation or explanation but on the other hand, requires readers to deal with the inexplicable datum of historical experience (Iggers, 1975). Historical research, as briefed mentioned earlier, is also exposed to significant external bias on account of the involvement of dominant political powers in its shaping and development (Iggers, 1975). This model of historical research, developed in Europe and extended across the world, escorted by tools of censorship and control, have resulted in several cases of repression and conflict whenever historians have deviated from the role imposed upon them (Gaddis, 2004). Marco Ferro (1986) provided a comprehensive overview of the diverse forms of political bias that have affected global history, from the Soviet Union to India and from Egypt to Iraq. Procacci (2005) expanded upon Ferro’s work and revealed that little had changed in 20 years.

The Japanese ministry of education approved, in 2005, a history textbook that downplayed Japanese war crimes during the Second World War, a decision that resulted in street demonstrations in South Korea and China and diplomatic conflict (Tanaka, 1997). History was again rewritten after the collapse of the Soviet Union between Russia and some of the adjacent European states when the latter expressed the opinion that the entry of the Russian Army at the closing stages of the Second World War was more in the nature of an occupation, rather than liberation from Nazi Germany (Procacci, 2005).

The Development of Intelligence History

Intelligence history has for long been a neglected historical discipline, unrecognised and marginalised by more popular sub-disciplines (Andrew, 1988). It has, in fact, been described as the missing dimension in historical research as evident from its lack of presence in modern governmental literature (Andrew, 1988). Few serious historians have been willing to fill this significant deficit because the intelligence community, not just in the UK but in most western nations, including the USA and Russia, has remained invisible and an entity about which questions have not been asked (Andrew, 1988).

Work for the intelligence services has for many decades been cloaked in secrecy, with its operatives, at various levels being shadowing figures, known only to insiders (Liakos, 2009). Governments, across the divide of the cold war or the Maginot line, have constantly refused to even acknowledge the existence of such agencies (Hedley, 2005). Its functioning has, in fact, been compared to marital sex, which obviously goes on but is not spoken or written about (Hedley, 2005).

With historical researchers being deprived of various documents and facts about intelligence services in order to prevent public debate on the subject, the work of intelligence operatives has been discussed, deliberated and researched by investigative journalists, who have, more often than not worked upon internal leads from government sources and have made substantial use of their fertile imaginations to develop readable quasi-historical accounts (Robertson, 1987). Such writing has often been termed as “airport bookstall” history and has not really been taken seriously by students as well as decision-makers (Robertson, 1987).

Intelligence history, however, started becoming more organised and genuine from the 1980s on account of revelations about the CIA’s doubtful and possibly unlawful activities, including the surveillance and shadowing of domestic non-conformists and dissenters and the clandestine subversion of foreign governments (Hedley, 2005). The discipline of intelligence studies has thereafter improved substantially in terms of student and doctoral research, which in turn has resulted in the steady production of diverse, well studied and indeed impressive research literature (Hedley, 2005). The discipline has, in fact, over the past two decades, become associated with high-level scholarship, which has interestingly coincided with increasing public awareness about intelligence (Moran, 2011). The closure of the cold war and the entry of various members of the Soviet Union into the democratic polity and the market economy have led to positive anticipation about geopolitical tranquillity and in a greater focus on transparency, lucidity and answerability in intelligence research (Moran, 2011).

This period has happily been accompanied by the gradual reduction and deconstruction of various taboos about intelligence research and to the progressive declassification of substantial amounts of documentary evidence (Davies, 2001). Such declassification has resulted in a veritable bonanza of information for researchers of intelligence history and has helped in proving or disproving earlier historical narratives on intelligence history (Davies, 2001). Aldrich (2004) stated that intelligence historiography has in recent decades been significantly strengthened by interdisciplinary synergies on account of the involvement of experts in political science, sociology and law, which has resulted in the development of a distinctive and unambiguous research cluster. Some historians have adopted the bottom-up strategy for writing intelligence history, purposely travelling beyond the area of high politics to search and discover the personal and private experiences of intelligence operatives in intimate detail, including political orientation, social class and sexuality (Aldrich, 2004). Such historical research has dealt with the unfeeling and pitiless facets of a secret state and has overturned conventional and accepted views by showing both the western and east European intelligence services to be corrupt and contentious of the law and the state (Liakos, 2009). It must, however, also be recognised that a substantial proportion of the existing literature has been influenced by parochialism and the view that everything that occurs in intelligence work is for the best of all the worlds (Liakos, 2009).

There is little doubt of the significant use of history, despite the presence of bias and political manipulation, in the expansion of learning (Moran, 2011). Research into intelligence activities on both sides of the iron curtain have revealed stunning information on the web of espionage that was cast over various countries (Moran, 2011). It has, for example, been revealed that a hundred Britain’s worked, knowingly and unknowingly, as agents of the Soviet Union (Moran, 2011).

Advocates of the benefits of history claimed that it can be used for lessons and for taking decisions both in current and future times (Davies, 2001). It has, for example, be suggested that familiarity of decision-makers before the commencement of the Iraq war, with unsuccessful British attempts to assess the nuclear capabilities and arsenal of the Soviet Union, would have resulted in a greater understanding of the difficulty in estimating stocks of weapons of mass destruction (Davies, 2001).

It can, in conclusion, be seen that whilst history is limited by the information available to researchers and the need to comply to some extent with existing political powers, the area of intelligence history is becoming increasingly well researched and reliable (Moran, 2011). Intelligence historians are not really enquiring into long past events about which information is sparse (Moran, 2011). The constant declassification of intelligence documents by various countries that were vehemently opposed to each other in the past but are now members of the democratic polity and the market economy is helping historical researchers to develop multifaceted information that provides details about various facets of historical intelligence events (Aldrich, 2004). There is little doubt that intelligence history, as is being developed at present, can be extremely useful as a learning tool, both for intelligence practitioners and for decision-makers (Aldrich, 2004).

Conclusions and Recommendations

The investigation conducted for the purpose of this essay reveals a number of interesting conclusions. This essay aimed to examine the epistemological constraints to the use of history for learning and thus aimed to examine its utility in the area of intelligence. It becomes evident that history, as written until now, has been subjected to various individual interpretations, as well as state and political influences. Very few historians have been able to withstand personal and external biases to develop totally impartial narratives. The discipline, however, does provide immense data for learning, allowing readers, teachers and students to form their own opinions from the study of different narratives on specific subjects and use them for action in the present day.

The field of intellectual history has, however, developed somewhat differently on account of the lack of availability of information on intelligence operations carried out by different nations. Such unavailability of actual information has resulted in the development of a substantial genre of quasi-historical and significantly fictionalised narratives of intelligence history by people in the media and self-styled intelligence historians. Whilst the overwhelming majority of such information lacks authenticity and credibility and is thus of little use for learning, the situation has changed in recent decades, especially after the deconstruction of the Soviet Union and the dilution of the cold war.

Many governments are actively declassifying their intelligence records in a phased manner, allowing intelligence historians to develop fairly authentic and credible historical narratives that can be of significant use to readers, academics and students. Such historical narratives are being developed with the rigour required of academic research and with the help of authentic intelligence information. Contemporary intelligence history is thus becoming significantly authentic in its narration of events and use as a learning tool for assessing the past and planning for the future.

References

Azmi, M., 1978, Studies in early Hadith Literature, Indianapolis: American trust Publications.

Berg, H., 2000, The development of exegesis in early Islam: the authenticity of Muslim literature from the formative period, London: Routledge.

Falahi, G.N., 2010, “Development of Early Hadith Literature, Principal of Collection And Genre of Authenticity”, Available at: http://muqith.files.wordpress.com/2010/10/development-of-hadith.pdf (accessed April 27, 2014).

Gilchrist, J., 1986, Muhammad and the Religion of Islam, Available at: answering-islam.org/Gilchrist/Vol1/0.html (accessed April 27, 2014).

Hallaq, W. B., 1999, “The Authenticity of Prophetic Ḥadîth: A Pseudo-Problem”, Studia Islamica, No (89): pp. 75–90.

Jonathan, A., & Brown, C., 2004, “Criticism of the Proto-Hadith Canon: Al-daraqutni’s Adjustment of the Sahihayn”, Journal of Islamic Studies, Vol. 15, No (1): pp. 1-37.

Juynboll, G. H. A., 2007, Encyclopedia of Canonical Hadith, Leiden: Brill.

Juynboll, G.H.A., 1983, Muslim Tradition, UK: Cambridge.

Lucas, S., 2004, Constructive Critics, Hadith Literature, and the Articulation of Sunni Islam, Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers.

Lucas, S., 2002, The Arts of Hadith Compilation and Criticism, University of Chicago.

Motzki, H., 1991, The Musnnaf of Abdl al-Razzaq al-San’ani as a source of authentic a Hadith of the first century”, Journal of near Eastern Studies, Vol. 50: pp. 1-21.

Meherally, A., 2011, “Myths and Realities of Hadith: A Critical Study”, Available at: http://www.mostmerciful.com/hadith-book1.pdf (accessed April 27, 2014).

Milby, A.K., 2008, “The Making of an Image: The Narrative Form of Ibn Ishaq’s Sirat Rasul Allah”, Religious Studies Theses, Available at: http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=rs_theses (accessed April 27, 2014).

Musa, A. Y., 2008, Hadith as Scripture: Discussions on The Authority Of Prophetic Traditions in Islam, New York: Palgrave.

Robinson, C. F., 2003, Islamic Historiography, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Scott, C. L., 2004, Constructive Critics, Ḥadīth Literature, and the Articulation of Sunnī Islam, pg. 106, Leiden: Brill Publishers.

Shafi, M., 2009, “The HADITH – How it was Collected and Compiled”, Available at: http://www.daralislam.org/portals/0/Publications/TheHADITHHowitwasCollectedandCompiled.pdf (accessed April 27, 2014).

Warner, B., 2006, The Political Traditions of Mohammed: The Hadith for the Unbelievers, UK: CSPI Publishing.

More From This Category

Globalisation Challenges

Globalisation is the tendency of the public and economies to move towards greater economic, cultural, political, and technological interdependence. It is a phenomenon that is characterised by denationalisation, (the lessening of relevance of national boundaries) and is different from internationalisation, (entities cooperating across national boundaries). The greater interdependence caused by globalisation is resulting in an increasingly freer flow of goods, services, money, people, and ideas across national borders.

Does Capital Structure Matter

The capital structure of a modern corporation is, at its rudimentary level, determined by the organisational need for long-term funds and its satisfaction through two specific long-term capital sources, i.e. shareholder-provided equity and long-term debt from diverse external agencies (Damodaran, 2004). These sources, with specific regard to joint stock companies, retain their identity but assume different shapes.

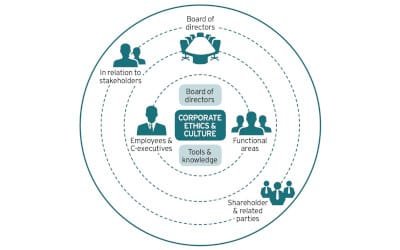

Ethical and Governance Challenges for Businesses and Professionals

It is the duty of business organisations to refrain from engaging in actions that are harmful to their various stakeholders, including the society and the environment and furthermore work purposefully towards benefiting them.

0 Comments