Water Management in South Asia: A Problem Management Approach

Introduction & Overview

“Increased water scarcity is fundamentally a problem of management”. This essay engages in the discussion of this statement with particular regard to the nexus between water and food in India and South Asia.

Much of the contemporary debate and discussion about water in South Asia, with particular regard to the shared rivers of the region, is becoming increasingly antagonistic on account of its implications for national food security (Biswas, 2009). Renewable water resources in South Asia have fallen rapidly since the 1960s on a per capita basis (Biswas, 2009). India approached the water stress mark in the early years of 2000, whilst Pakistan hit it slightly earlier (Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses (IDSA), 2010). Groundwater is going down rapidly in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and the policymakers and governments of these countries have few solutions for enhancing its supply (Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses (IDSA), 2010).

It needs to be appreciated that South Asia faces some of the greatest population pressure on land in the world (Price et al., 2014). The region’s population is expected to grow by 32%, from 1.68 billion in 2010 to 2.22 billion in 2040 (Price et al., 2014). This sustained growth in population has resulted in tremendous stress on natural ecosystems and led to the degradation of wetland, rivers, aquifers and soil (Shah & Lele, 2011). With the human population of South Asia has increased three times since 1950, its per capita water availability has gone down to 20% of what it was 60 years ago (Shah & Lele, 2011). The corresponding reduction of availability of arable land on a per capita basis has very obviously resulted in very significant dangers and risk with regard to food in the short and medium-term (Biswas, 2009).

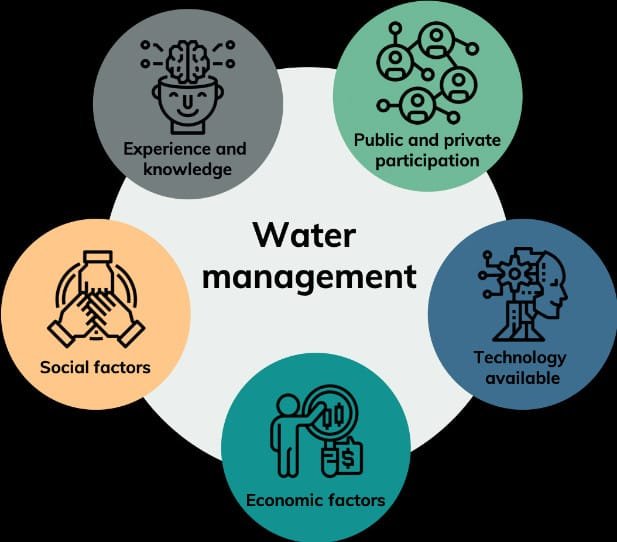

Various water management experts have, however, pointed out that much of the region’s current water difficulties and associated food production difficulties stem from short-sighted policies, unnecessary disputes between nations, and poor quality of management and implementation (Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses (IDSA), 2010). They have stated that various steps can be adopted by national governments and water management bodies to bring about significant improvements, both in the availability of water and its use for food production (Price et al., 2014). This short paper studies and analyses various inadequacies and difficulties in the management of water resources in India and South Asia, as well as the measures that can be taken to enhance the situation.

Discussion and Analysis

Water management across South Asia is viewed through the perspectives of agriculture and the requirements of farmer (Khandekar, 2014).

With approximately 90% of the water in the region being utilised for agriculture, the relationship between food and water is considered to be paramount in all South Asian countries (Khandekar, 2014). The links between energy, food and water are most clearly identified in India, where the government provides free or subsidised electricity to farmers to pump water for agriculture from canals, rivers and other freshwater bodies (Shah & Lele, 2011).

Agricultural activities in South Asia consume approximately 71% of available freshwater, either through irrigated or rain-fed systems (Foster & Van Steenbergen, 2011). Experts state that approximately 50% of this water can be used more productively through the elimination of inefficiencies in production and irrigation (Foster & Van Steenbergen, 2011). Irrigation efficiencies have continued to remain low in South Asia on account of governmental persistence with energy subsidies (Foster & Van Steenbergen, 2011). Efficiencies in agricultural water management in South Asia increased by only 1% per year during the last two decades; significantly lesser than the efficiency increases achieved by the developed countries (Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) of the World Bank, 2010). Research has revealed that approximately 40% of food production in India is wasted every year (Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) of the World Bank, 2010). Investments in agricultural and water research have, despite these inefficiencies, reduced significantly over the course of the last few decades and national and state governments have not taken initiatives to enhance productivity and efficiency (Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) of the World Bank, 2010).

The global debate about water scarcity is being driven primarily on account of its relationship with food (Kumar et al., 2012). Whilst scarcity of water availability is expected to be a limiting factor in industrial production, the real threat stems from the impact of water scarcity on food production and the inability of agricultural systems to provide enough food to satisfy the needs of steadily increasing population (Kumar et al., 2012). Concerns about water security are global; South Asia is however unique in this regard because of its enormous opportunities and some very real threats (Allan, 2011). It needs to be noted in this regard that whilst lifestyle and consumption trends are changing rapidly in fast industrialising India, South Asia is home to a significantly larger proportion of the world’s undernourished people than its population warrants (Price et al., 2014). Continuing enhancements in total population, along with greater urbanisation and prosperity are likely to result in greater demand for food, changes in dietary demands and enhancement in demand for water-intensive products like dairy and meat (Price et al., 2014).

Policymakers, governments and private and public sector organisations need to work in conjunction with each other to bring about required enhancements in water and related food-management efficiency (Shah, 2009). It is firstly important to put relevant facts and information in the public domain (Shah, 2009). Governments have to acknowledge that food security in South Asia is likely to worsen without enhanced water management, reduction in use of water for agriculture and improvement in agricultural productivity (Biswas, 2009). Food prices will continue to fluctuate on account of demand and supply-side reasons including increasing weather fluctuations (Obeng, 2009). Poverty will worsen across India and South Asia if indiscriminate mining and consumption of strategic groundwater reserves continue unabated (Biswas, 2009; Cronin et al., 2014). The destruction of aquatic ecosystems on account of failures to understand their true value in stabilisation and storage is likely to enhance problems with water scarcity (Obeng, 2009; Cronin et al., 2014). It must be understood that governmental policies and rampant private greed has resulted in the mining of non renewable resources and the giving away of water for free, often through blanket subsidies (Obeng, 2009; Cronin et al., 2014).

Several experts, especially those from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have however stated that the food demands of India and other South Asian countries can be satisfied in several ways through the adoption of appropriate policies and mechanisms (Asian Development Bank, 2015). The ADB has stated that investments should be made to enhance production in rain-fed agriculture through improved management of (1) soil moisture, (2) soil fertility, and (3) supplemental irrigation with small amounts of water storage (Asian Development Bank, 2015). It is also important to simultaneously take steps for reversal of land degradation (Schneider, 2013). Investments will have to be made in irrigation in the area of enhancement in water supplies through innovative methods, like the use of wastewater, development of new surface water storage facilities and innovations in system management (Schneider, 2013). Steps will also have to be taken to enhance water productivity in irrigated areas (Schneider, 2013).

National governments, along with the farming sector must work together to ensure productive consumption of water in agriculture (Allan, 2011). Efforts should be made to maximise the production of food, fibre and fuel with minimal water consumption (Obeng, 2009). Several agricultural water diversions in irrigation are presently considered to be inefficient (Obeng, 2009). Efforts should be made to use water that is not consumed or returned downstream in other productive activities, thereby enhancing the total efficiency of water management (Price et al., 2014).

Conclusions and Recommendations

This paper aimed to examine the role of inadequate management in increasing water scarcity, with particular regard to the nexus between water and food in India and South Asia.

The study conducted for this purpose revealed that water scarcity in the region have enhanced significantly in recent times, with both India and Pakistan hitting the water stress mark. Whilst pressure on water availability has of course been caused by the enhancement in the population of this region, the scarcity in water resources has actually developed on account of extremely poor management of water resources, both through poorly planned irrigation and through indiscriminate consumption of strategic groundwater resources, particularly the destruction of aquifers and ecosystems. National governments have constantly subsidised water and energy consumption for agricultural purposes through wholesale subsidies without making corresponding efforts to manage both renewable and non renewable water sources.

Water scarcity, which is bound to increase in future if corrective measures are not taken, will threaten the region’s capacity to produce adequate food at economic prices to satisfy the needs of its growing population. Experts, however state that several measures can be taken to ensure renewal of groundwater resources and improvement in efficiency of water management for both agricultural and non agricultural purposes. It is important for national governments, policymakers, government departments, the agricultural community and society at large to recognise the implications of the current water crisis and take positive and carefully thought-out measures to correct the situation.

References

Allan, T., (2011), Virtual Water: Tackling the Threat to Our Planet’s Most Precious Resource, London: I. B. Tauris.

Asian Development Bank, (2015), “Water-Food-Energy Nexus: At Work in South Asia”, Available at: http://www.adb.org/features/water-food-energy-nexus-work-south-asia (accessed February 07, 2015).

Biswas, A.K., (2009), “Water management: some personal reflections”, Water International, 34, (4): 402-408.

Cronin, A.A., Prakash, A., Priya, S., & Coates, S., (2014), “Water in India: situation and prospects”, Water Policy, 16: 425–441.

Foster, S., & Van Steenbergen, F., (2011), “Conjunctive use of groundwater: a ‘lost opportunity for water management in the developing world?”, Hydrogeology Journal, 19(5): 959–962.

Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) of the World Bank, (2010), Water and Development: An Evaluation of World Bank Support, 1997 – 2007, Volume 1, Washington, DC: the World Bank.

Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses (IDSA), (2010), Water Security for India: The External Dynamics, New Delhi: IDSA.

Khandekar, N., (2014), “South Asia slow to act on water threats”, Climate News Network, Available at: http://www.climatenewsnetwork.net/south-asia-slow-to-act-on-water-threats/ (accessed February 07, 2015).

Kumar, M.D., Sivamohan, M.V.K., & Narayanamoorthy, A., (2012), “The food security challenge of the food-land-water nexus in India”, Food Security, 4:539–556.

Obeng, L., (2009), “Water Security – Food Security – Climate Change Nexus”, Food Security 2009: Achieving long-term solutions, Session Six: Use of Resources, Available at: http://www.gwp.org/Global/Activities/News/091116_ChathamHouse.pdf (accessed February 07, 2015).

Price, G., Alam, R., Hasan, S., Humayun, F., Kabir, M.H., Karki, C.S., Mittra, S., Saad, T., Saleem, M., Saran, S., Shakya, P.R., Snow, C., & Tuladhar, S., (2014), Attitudes to Water in South Asia, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, London: Chatham House.

Schneider, K., (2013), “Breaking India’s Cycle of Waste and Risk”, Available at: http://www.circleofblue.org/waternews/2013/world/to-grid-or-not-to-grid-breaking-indias-cycle-of-waste-and-risk/ (accessed February 07, 2015).

Shah, T., & Lele, U., (2011), “Climate Change, Food and Water Security in South Asia: Critical Issues and Cooperative Strategies in an Age of Increased Risk and Uncertainty”, A Global Water Partnership (GWP) and International Water Management Institute (IWMI) Workshop, Colombo: Sri Lanka.

Shah, T., (2009), Taming the Anarchy: Groundwater Governance in South Asia, Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

More From This Category

Globalisation Challenges

Globalisation is the tendency of the public and economies to move towards greater economic, cultural, political, and technological interdependence. It is a phenomenon that is characterised by denationalisation, (the lessening of relevance of national boundaries) and is different from internationalisation, (entities cooperating across national boundaries). The greater interdependence caused by globalisation is resulting in an increasingly freer flow of goods, services, money, people, and ideas across national borders.

Does Capital Structure Matter

The capital structure of a modern corporation is, at its rudimentary level, determined by the organisational need for long-term funds and its satisfaction through two specific long-term capital sources, i.e. shareholder-provided equity and long-term debt from diverse external agencies (Damodaran, 2004). These sources, with specific regard to joint stock companies, retain their identity but assume different shapes.

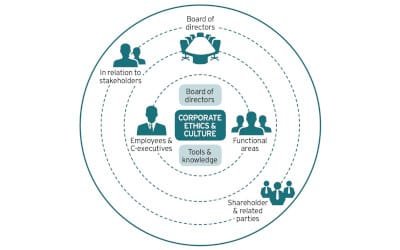

Ethical and Governance Challenges for Businesses and Professionals

It is the duty of business organisations to refrain from engaging in actions that are harmful to their various stakeholders, including the society and the environment and furthermore work purposefully towards benefiting them.

0 Comments